Grief Is the Thing with Feathers, Barbican Theatre

Thursday 28th March 2019

Wow, what a collection of talent: this show stars Peaky Blinder Cillian Murphy, and Enda Walsh’s adaptation, Grief Is the Thing with Feathers, is based on Max Porter’s award-winning novel of the same name. From the first this seems like a good fit: Walsh, as his 1999 classic, Misterman, shows, is deeply at home with loss, longing and torment, and this description could equally apply to Porter’s 2015 book, whose stage version was first seen in Galway about a year ago, and is now visiting the Barbican. Readers will remember the set up: in a London flat, a father and two young boys face the sadness of their mother’s sudden death. During this time of loss, they are visited by Crow — bereavement counsellor, tricksy character and bizarre babysitter.

Dad (Murphy) is an academic, an expert on Ted Hughes, so there’s an immediate link with this poet laureate’s 1970 collection, Crow, as well as to his much later Birthday Letters, a response to his wife Sylvia Plath’s suicide, another moment of acute loss. These poems are a way of using symbols to deal with very deep feelings, creating a mental and emotional space where the world of nature embraces, and perhaps soothes, human despair. Hughes’s Crow is an elemental force, strong smelling and strong minded, violent and a real presence to be reckoned with. A creature of control. After the initial shock of his arrival, Crow says: “I won’t leave until you don’t need me any more.”

Numbed by grief, Dad and his Boys succumb to the bird’s residency. Walsh, who also directs this dazzling multi-media show, has not only adapted Porter’s story, but has also given it wings. Inspired by the literary experimentation of the original, Walsh has combined bravura acting — Murphy plays both Dad and Crow — with a battery of visual effects, some of which are powerfully effective. While chapter headings from the book are projected in huge scratched scribbles across this venue’s massive back wall, there are direct quotations from the novel and brief home-movie images of the dead Mum. Plus some audio memories. At times, it’s like a living graphic novel with Murphy dominating the stage.

As in Walsh’s Misterman, which also starred Murphy (a long-time Walsh collaborator), this is very much a one-man performance. Dressed in a black hooded garment, like a symbolic medieval figure of death, the actor goes foot-skipping across the stage on tip-toes, his voice veering between mic’d-up imperious commands and throaty whispers. One moment he’s a terror; next he’s giggling. Shape-changer. When he’s in full flight, puffed up and broadly gesticulating, he conveys an animal-world strangeness; when he satirises human attitudes, with a plummy upper-class voice, he’s funny. Yes, Murphy’s Crow is a phenomenal creation.

This adaptation takes the audience and shoves them into a kind of primal forest where you might catch your parents having sex, spend time with a feathered trickster or feel guilt at killing a fish when you were a kid. Avian sensuality and primitive feelings of disgust rub along with good advice, with art therapy sessions and family photographs. It’s like psychodrama. In this psychological landscape memories are embodied in household objects, children grow up and widowers eventually have to move on. Ashes have to be scattered, and make sure you don’t piss directly into the wind. Cue electric storms and letter showers.

Disappointingly, for anyone who is not already a fan, the effect of the multi-media spectacle is not as transformative as the hype promises. At times, the inventiveness of Porter’s words and the sheer hugeness of the staging bombards you into submission. For me, the best bits are the very quiet moments, when Murphy stands still and just talks quietly to the audience. Because, in the end, loss is just loss. An absence; an ache. It’s a feeling that really doesn’t really need wild bird-talk and massive video effects. This show is strong, but I sometimes feel that the dish has been over-egged, over-spiced and over-done.

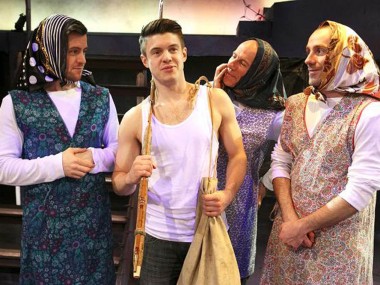

This co-production between Wayward and Complicite has an eyeball pleasing design by Jamie Vartan, moody music composed by Teho Teardo and video projections and slide shows by Will Duke. The rest of the cast — Hattie Morahan (briefly on film), with young actors David Evans, Leo Hart, Taighen O’Callaghan and Adam Pemberton taking turns as the two Boys — are good support for Murphy, who rules over the stage in this 85-minute piece. But, in the absence of a compelling plot, this is more of an illustration of a novel than a gut-grabbing, edge-of-the-seat drama. Talent only gets you so far.

This review first appeared on The Arts Desk