Hope Has a Happy Meal, Royal Court

Friday 9th June 2023

This must be leftfield new writing’s sunny summer start. Like Alistair McDowall’s All of It, Tom Fowler’s Hope Has a Happy Meal features striking performances in a story where recognisably painful human emotions — loss of family members — are set in a dystopian vision of the world’s future. In the Upstairs studio space, we arrive in the People’s Republic of Koka Kola, formerly the UK, a hilariously lurid police state where freedoms are acutely curtailed and consumer capitalism is totally dominant. But it’s a dystopia which is drenched with, instead of the usual greyness of Orwellian nightmares, a richly colourful bonanza of bright hues and jolly shopping. Very apt, but what’s the story?

Well, the play is about fortysomething Hope, who returns home after being away for 24 years: she’s trying to reconnect to her half-sister Lor, and after a super opening scene in which she tells a really silly joke, she meets and gets a helping hand from Isla, a trans waitress who is looking after her sister’s baby, while on the run from Wayne, an abusive cop. Soon, the women hit the road. On their way to find the Strawberry Fields commune of Hope’s youth, they are joined by redundant forest ranger Ali, but things soon get very complicated. Fowler’s writing has an instantly appealing brightness and energy, and his renaming of places reveals the ubiquity of big corporations in a nation ruled by a CEO rather than prime minister: Nike International, Samsung Central and Mitsubishi Parkway.

But as well as the joy of this humorously glo-brite vision, and the game show episode in which Hope’s deepest fears are presented in a nightmarish clown-led extravaganza, genuine emotions about the family are powerfully articulated. Lor is angry with Hope because she feels betrayed and abandoned when Hope left — and 24 years is a long time to wait for reconciliation. Her resentment simmers before exploding, and Hope’s own anguish is accurately delineated. At the same time, there is something very touching about the kindness of, yes, strangers. Hope is helped not only by Isla, but also by a random train passenger, a trucker and of course by Ali. Wayne is ghastly enough to be a universal hate figure. Macho men, eh?

Although the quest narrative plotting slackens a bit too much towards the end of this 100 minute show, there are plenty of good passages of dialogue, with some lovely humour. Always tinged with darkness. The lorry driver’s enthusiastic love of country music, which he says has less to do with believing in God, and more about “being in darkness and finding the light”. Having had addiction issues, he knows what he’s talking about. A macabre incident with a noose, a crazy kidnapping and more all contribute to the overall effect. The playtext has subtle references to the long tradition of new writing, by Caryl Churchill, Sarah Kane and Simon Stephens — as well more recent plays by Alistair McDowall and Rory Mullarkey. Great, great, great.

The central image of a quest by assorted misfits who, despite some bouts of bad temper or depression, are shown to be good people (more or less) suggests the play’s politics of small-scale resistance. In this world, the old alternative communes have vanished, forests have been poisoned into sick wilderness, and Ronald McDonald bestrides the globe. Yet despite the infiltration of the market into everything and everywhere, Fowler argues that hope and happiness is still possible (just look at the title, which gets an ironic twist in the play’s ending). And tenderness, and care. If the show wasn’t such fun you could dismiss this as naive wishful thinking, but that would be to underrate the power of being kind in everyday life. It’s a plus that the playwright is unafraid of the strategy of being gentle.

I really like the way that Fowler parodies the banal pronouncements of those in power, and his evident sympathy for the marginalized and the needy. There is also something very allusive in his writing: the mention of Strawberry Fields commune brings to mind the Beatles song “Eleanor Rigby” when, some time later, it becomes evident that we are dealing with a situation that could be described as “all the lonely people, where do they all come from?” I also like the psychological insights, expressed perhaps most directly in the clown game show sequence, and the drunken episode when Hope and Lor get plastered. Yet anger and violence step on the toes of all the humour. Despite all the jokes, notions of loss and death give the piece its much needed shadows.

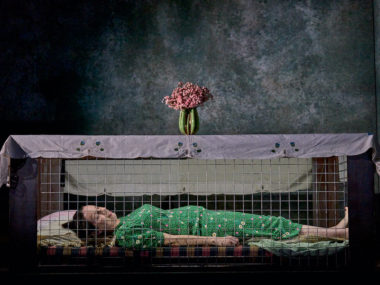

And there is a lot to enjoy in Lucy Morrison’s energetic and often funny production, whose set by Naomi Dawson is versatile enough to host what is in effect a Thelma-and-Louise-style road movie lit up by the neon glare of American culture, with a kinda Big Lebowski vibe. Laura Checkley’s Hope and Mary Malone’s Isla are nicely contrasting characters, and the early comic scenes are the strongest in the play. Amaka Okafor’s Lor is convincingly passionate, and the women are well supported by Nima Taleghani’s Ali and Felix Scott’s Wayne. Most of the cast play several minor roles, which adds to the piece’s epic sweep. So welcome another play that offers a great summer of surreal new writing.

This review first appeared on The Arts Desk