Living with the Lights On, Young Vic

Thursday 17th March 2016

Recently, I’ve been meeting some very agonised people in the theatre. Fictional people. On stage. Lots of agonised women; lots of agonised men. Agonised kids; agonised teens; agonised adults. A lot of these encounters have been monologues; a few have been two-handers. Several have had a public health agenda. And the latest is Mark Lockyer’s Living with the Lights On, an 80-minute monologue about bipolar disorder, and it’s just as frayed and fraught as all the others.

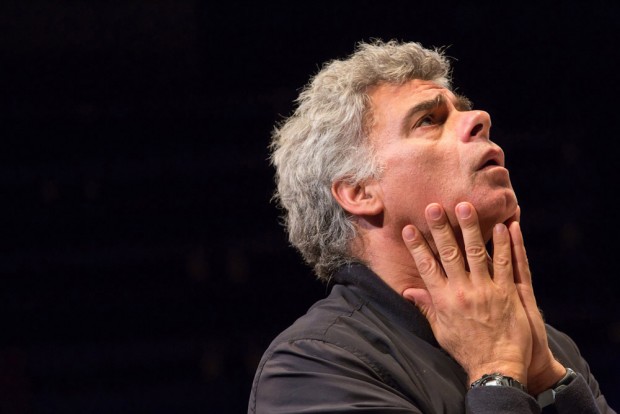

It starts with Lockyer, who is a Shakespearean actor with an impressively long and varied CV, welcoming us into the studio theatre at the Young Vic. We are offered tea; we are offered biscuits. Lockyer asks us for our names. The atmosphere of studied informality is confirmed by the staging, a space which has no props apart from a ladder, some lights on the floor, a table with plastic glasses filled with water, a cloth, and the tea and biscuits table. Oh, and a picture of the Devil. We’re in a rehearsal room and no one is pretending otherwise. It’s a blank place and so our attention focuses on Lockyer.

After offering thanks to David Lan, the venue’s artistic director, and making a joke about the “fourth wall”, Lockyer gets down to business. He has a story to tell, and he starts to tell it. It begins extremely casually, one warm Friday afternoon in Putney, with the actor lying on a sofa in his briefs. He’s listening to Robbie Williams’s “Karma Killer”, which begins with the admonition: “You’ve been naughty, very, very naughty.” Then the phone rings. It’s Adrian Noble of the RSC and he offers the actor the part of Mercutio in his upcoming production of Romeo and Juliet. Great! So far so good.

But when Lockyer gets to Stratford-upon-Avon, his troubles begin. On the banks of the idyllic river he meets the Devil, or Beelzebub to be exact. Or Bee for short. This Mephistophelean figure, a delusion in the actor’s manic mind, prompts him to do some very weird shit. Which at first seems perfectly reasonable. Bee tempts him to get off with Poppy, even though he already has a girlfriend in London. Then he tempts him to break with his girlfriend; then he tempts him to do other much worse stuff.

Lockyer’s monologue has the quality of a teach-in. With great intelligence, a fair deal of subtlety and lots of humour, he outlines what it feels like to experience an acute manic-depressive episode. Starting with the emotional confusion of sexual infidelity, and its rich mix of desire and guilt, the monologue spirals into ever more extreme incidents that become increasingly toe-curling to listen to. Lockyer’s account of going on stage as Mercutio — and promptly dropping dozens of lines from his Queen Mab speech — is bad enough, but even worse are his suicide attempts and arson attacks.

Seen from his subjective point of view, you can understand the reasoning behind these outrageous acts, while at the very same time appreciating the appalled reactions of his lovers, his friends and his colleagues. And this intellectual understanding goes hand-in-hand with emotional sympathy. You feel his distress. Because bipolar is sad. Despite all the fizz in its most manic phases. Ultimately, the manic-depressive is utterly alone.

At first, Lockyer comes across as frighteningly volatile. He is loud; he is aggressive; he is unpredictable. When he shouts at another member of the audience, you’re just glad it’s not you. Gradually, as the evening progresses his mimicry of the other characters of the story — directors, actors, stage managers, therapists, medics, family members, police officers and judges — becomes acuter and his own onstage character goes into one of those convincing free-flows that make you doubt the gap between fiction and fact. Suddenly, all of the show’s gimmicks — the tea, the biscuits, the bonhomie — fall away and all that’s left is Shakespeare’s “poor, bare, forked animal”, “unaccommodated man”. It feels like a triumph.

Finely directed by Ramin Gray for the Actors Touring Company, Lockyer’s story is darkly humorous as well as starkly frightening. You have to admire the courage and skill with which he walks the border between a terrible real-life experience and its theatrical representation, and they way he slowly sheds the more actorly aspects of performance to find the raw emotional truth underneath. Living with the Lights On is both a vividly experiential play, and an unforgettable account of mental collapse.

© Aleks Sierz