More Life, Royal Court

Wednesday 12th February 2025

I always advocate in favour of more sci-fi plays, and over the past decade there have been a gratifying number of them. But one essential element of any futuristic fantasy must be its power to convince. And it is precisely this that is missing from Lauren Mooney and James Yeatman’s More Life, currently in the studio space of the Royal Court. These two theatre-makers, who run the Kandinsky theatre company, have had a good light-bulb moment: how would you, and your nearest and dearest, cope with the reality of eternal life? Set in 2075, the play shows how Bridget — who was killed 50 years ago in a car accident — is brought back to life. How will her husband Harry, now in his eighties, and his second wife, Davina, react to her return from the dead?

More Life begins with a story, set in 1803, about a hanged man whose body is galvanized by electricity — thereby suggesting the possibility of resuscitation. Back to the future, a scientist called Victor (one of several nods to Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein) keeps trying to bring the long-dead back to life, as a way of selling the new immortality. However, although he finally succeeds in reanimating Bridget’s consciousness, he has to swap her long-gone body with a synthetic creation of metal, plastic and wire. The android doesn’t look like the real Bridget, but it does have her thoughts and memories. And it cannot die.

When Harry and Davina meet this new Bridget the psychological tensions inherent in the project come into focus. Due to advances in medical science the old couple look youthful, with 80 clearly being the new 50, but their memories of their youth are distinctly hazy. So Harry wants Bridget to remind him of his younger self, while Bridget finds this older Harry very different to the young husband she remembers. Added to this are the reactions of Davina to her husband’s first wife, who as an android looks completely different from any photo of the real Bridget, and who knows nothing about what has happened in the past 50 years. This is all quite intriguing, and would have made for a neat 90-minute play.

Instead, Kandinsky have put together a rather ungainly creation, almost a kind of Frankenstein’s monster, which has a noisy narrative chorus, conflicts between Victor and his assistant Mike, some satire on carbs in cooking, attempts at dystopic commentary, a bit of song and dance, and some frustratingly inconsequential storytelling. Oddly enough, whenever the material starts to become interesting, or the characters acquire some fleshy humanity, Mooney and Yeatman change tack, throwing in some comedy, or veering into a new groove. Most of the human themes, about class and race for example, seem to have thrown a sickie — and we miss them, we miss them.

More Life is a bumpy ride, and not in a particularly good way, lacking any authentic writerly voice and instead making references not only to Shelley, but also to the open texts of Martin Crimp, the horrors of in-yer-face violence and the much more fertile imagination of Caryl Churchill. While the play will certainly appeal to anyone who loves a dystopic comedy of manners, with frankly silly situations, I’m irritated by the way it avoids exploring its own central ideas. Since Bridget is alive as a hard drive rather than flesh and blood, can she feel as well as think? What would AI-powered feeling be like? Can the new Bridget learn new ideas and have fresh experiences?

Sadly, none of these intriguing questions get more than a glancing mention, and — unlike streamed shows such as Upload or Cassandra — there is no sense of a deeper human connection with the themes of death, returning to life and living for ever. Having created the new Bridget, Mooney and Yeatman seem content to clown around and let her drift out of their control. Much of the dialogue is unconvincing and goes nowhere, even though some of the piece’s best ideas beckon from a distance. There’s a lamentable lack of emotional depth, with a much more superficial vibe zinging around the stage. Whenever the ghost of the younger Bridget appears, my spirits rise, only to be dashed again.

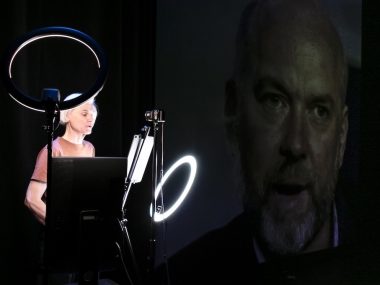

Directed by Yeatman from Mooney’s text and dramaturgy, on Shankho Chaudhuri’s strikingly orange set, the cast playfully engage with the story’s comedy as well as its portentous moments. Alison Halstead plays Bridget with enormous restraint, and more than a suggestion that living in a plastic body is no fun, a great contrast to her lively former self as performed by Danusia Samal. Marc Elliott’s wildly passionate Victor clashes with Lewis Mackinnon’s mildly good-natured Mike, while Tim McMullan’s Harry and Helen Schlesinger’s Davina embody the privileged rich couple. But there is not enough humanity in the characters to appeal, and not enough room for the ideas to fully develop. Help! Do not resusitate.

This review first appeared on The Arts Desk