Misty, Bush Theatre

Wednesday 21st March 2018

In the past quarter of a century, black British theatre has boomed. Playwrights such as Roy Williams, debbie tucker green, Kwame Kwei-Armah, Bola Agbaje, Oladipo Agboluaje, Michael Bhim, and more recently Inua Ellams, Nathaniel Martello-White and Charlene James have reinvigorated the language and exploded the preconceptions of contemporary theatre — they have introduced audiences to new worlds as well as new words. If you take a look at the National Theatre’s Black Plays Archive, there are just three plays in the 1950s; for the 2000s there are at least 100. But, given this variety of talent, why do theatres push black writers into writing a limited amount of plays?

You know the kind of thing I mean. Plays about black youth that are full of street slang, criminal acts and violent conclusions. Stories about gun crime, knife crime and domestic abuse. If it is these clichés of black British experience that dominate contemporary drama then is this because the mainstream audience is more comfortable with this than with more complex representations of people from different ethnicities? In Arinzé Kene’s Misty, this issue is highlighted and the clichéd view of any so-called “black play” is comprehensively criticized. In his Preface to the play text, Kene tells the story of how Misty came about: he was talking to an usher at the Young Vic and found himself provoked by the young man’s use of the expression “black play”. You can see his point: after all, we don’t talk about “white plays” do we?

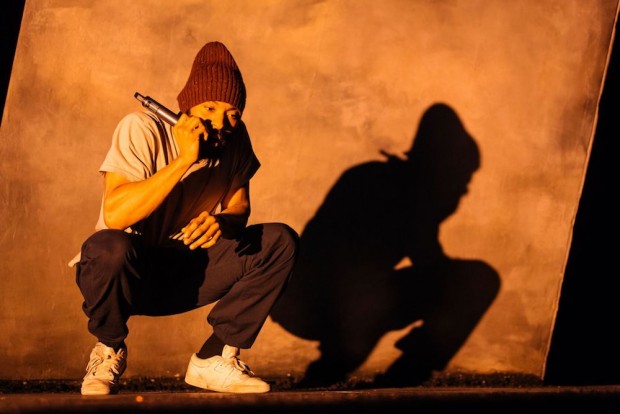

Misty is an exciting hybrid: it’s a gig, it’s a performance poem, it’s a one-man show, it’s theatre about theatre. Starting off with a typical urban story of a fight on a night bus, Kene talks about the events that have befallen Lucas, a young black man, his daughter Tracy and his fuck buddy Jade. But the slender story is less important then the metaphor. At the beginning of the piece, the protagonist sees himself as a virus, an infection of the body of the city, an outsider changing the environment, maybe a disease of normality. The rest of humanity is the blood cells; he is the virus. By the end of this two-hour show, Kene changes his mind: he was wrong, his character is not a virus but a blood cell. The real bad viruses are the hipsters and the gentrifiers.

But the politics of Misty are even more evident in the interruptions to Kene’s monologue. His friends, Raymond and Donna, break in. They criticize him for writing stories that are full of harmful clichés about “generic angry young black men”. They accuse him of selling out, of creating images of black youth that pander to the prejudices of white audiences. He’s just written another “urban play”, another “black trauma” play, another “nigga play” — “urban safari jungle shit”. And they are not the only ones to pressurize him. His producer, his agent and even his older sister add their criticisms. His lover Dimples walks out on him. No one can leave him alone; everyone wants him to write something different.

Using a mixture of rhythmic poems and spoken narratives, all to the melody and the beat of Shiloh Coke and Adrian McLeod’s drum-and-synth score (they also double as the voices of his friends and the other characters), Kene discuses the issues of authenticity in representation (do white people dominate our view of what a black play is?), urban gentrification (do white people move into a poor area and expel its black residents by pushing up house prices?) and poverty (do white people support police prejudice and brutality against black youth?). Through repeats and yet more repeats, beats and yet more beats, a vivid picture of an artist struggling to make sense of his writing comes through.

As theatre there are several memorable moments: director Omar Elerian uses a rich palette and a visual metaphor — orange balloons — whose rubbery bright texture at first defies Kene’s ability to burst the bubble he’s in, and then engulf him completely, before spilling all over the stage. As he fights back, bursting these bubbles of restraint, he gets covered in paint powder. Rajha Shakiry’s design and Daniel Denton’s projections add to the changes of atmosphere and focus. The sounds are satisfyingly loud. At one point, his older sister is played by a young girl in school uniform (suggesting that we never quite lose our earliest experience of our family members).

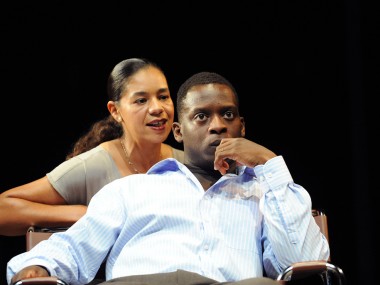

At the centre of the show is Kene himself. Having just finished his part in Conor McPherson’s Girl from the North Country in the West End, he devotes all of his considerable charisma to this meditation on the race politics of storytelling. He moves, he grooves, he sweats, he falls, he admonishes us, he appeals to us. He is us. Although the narrative he has invented about Lucas is, he argues, based on truth (he flashes a dictaphone) it can’t be simply told because it keeps slipping into racial stereotyping. Worse than that, it is a very thin story anyway. But the postmodern self-reflexivity of Misty throws up enough material for the audience, of whatever ethnicity, to get its teeth into. If, not for the first time, the voices that are loudest in condemnation of black playwrights come from others in their own community, this show’s finale is a foot-stamping gesture of thrilling defiance.

© Aleks Sierz