Lemons Lemons Lemons Lemons Lemons, Harold Pinter Theatre

Tuesday 31st January 2023

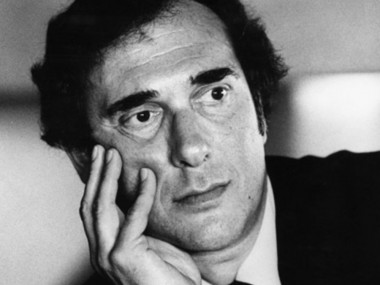

Culture which arrives from the margins to the mainstream is a classic phenomenon. In the case of Sam Steiner’s Lemons Lemons Lemons Lemons Lemons it has taken almost a decade for this two-hander to make the journey from a student production at Warwick University, via the Warwick Arts Centre in 2015 — plus outings to the National Student Drama Festival and Edinburgh Festival — before finally arriving in the West End. Since he first wrote it, the play has been a fringe favourite with several revivals, but this time the two-hander boasts a star cast familiar from TV: Aidan Turner (Poldark) and Jenna Coleman (Victoria). But can a small experimental play flourish in a glitzy mainstream production?

Written as a fractured narrative that keeps jumping back in time, and then forward again, Lemons is a blend of rom-com and dystopian fantasy. An odd couple, Bernadette, a rather conservative but ambitious lawyer, and Oliver, a laidback but rebellious musician, meet at a pet cemetery. Cute. As they deepen their relationship, with some neatly awkward moments, they discuss how the language of love from former liaisons can sometimes carry over into new ones, and how old endearments (Babycakes?) might be out of place with another lover. They are attentive to language: at one point, Oliver makes a fuss about how Bernadette uses the word “really”, only to be exposed as a hypocrite a few moments later.

But the issue of language becomes a dystopian nightmare when a populist party wins the general election and passes a Quietude Bill which radically restricts the amount of words a citizen can speak to 140 a day. There are legal protests and demonstrations, but the law remains in force. As the government hushes all protest, Bernadette and Oliver have to find other ways of communicating, from Morse Code to clumsy mime. It has to be said that the dystopian element of the play requires quite a big dose of willing suspension of disbelief. Given that Oliver is a radical who leads protest marches, it strains credibility to imagine that he would accept this word limit — especially as his relationship with Bernadette suffers when they can’t communicate.

Even if you do accept, as you have to, the play’s central conceit, it’s hard to believe that Oliver and Bernadette are, in this new situation, so clumsy and wasteful with their words. In stories such as these the gesture of the fiction is to challenge the audience to think how they would behave if they were in a similarly Orwellian nightmare — but this time, all I could think about is how slackly written the dialogues are. I kept wanting to shout: “Use your words more carefully.” But I didn’t and they don’t. Nevertheless, as a fable for our time, Lemons does remain relevant: the current government would love to radically censor speech and protest — and the referendum in the play is an uncanny prediction of the Brexit vote. Then when news emerges of politicians ignoring the new laws, a distinct whiff of Partygate is clearly detectable.

As a piece of writing, some of Steiner’s play has a strong metaphorical force, and he is good at both random facts — the average person speaks some 123 million words in a lifetime — and at showing how words can conceal as much as reveal a person’s feelings. The way that Oliver and Bernadette respond to the restrictions that are imposed on their lives reflects the more usual strains of poor work-life balance, and there is a good sense that saving up most of your 140 words to use with your lover is an act of affection — when either of them uses most of their words outside the home it feels like a betrayal. That said, the emotional problems — boredom with sex, cheating with another — are sketched in with a rather frustrating brevity.

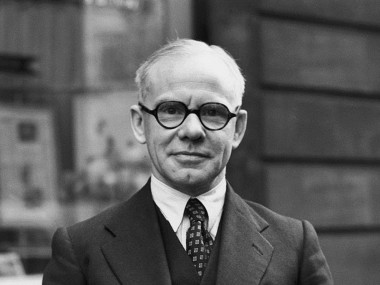

If most of the energy of the writing is used up by keeping the fractured form of the plot intact, the cost — which is more obvious on a large stage than in a small studio space — is that the emotional life of the characters is less well apparent. It has to be said that, as in many plays by Martin Crimp, both halves of the couple are not very attractive. She is a bit too self-controlled, he is a bit too ragged. Also, the shadow of Caryl Churchill looms over the play’s experimental form. Finally, in comparison to other two-handers that have made the trek from margins to mainstream, such as Nick Payne’s Constellations or Duncan Macmillan’s Lungs, Lemons feels as if it is not quite big enough to fill a large stage. This might not be completely true, but certainly there is a chilly atmosphere to this show.

While both Coleman and Turner, in Josie Rourke’s hi-definition 90-minute production, deliver detailed performances, the relationship feels very cool, even when Turner gets a bit insecure and Coleman a bit angry. Some moments, as when he has to sit down after losing the vote, have a strong impact, and her face occasionally shows her pain and disappointment, but the awkwardness of their initial meeting works better than their developing relationship. The set, designed by Robert Jones, is distractingly beautiful, with its shooting lights, and changing series of compartments, full of the objects of daily life. In the end, the rather cool perfection of the production works less well than fringe versions of the play, whose intimacy gives it a more powerful sense of life.

This review first appeared on The Arts Desk