Hamlet, National Theatre

Friday 8th October 2010

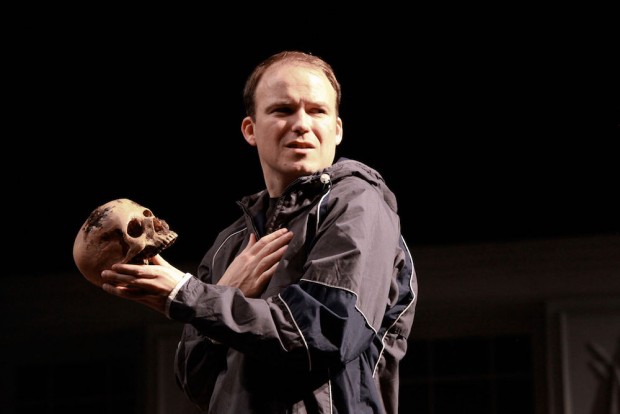

If, to Hamlet, Denmark is a prison, to us it is a surveillance state. In Nicholas Hytner’s new modern-dress production, the gloomy environment of autocratic power and control by spying is well conveyed, as uniformed soldiers, security police and miscellaneous spooks people the stage. It’s a spy’s mini-paradise. Amid this, and hard on the heals of other recent Hamlets played by Jude Law and David Tennant, comes Rory Kinnear’s youthful Prince of Denmark.

This Hamlet is a student type, who convincingly grapples with the situation he has been plunged into. His father’s ghost tells him that he has been murdered by Claudius, his own brother and young Hamlet’s uncle. Worse, Gertrude, Hamlet’s widowed mother, has rapidly married Claudius. Helped by his university chum Horatio, Hamlet throws off the distractions of women (Ophelia gets a raw deal) and tries to discover if what the ghost says is true. Sensing his danger, Claudius employs two other students, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, to keep an eye on Hamlet, and to see if he represents any danger to him. (Hence the spying!) Likewise, Polonius, the old councilor, is watching both Hamlet and on Laertes, his son and Ophelia’s brother.

In this production what is remarkable is how clearly Hytner articulates Shakespeare’s main preoccupations — the meaning of death, the imperative of revenge and the relationship between life and theatre — while at the same time creating a coherent picture of a contemporary society. This is a world of sofas, desks and office chairs, of guards and rules, where people are not particularly noble or larger-than-life: just ordinarily wary and keen to succeed.

In the title role, Kinnear offers a complex interpretation, which is hard to summarise briefly. He is sensitive to the changeable nature of the Prince, starting off numbed with shock and grief at his father’s death and his mother’s hasty remarriage, then passing through phrases when it is clear that he is playacting his madness, in order to gain time, and other scenes when he seems to have really lost it. Bright, sensitive, aware — this is Hamlet as an Oxbridge graduate.

Hytner’s direction throws Hamlet into an untidy bedroom, with an old chest of books, and allows him to smoke, even during the “To be or not to be” speech. He is also given a sense of humour to balance the mood swings and the bitter feelings of being sidetracked by a society that is meaner and more ambitious than suits his temperament. In a 24/7 society, he is distinctly a 9 to 5. Not only is the time out of joint, but he is unable to set it right.

In this contemporary dictatorship, which is more former-USSR than Scandinavian, planes hurtle overhead and Patrick Malahide’s Claudius is an unemotional politician whose eye is always on the main chance, while David Calder’s Polonius is a busybody who is sinister as well as buffoonish. He also doubles as the Gravedigger. As the ghost, and doubling as the Player King, James Laurenson brings a deep gravitas to his exceptionally well-spoken lines. Clare Higgins’s Gertrude, a neat mix of guilt and terror, contrasts nicely with Ruth Negga’s hip Ophelia, who not only loses her mind, but is hustled away by security guards in perhaps the most controversial moment of the play.

In general, Hytner’s reading is wonderful in its pace and clarity, and he emphasizes the background politics of the play. Against the backdrop of Vicki Mortimer’s clean-cut designs, the action never flags. The mime of the play scene is expertly choreographed, and the motivations of all the characters seem crystal clear. Definitely not for those who love ambiguity, this is a very enjoyable evening full of illumination. A Hamlet for today.

© Aleks Sierz