Here We Go, National Theatre

Saturday 19th December 2015

I’m watching this, the latest play by Britain’s greatest playwright, on the last night of its rather short run. Why? Is it because I was too busy on the week of its opening, or is it because I chanced to read some of its poorest reviews, or is it because of its subject matter? All of the above, probably, but I’m glad that I finally managed to catch it before it closed because it’s one of the best things I have seen all year. And one of those unusual shows that not only really affect the audience, but also split it right down the middle. And that’s what I call a great piece of theatre.

Billed as “a short play about death”, Caryl Churchill’s Here We Go is a 45-minute play composed of three sections. It begins with a funeral. Or rather with the awkward social interactions at a drinks party or wake immediately following the funeral. A diverse group of people share their memories and thoughts about the dead person, sketching out what he was like, what he liked and who liked him. But, as in similarly fragmentary works, such as Martin Crimp’s seminal Attempts on Her Life, the overall impression is that no one really knows, deep down, what the departed man was like. He seems to be, is some essential way, unknowable. Just like death.

This beginning is written as an open text, with none of the lines given to any specific, named character, so just a series of fragments, torn pieces of dialogue that float above the casual meeting of black-suited individuals in what could at any moment turn into a comedy of manners, of embarrassed social interaction. The dead man was an anarchist, or maybe just a sexual libertarian, with an “extraordinary mind” that encompassed both literature and science, a heavy drinker and a quarrelsome friend. The chit-chat of memories and opinions continues until each character addresses the audience, at some random point, with that most personal of information: the date and cause and circumstances of their own death.

In the second section, a half-naked man, played by Patrick Godfrey, explains in a rapid monologue, slightly reminiscent of Samuel Beckett, that he is dead. An everyman figure, he is the subjective essence of the dead man from the first section. He finds himself amid the teeming hoards of the other already dead, and it feels to him like “it’s worse than the tube at rush hour”. Various images from myth and poetry occur to him, from biblical goats and sheep to Charon and Cerberus, and these float through his consciousness. He wonders what the afterlife will bring, and yearns to have another life on earth, especially if he can “do it better of course because most of the time I hardly noticed it going by”. He speculates about reincarnation and comments on the fact that he never believed in either afterlife nor reincarnation. And what will he be, what atoms will make up his essence when his body is cremated? Or will he just be a free-floating spirit?

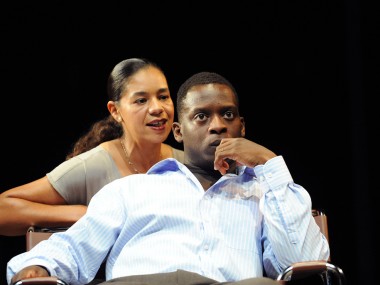

In the third section, an old man (Godfrey again), is being helped out of bed by his carer (Hazel Holder). She helps to dress him, he walks with the help of a Zimmer frame to an armchair, sits down and then, as she helps undress him, gets up and returns to bed. Then they repeat this sequence. Then they repeat it again. Not a word is spoken — after all, what is there to say? But by now the audience is getting restive. At first, in this section, everyone is intensely quiet. I can hear the tick of my companion’s wrist watch. But watching an old man is uncomfortable. There are more and more coughs, people fidget, a few walk out in exasperation. Many just hate the intensity of this 20-minute section. Some switch off and look at their phones. Some are enraged — on the way out they give vent. This, in their minds, is the worst piece of theatre they’ve ever seen. Yes, it’s that good.

In this final scene of a play that can be read either as three unrelated scenes or as the story of one man shown in reverse order, the repetitive actions of the mime of dressing and undressing speak about the basic bodily needs of a life, any life, just as the repeated actions of the black female carer remind us that kindness is part of our mutual survival. The old age that awaits all of us, with luck, has to be endured, but it might also, suggests Churchill, involve situations of inequality. The play’s title implies that the rage against the dying of the light is futile, but also can be read as the lonely care worker’s resigned acceptance of a poorly paid and taxing job. That audience discomfort is not only a protest against being shown a picture of a difficult old age, but it is also a refusal to acknowledge the work needed to look after the gradually dying.

Dominic Cooke directs with meticulous precision on Vicki Mortimer’s grey and austerely neutral set, and 82-year-old Godfrey has an impressive stage presence, both as a vigorous voice asking ultimate questions in the dark and as a frail old man being helped with his daily routine. Holder is beautifully restrained. The rest of an ensemble cast — Madeline Appiah, Susan Engel, Joshua James, Amanda Lawrence, Stuart McQuarrie, Eleanor Matsuura and Alan Williams — animate the opening scene of a play that, however short, stays long in the mind. As does our common mortality.

© Aleks Sierz