Imperium, Gielgud Theatre

Wednesday 4th July 2018

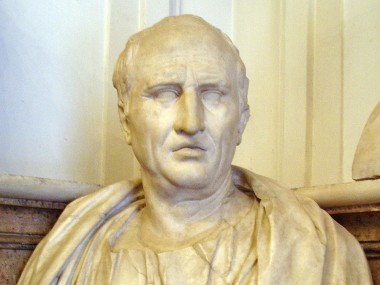

History repeats itself. This much we know. In the 1980s, under a Tory government obsessed with cuts, the big new thing was “event theatre”, huge shows that amazed audiences because of their epic qualities and marathon slog. A good example is David Edgar’s The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby, an eight-and-a-half hour adaptation of the Dickens novel. Today, under a Tory government obsessed with cuts, event theatre has made a comeback: Harry Potter and the Cursed Child (five and a bit hours), The Inheritance (six and a half hours) and now Imperium (almost seven hours). Adapted by Mike Poulton for the RSC from Robert Harris’s trilogy of novels about Cicero, the two-part, six play, drama stamps its mark on the West End after opening in Stratford last year.

The two parts, called Conspirator and Dictator, tell the 30-year story of the last days of the Roman republic as it first resists the conspiracies of Catiline and then Clodius, before succumbing to the power grabs of Julius Caesar and then Octavian. The first evening shows how Cicero, a lawyer and orator from a humble background, manages to succeed, despite the sneers of the aristocrats in the senate, and get elected by the people as a consul. As he fights off the conspirators, who aim to turn the Republic into a dictatorship, he becomes “the Father of the Nation”. The second evening shows how, hubristically, Cicero’s vanity ultimately leads to failure.

As with Harris’s novels, which are a gripping read and full of detail about power, politics and public speaking, Cicero’s story is told mainly by Tiro, his well-educated slave and scribe. The rapport between the two men, both scholars who have been caught up in violent times, is sometimes funny, sometimes touching and often a bit fraught. There are lots of wry jokes in their interplay. When Tiro confides in the audience that he is writing his master’s biography, Cicero interrupts him by saying, “This is getting very expositional.” At another point, Tiro asks the audience to “try to keep up” because, he admits, “a lot of the characters are called Gaius”. Yes, you really need to know an outline of ancient history to understand what’s going on.

The plays are all about power (what else?), with issues of justice, democracy and corruption thrown in for good measure. There’s a lot about social snobbery, and about military might. And although at first Cicero appears to be a hero — protecting the democratic values of the Republic against the self-interest of titans such as Julius Caesar, Pompey and Crassus (the programme has some explanation about who is who) — he is also mired in falsehoods and manipulations. As he admits, “Politics is a dirty business.” But, then, so is saving the ideals of the Republic. And, the story seems to ask, what is best: manipulation for the sake of a public ideal, or manipulation for personal greed?

I have to say that although I find the story engrossing, Poulton’s adaptation is quite pedestrian. It has the virtues of clarity and simplicity, but his language is rather thin, even when spoken by the oratorical Cicero. (Some of the best bits are the set speeches.) The two long plays also offer easy, perhaps too easy, parallels to our own times. The great Pompey, a military chief, has a Trump-like hairdo and his self-regard is modelled on the president’s. All of the politicians invoke the will of the people, and use the bombastic rhetoric that sounds so familiar to us today. And, at the risk of sounding like a metropolitan elitist, it’s hard to disagree with Cicero’s verdict that “Stupid people tend to vote for stupid people”, or, more controversially, Cato’s remark: “What business do we have in Syria?”

In the second part, the pace and intensity of the story seems to slacken and the eventful messiness of history clearly defies all attempts to tame it. Even so, Julius Caesar gets dispatched with shocking speed, and Mark Antony’s bid for supremacy is countered by the youthful Octavian. With Cicero visibly aging, and his family life falling apart, there is more pressure on his relationship with Tiro, which remains the centrepiece of the adaptation. Still, there such a lot of detail about Roman politics, and so many characters, that a certain tiredness sets in. However, the laughs keep coming: at one point, there’s a good joke about Caesar and Britain, “a poky little hole somewhere just beyond Europe”.

This Roman tale is magnificently epic, with RSC top man Greg Doran directing and designer Anthony Ward creating a flight of senate steps, which doubles for a dozen other locations, above which a massive sphere suggests the global reach of Empire. At different times, this reflects snakeskin or fire or starlings to comment on the action below. In the background two large watchful eyes picked out in cobblestone mosaic survey the tragic events. Under their scrutiny, Richard McCabe (Cicero) and Joseph Kloska (Tiro) take us by the hand through the complications of the plots and plotting. I have to admit to having doubts about McCabe, who although totally committed to the role is here too light-hearted an actor for my taste, often prancing about, and less intellectual than Cicero should be, but they do make a good double act. In the second part, McCabe’s mannerisms continue, but by visibly aging he acquires more gravitas.

The rest of the huge, mainly male, cast — most of whom play two parts — includes a powerfully energetic Joe Dixon as both Catiline and Mark Antony, David Nicolle as a rather campy Crassus, Peter de Jersey as the sinister Caesar, Nicholas Armfield as Clodius and Michael Grady-Hall as Cato. The women, who have a much smaller presence, are played by Siobhán Redmond as Terentia (Cicero’s hard-headed wife), Jade Croot (Tullia their daughter) and Eloise Secker (incestuous Clodia and then screechy Fulvia). With stirring music from Paul Englishby, this is certainly a major theatrical event — Cicero’s speeches, with their mixture of sarcasm and idealism, are great, but not everyone will enjoy the comic interpretation of some of these characters, and the storytelling does get a bit bogged down in the second part.

This review first appeared on The Arts Desk