Inadmissible Evidence, Donmar Warehouse

Tuesday 18th October 2011

John Osborne was the great founding father of contemporary new writing for the theatre. In 1956, his Look Back in Anger at the Royal Court changed British drama for ever, and his subsequent work explored the subjects of failure and national identity in language that is both highly rhetorical and at the same time frequently feels as if it is torn from the gut. His 1964 play about the washed-up London solicitor Bill Maitland, which opened tonight in Jamie Lloyd’s revival, is one of his masterpieces.

The story shows the mental disintegration of the middle-aged Maitland during two days of personal and professional hell. It starts with a nightmare as he dreams that he has been arraigned for “having unlawfully and wickedly published a wicked, bawdy and scandalous object intending to vitiate and corrupt the morals of the liege subjects of our Lady the Queen”. This object turns out to be himself. And the play then shows how he becomes increasingly isolated from Hudson and Jones, his work colleagues, from Joy his secretary, from his clients, from his wife, from his lover and, so painfully, from his daughter.

As the structure of the play mirrors its protagonist’s crack-up, Maitland’s breakdown is illuminated not only by his awareness of his own mediocrity but also by his antagonism to modern life. Fired up by alcohol, he radiates both personal anguish (especially the fear of being found out) and a thoroughly subversive attitude to youth, young couples, family life and every institution of the state. In the face of modern science, technology and social reform, Maitland lets out an almighty fart of boozy defiance.

As fresh as when it was first written, the playtext is clearly Osborne’s fantasy of how a man should behave if he wants to live truthfully and passionately. There’s a lot about self-knowledge and courage here. And the brittle nature of the fantasy, its detachment from reality, only adds to its conviction. Like many of Osborne’s characters, Maitland loves women, but treats them very badly. The play is both a cry from the heart and a report on the crisis of middle-aged masculinity.

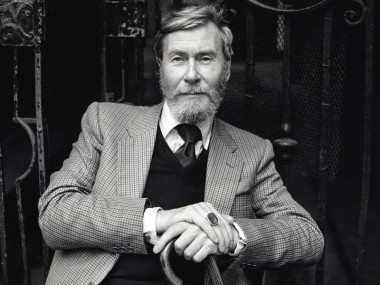

In the central role, Douglas Hodge is extraordinary. The part is more or less one long monologue and he plays it as if it was some kind of insane musical instrument, his voice rising to shrill notes or tumbling into bass growls, at once seductive and off-putting. With his amusing mimicry, his vocal flourishes, his funny voices and funnier walks, he dominates the stage, whether striding across it or collapsing into a chair at his desk. In this bravura display, Hodge engages the audience, eyeing up the women, taking the hand of someone in the front row, and literally playing to the gallery. It’s extravagant, amazing and — up to the interval — very entertaining. In the second half, as Maitland becomes increasingly solipsistic, the going gets tougher.

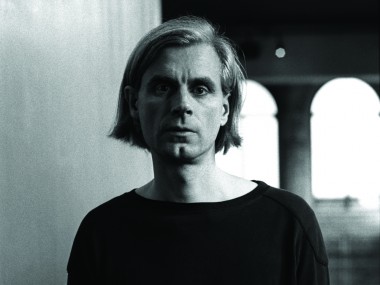

Lloyd’s spirited revival is set in an untidy office, designed by Soutra Gilmour, and has a solid supporting cast led by Daniel Ryan as Hudson, Al Weaver as Jones and Amy Morgan as Joy. Serena Evans plays a succession of female clients. But the plaudits belong to Hodge’s astonishing performance. Watching Maitland’s decline is never easy, and it’s not meant to be, but Hodge rewards you whenever he dares to tear out his soul — which is more often than in any other version I’ve seen of this play. After some 140 minutes of agonised declamation and rasping rants, you leave the theatre thinking how few contemporary plays have a fraction of Osborne’s energy, or daring, or feeling.

This review first appeared on The Arts Desk