Luna Gale, Hampstead Theatre

Monday 22nd June 2015

American playwrights are often rightly praised for their plotting. But sometimes a good plot can get in the way of other aspects of play-making, such as characterisation and credibility. A case in point is veteran US playwright Rebecca Gilman, whose Luna Gale was first seen at the Goodman Theatre in Chicago in 2014, and then received the American Theater Critics Association New Play Award. In his programme note to this production, Edward Hall, the artistic director of the Hampstead Theatre, puts Gilman’s play in the context of his programming of a “string of wonderful American plays” and praises her “confidence with the craft of writing for big proscenium theatres”. But does her play live up to the hype?

Set in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, the story centres on Caroline, a social worker with 25 years experience who has to sort out the case of Luna Gale, a baby born to Karlie and Peter. After baby Luna is admitted to hospital suffering from diarrhoea and dehydration, her parents are accused of child neglect. Because both of these teenagers have drug issues, temporary custody of the child is given to Karlie’s mum Cindy. The problem with Cindy is that she is a fundamentalist Christian who believes that the Last Days are imminent — and she wants to save Luna’s soul.

Religious belief does not make Cindy a bad mother, but it does give her the motivation to make a court application to adopt the child on a permanent basis, despite the objections of her own daughter. So Caroline comes under a variety of pressures not only from Cindy, but also from Cindy’s Pastor Jay. Likewise, her new boss Cliff clashes with her over the correct way of settling the case. Without giving too much away, some of the credibility of this situation is undermined when we see Caroline acting insensitively — using the phrase “crazy Christian” is not a good idea in Iowa. Surely, as an experienced social worker she should know better.

Anyway, Gilman’s play has barely started, and there are several plot twists to come: a variety of issues — drugs, abuse and belief — are introduced, and the theme of bureaucracy versus good sense results in some comedy. For example, Caroline suggests that Karlie should join a support group called Mothers Off Meth, or MOM for short! But despite its good sense and insights, the play is overloaded with plot and Gilman’s characterisation is a bit superficial. Oddly enough for such an experienced writer, there is a wholly unnecessary subplot involving another teen, Lourdes.

At its best, the play examines the way that abuse is handed down through families, and shows the distressing effects of government cuts to welfare provision. Gilman’s insights into religion — as a drug, or a cult — are deftly delivered, and there is a good joke about Jesus as a personal trainer. But speed of storytelling is achieved at the expense of depth, and — as always — Gilman’s writing is just a bit too polite for its own good. You never feel that she really connects emotionally with the feelings she describes. Except for a horrific account of child abuse, which silences the audience, most of the play is curiously lacking in impact.

One problem with the production is religion. While in the United States the scene when the pastor prays for Caroline’s redemption might have been a serious moment on stage, here on press night it was greeted with derisive laughter. British audiences, it seems, just can’t take belief seriously. Another problem is that, just before the interval, Gilman introduces the idea that Caroline is a good person who has decided to do the wrong thing for (maybe) the right reasons. This creates a watchable thriller, but at the expense of our sympathy with the lead character.

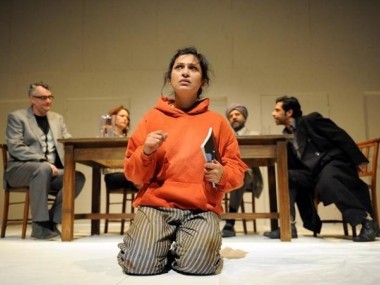

Director Michael Attenborough returns to the main stage of this venue for the first time since he was artistic director here in the early 1980s and directs with his customary clarity. And his cast is good. Sharon Small plays Caroline with an excellent mixture of earnestness and a crippling sense of her own pain, while Rachel Redford and Alexander Arnold are the contrasting, and troubled, teen parents. Caroline Fraser (Cindy), Corey Johnson (Jay), Ed Hughes (Ed) and Abigail Rose (Lourdes) provide solid support. Although this piece is perfectly topical in its account of how shrinking welfare budgets hamper the recovery of addicts and how huge caseloads turn conscientious social workers into cheats, burning them out in the process, the play is neither nuanced enough nor gut-wrenching enough to be more than an evening of light entertainment. In this case, the craft of the writing gets in the way of creating a really good play.

© Aleks Sierz