Hysteria, Hampstead Theatre

Thursday 12th September 2013

In playwriting, there’s near-perfection, perfection and oh-my-God-how-I-wish-I’d-written-that. Terry Johnson’s Hysteria, which was first staged at the Royal Court 20 years ago, is definitely in the OMG category. Subtitled “Fragments of an Analysis of an Obsessional Neurosis”, it is now a contemporary classic, and deservedly so. Both a demented farce and a serious study of psychoanalytical theory, both surrealistic and feminist, both arty and troubling, it is also a fantastically brilliant entertainment.

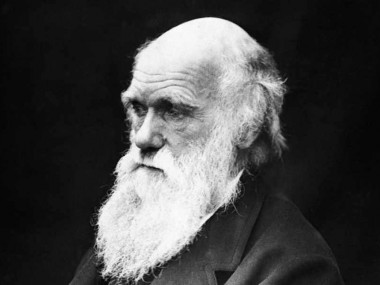

The date is 1938, and we are in the study of Sigmund Freud, who has fled Nazi Vienna and is living at 20 Maresfield Gardens, just off the Finchley Road (in fact, not very far from this venue). He is asleep in a chair; it is five in the morning. Suddenly he becomes aware of a tapping on the French windows — it is Jessica, a young woman looking for the truth about her mother, one of his former patients. For Freud, she was a successful case study, published under the pseudonym Rebecca S; for Jessica, she is someone much more distressed and troubling. As she insists on re-enacting her mother’s psychoanalysis, Freud reluctantly complies. But they are soon interrupted by the arrival of Dali — the surrealist painter with a hyper personality all of his own — and Yahuda, Freud’s personal physician. Because the form of the play is that of a typical English farce, it’s not long before Jessica loses her clothes, Dali drops his trousers, and doors open and close with ever accelerating abandon.

But as well as being a hilarious farce, with bright one-liners dashing around the womb-like comfort of Freud’s study (designed by Lez Brotherston and complete with his couch and archaeological statuettes), this is a serious account of Freudian ideas. So in the second half Johnson stages a thrilling debate between Jessica and the father of psychoanalysis about the so-called Seduction Theory. At first, Freud thought he had discovered that the root of hysteria, and of hysterical symptoms, is repressed memories of real child abuse. But, when the implications of this discovery sank in (surely all of his comfortably bourgeois patients couldn’t have had abusive fathers), he changed his mind. Subsequently, he claimed that his hysterical patients had not been literally abused, but had merely fantasised this abuse. In other words, he came to blame the victims.

So Jessica symbolises the return of the repressed. She offers a believable and heartbreaking feminist critique of the sexist aspects of the great man’s ideas. And since Johnson’s play is a very rich text, this conflict is played out amid a critique, by Yahuda, of Freud’s ideas on the myth of Moses and an analysis of Dali’s art by Freud. Surrealist films are mentioned, there is a joke about Jokes and Their Relationship to the Unconscious, another about Freudian slips, the theory of penis envy is ridiculed, a lobster phone appears and a clock melts off the wall.

Johnson’s compassion and empathy with the victims of child abuse give the play a continuing relevance, and his humour is nimble and surefooted. He directs this revival himself, and the result is a faultless and beautiful piece of theatre. Despite some awkward moments, Antony Sher gives the mortally ill Freud a weary heaviness and a real authority, while Lydia Wilson’s Jessica is gutsy and appealing. Adrian Schiller’s absurdly self-centred Dali contrasts nicely with David Horovitch’s serious Yahuda. Really, this show about a nightmare is a dream.

This review first appeared on The Arts Desk