Haunted Child, Royal Court

Thursday 8th December 2011

Can you replace a wife with a doctrine? Under normal circumstances, the question would be absurd, but given that Joe Penhall’s new play, which opened tonight, is the latest of a crop that have explored belief, spirituality and religion, the conundrum is a very real one. And it’s here presented with unforgettable force in a compelling and stimulating play which itself seems guaranteed to haunt you.

In a terraced house in outer London live Douglas and Julie, who have been married for a while. They have a young son, Thomas, and are trying for another. Then Douglas goes missing. For weeks and weeks. When he eventually returns, he tells his shocked wife about a mysterious group that he’s joined. He has become a seeker after spirituality, following a guru and studying esoteric philosophy. It is a newfangled mix of transcendental meditation and the will to power. But what are the domestic implications of this weird doctrine?

At the heart of the play, as in Penhall’s other work — such as Landscape with Weapon in 2007 — is a fraught dialogue between a rampant idealist and a stoical pragmatist, with the addition that, in this case, their disturbed child is caught in the crossfire. Douglas not only articulates the common feeling that long relationships often become routine, but he also has some entertainingly bonkers ideas about how to change society through strict religious renunciation of all, and I mean all, the pleasures of the flesh. Look out for some glorious stage business with a metal bucket.

He also comes across as an overgrown, selfish little boy while Julie struggles with the day-to-day stresses of motherhood, a situation which was also a theme in Jumpy, April De Angelis’s recent play at this address. Douglas partly embodies a kind of nostalgia for the early days of a loving relationship, and partly he represents the idea of the troubled individual who finds solace in the warm embrace of a cult. What’s new and contemporary is the philosophy he espouses, an interesting melange of mystical religion and high-tech science.

Penhall — who has recently been busy on screenplays such as his excellent adaptation of The Road — writes with his trademark high energy, alternating between Douglas’s explanations of bizarre but provocative ideas and Julie’s more level-headed, and funny, one-liners. This facility makes Haunted Child such a thrilling mixture of the entertaining and the appalling; some moments are very humorous, others are deeply upsetting. Like the best drama, it appeals to both head and heart.

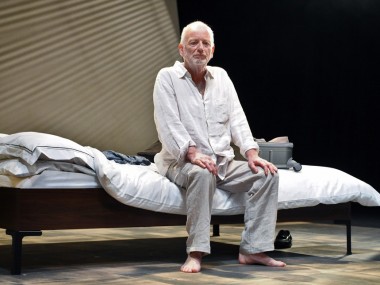

On Bunny Christie’s wintry set, Jeremy Herrin directs with acute attention to the shifting balance of power between the adults, and with aching sympathy for little Thomas. His cast is great: The Slap’s Sophie Okonedo plays Julie as a fragile, bewildered loner whose life and features are always about to collapse, but who can nevertheless deliver a sharp satirical rebuke, while Ben Daniels’s Douglas is a ragged loser, picking at the scabs of metaphysics with the enthusiasm of the terminally obsessed. And he grows into a mesmerising stage presence. Equally convincing are youngsters Jack Boulter and Jude Campbell, who share the role of Thomas. Not everyone will agree, but, with this text and these performances, this is one of the best new plays of the year. Just don’t expect it to be a seasonal haunting — it’s much more metaphoric than that…

This review first appeared on The Arts Desk