Moon on a Rainbow Shawl, National Theatre

Wednesday 14th March 2012

Like many a regular theatregoer, I have a little list of classic plays that I’ve never seen, or even read. One of these is, or rather was, Errol John’s evocatively titled Moon on a Rainbow Shawl. Written in 1953, this definitive “yard play” was a historic breakthrough for Caribbean playwrights in Britain. So it was with considerable anticipation that I went to this revival, which opened tonight at Britain’s national flagship venue. But can this classic stand up to scrutiny?

Originally, the 33-year-old Trinidadian-born John, who was working as an actor, won the Tynan-inspired Observer new play competition in 1957, and his drama was put on at the Royal Court the following year, although such was the racism of the West End at the time that a promise to put it on at a Shaftesbury Avenue venue was soon broken. John was so offended by this vile treatment that he later insisted that there could be no revival unless he directed it. This finally came to pass at the Theatre Royal Stratford East a couple of years before his death in 1988.

Set in a sweltering Trinidadian yard in a poor part of Port of Spain, the play examines the lives of a group of neighbours. On one side live Charlie and Sophia Adams, who have a newborn baby and a young daughter, Esther, who is about to go to secondary school. Across the yard lives Ephriam, a trolleybus driver about to be promoted, and close by is Rosa, his lover. Above him lives Mavis, who picks up American servicemen by night and goes out with the charmer Prince by day.

Two storylines intertwine like tropical vegetation: the main growth concerns Ephriam, who plans to migrate to England, while his lover Rosa hopes to detain him. Across the dusty yard, Sophia despairs of the fecklessness of her husband, Charlie, who likes a night with a bottle of rum and his mates. Although their daughter Esther is bright enough to go to secondary school, can the family afford to buy her uniform? And if not, what will happen?

This is a traditional well-made play that slowly winds and weaves like a river, occasionally becoming muddy and sometimes slowing down in the backwaters. Unlike most plays of the 1950s, it shows an enormous range of characters and social types: there’s a calypso player, a policeman, a cricketer, a cab driver, a drunk loafer and a landlord. We hear of passing fish vendors and ice sellers. Local kids play nearby. There is a vibrant sense of life being lived in the close company of other people.

John’s writing has fluidity and clarity, with spicy moments and some wicked jokes. At some instances, it throbs with Caribbean vernacular; in some passages, it embraces poetry. There’s heat, sex and good humour. John has listened well to the mocking tongues of women and respects the authority of parents. He also understands sadness and despair. Although much of the language is unnaturally clean, perhaps this is due to the theatre censorship of the 1950s.

In the background lie the thematic mountains that surround the smaller stories of the yard: long after the end of the Second World War, West Indian soldiers are finally coming home, a reminder of their contribution to the struggle. Cricket is important to the island’s culture and identity. Equally important are the dream of migration to a better life, the exploitation of the poor by the well-off, female suffering and the influence of the “Yankee dollar”. There is sex, crime, shame and food.

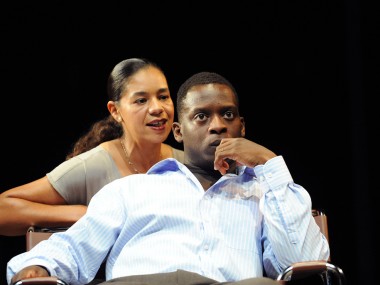

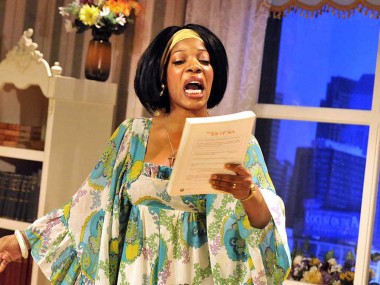

Michael Buffong’s good-humoured production is charming enough, but Soutra Gilmour’s set never quite captures the squalour that underlines the story’s desperation. On a traverse staging, which has some poor sightlines, Buffong stresses the generosity of the writing and is greatly helped by good performances all round. Danny Sapani’s towering Ephriam conveys a real desire for justice as well as a stubborn desperation to escape. Martina Laird’s wise-talking, resigned and finally ravaged Sophie contrasts nicely with Jude Akuwudike’s backward-looking and broken Charlie. Tahirah Sharif’s Esther has youthful vigour while Jenny Jules’s Mavis is spirited and mouthy. But although the cast can be proud of their performances, a feeling remains that this play will be more honoured than enjoyed.

This review first appeared on The Arts Desk