Go Bang Your Tambourine, Finborough Theatre

Thursday 8th August 2019

Theatre legends die hard. Playwright Philip King, who passed away in 1979, was once hailed as the monarch of the farceurs, and his best-know play, See How They Run (1944), features the immortal line: “Sergeant, arrest most of these vicars!”. Like so many legendary lines, this one is not in original text, which actually says: “Sergeant, arrest most of these people!” But never mind, the remarkable thing about his 1970 drama, Go Bang Your Tambourine, is that it has never been seen in London, until now that is, thanks to the advocacy of Two’s Company and this fringe venue, both of which specialize in rediscovering forgotten classics.

The play’s title does take some forgiving, but its ingredients are familiar: set in a Lancashire two-up, two-down house, this is a family drama in a place vaguely reminiscent of Coronation Street. Nineteen-year-old David Armstrong — a member of the Sally Army who is training to be a cornet player — lives on his own, having just lost his mother. He is a naïve soul, and lonely. When he advertises for a lodger, he is pleased that miniskirted Bess, an older local barmaid, responds and decides to move in. So far, so odd couple: he is very repressed and she is ebullient. But what will Major Webber, the female head of the god squad, think of this morally lax domestic arrangement?

This mix of innocence and experience — which gets a shot of emotional intensity when Tom, David’s long-estranged father pays an unexpected visit and is visibly attracted to Bess — is great material for an uproarious farce. You can imagine unexpected entrances, dropped trousers and a young woman in a negligee. What misunderstandings there could be; what larks; what laughs. What a potential avalanche of double meanings. But no such luck. This time, King decided to subvert his reputation, and to treat this situation seriously — and, sadly, this was not a good idea.

For a start, all of the characters are based on stereotypes: David is the nerdish mummy’s boy, Bess is the tart with a heart, the Major a prudish spinster and Tom a Lothario. Great for a farce, not so good for a serious play. And King’s clumsy attempts to deepen his characters by giving them shades of complexity don’t really work. To be fair, he does show how both Bess and the Major act as mother substitutes to the bereaved David, and the introduction of Tom as his son’s rival for Bess’s affections does give the play a hint of oedipal tension. In fact, the best scenes are the initial exchanges between David and Bess, which are excruciatingly awkward, and the later conflict between father and son, when their mutual hatred is clearly articulated.

The competition between the two men, the father sexually experienced and his son a virgin, for the single woman is brutal and intense. However, there is something not a little disturbing in King’s portrait of the openly sexist Tom, while his depiction of Bess, who can’t seem to decide whether to be good or not, and who is attracted to Tom despite her correct perception that he’s a male chauvinist pig, is definitely dated. The piece’s sexual politics manage to be of the 1970s, without being critical of the times. If anything, they feel reactionary. Maybe King should have asked for advice from some women.

So a story that starts as quite a tender image of an odd relationship between a needy young man and a boisterously confident slightly older woman, eventually becomes an unpleasant representation of masculine groping and manipulation. Tom’s attack on his newly deceased wife, and David’s mother, is that five years previously she ruined their marriage because of her religious beliefs, yet clearly — judging by his current behaviour (which the playwright seems to endorse) — he is unable to remain faithful to anyone. As well as being a kind of study of family psychology, the play also shows how Christianity results in delusions: David firmly believes that Bess was sent to him by God, a suggestion that the Major, his spiritual adviser, flatly rejects.

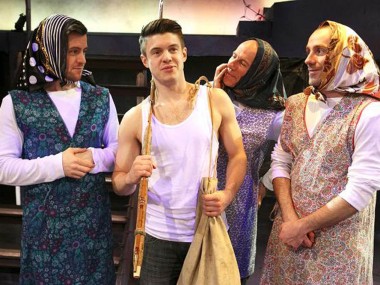

The Two’s Company team, director Tricia Thorns and designer Alex Marker, whose meticulous set is a quiet joy, do their best with unpromising material. The production’s strong point is its casting: Sebastian Calver and Mia Austen make a nice contrast as the gawky David and the feisty Yorkshirewoman Bess, while John Sackville is great as the creepy slimeball Tom. Patience Tomlinson’s maternal Major is pitch-perfect. However, the decision to have two intervals, and the several episodes when the energy sags, make this a long-winded evening of almost three hours. Since King has little to say that is really interesting about religion, sex or friendship, that is simply too much. By the end, I longed for some hectic tambourine banging!

This review first appeared on The Arts Desk