Expensive Shit, Soho Theatre

Friday 7th April 2017

It’s hot. Real hot. And you’re dancing, just lost in music. You’re at the legendary Shrine nightclub in Lagos, where Afrobeat star Fela Kuti is king. It’s 1994. And it’s hot. Sweat is just pouring off you, no longer in little trickles but soaking through your clothes. And still you dance. As the beat pounds along, you can hear Fela intone: “Men are born; kings are made”, then something about “one nation, indivisible”, before he says, “War has never been the answer — long live Nigeria! Viva Africa!” It sounds like glory. Surely this is heaven on earth.

The next day, in Adura Onashile’s 65-minute play, Expensive Shit, the teenage Tolu spends most of her time in the club’s toilet with her three mates, practising the dance routines that they will perform when the charismatic Fela plays. They are part of his following at Kalakuta, the musician’s sanctuary for the dispossessed, from where he preaches his gospel of anti-corruption, anti-colonialism and anti-capitalism. He is the man, and the girls want to catch his eye. If they succeed, who knows? Maybe he will invite them to dance or sing in his band. Or maybe they will become one of his wives. They live in hope.

Fast-forward to Glasgow, Scotland, in 2013. Tolu is once again in a toilet, but this time she is no longer a teenager perfecting her dance moves; she is the toilet attendant. It’s a nightclub. And conditions are not good. Although she is Queen of the Toilets, the shit watcher, the night woman, she is unpaid and depends on tips from customers, to whom she provides cosmetics and perfume. At the same time, she has to do what the management tell her, so she encourages the young women to apply their lipstick in front of a two-way mirror, or leave their cubicle doors open, or drink from water bottles laced with a date-rape drug. It’s a grim contrast with her youthful hopes.

First seen with a mostly different cast in Edinburgh last year, now transferred to Soho Theatre, Onashile’s play flips between the two time zones, and is a powerful account of female oppression — she shows us that the two toilets are not really a world apart. But although Tolu does the most distasteful things, she is not indifferent to the abused women at the nightclub. And she’s conscious that her teenage idealism has soured into adult sorrow. We watch as she experiences a crisis of conscience, but then we find out that life in Kalakuta was not as rosy as it first appears. Even revolutionaries can be sexist, cruel and abusive. It’s an acute point, and strongly realized on stage.

Like Atiha Sen Gupta’s Counting Stars, which is also set in a pair of toilets, Onashile’s play suggests various issues beyond what we see on stage. When she gets to Glasgow, Tolu is a migrant from Nigeria, so has probably been exploited along the way. Clearly, she is working illegally in the sense that her employers are not even paying her the minimum wage, and she depends on the odd pound thrown her way by the nightclub’s customers. Apart from one scene when she makes human contact with one such, there is little sense of solidarity between the women, in contrast to the moments set in Lagos, where the young girls are both fiercely individualistic and attempt to support each other collectively: “We all get chance to shine,” says one of them. By contrast, Glasgow is a lonely place for Tolu.

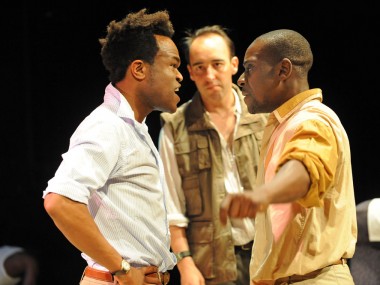

Expensive Shit is quite a slender play, with little plot development or character depth, but it does make a vivid impression. Onashile directs her new four-woman cast — Kiza Deen (Tolu), Veronica Lewis, Jamie Marie Leary and Maria Yarjah (who each play two women, one for each time zone) — in a series of setpieces that include the exhilarating Nigerian zombie dance and the climactic shout of defiance from the Glasgow lasses. Choreographer Lucy Wild delivers the goods on designer Karen Tennent’s white-tile set, whose frames suggest the twin themes of voyeurism and exhibitionism. But there is a streak of melancholy and disillusionment, as well as anger at pervasive everyday sexism, that perfectly balances the pleasures of Afrobeat music and its ability to make the world disappear — if only for a while.

This review first appeared on The Arts Desk