The Nether, Royal Court

Thursday 24th July 2014

There is so much public anxiety about paedophiles on the internet that it’s surprising that so few plays tackle the issue. Now Los Angeles playwright Jennifer Haley brings her new play on the subject, which won the 2012 Susan Smith Blackburn Prize, to London after winning awards in the States. She takes a sci-fi approach: in the near future the internet has evolved into the Nether, a virtual zone in which all the senses can be stimulated — and this is a potential paradise for paedophiles.

Here is the set up: Sims is a successful businessman who has developed the Hideaway (a future version of our darknet) in an obscure corner of the Nether. Here he is able to entertain clients who arrive in the form of avatars and can have sex with the avatar of a little girl called Iris. But who is Iris in the real world? A grown-up woman? A grown-up man? And does it matter? After all, surely this is just harmless fun — a mere fantasy with no repercussions in the real world.

Asking these questions is Morris, a young female detective whose mission is to hunt down online paedophiles — even if they deal only in digitally created images (as opposed to pictures of real-life kids). She interrogates Sims, and has also arrested Doyle, a prize-winning science teacher who is one year away from retirement. His interest in the Hideaway is clearly suspect. But will he talk?

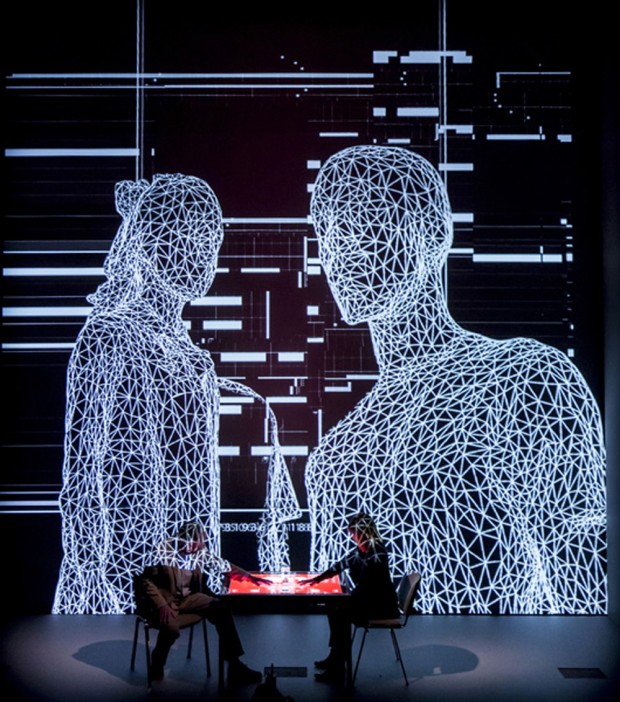

In between scenes set inside the grey interrogation room, Haley and her team create scenes that take place online in the digital universe. Here the colours are deliberately heightened, although some of the furniture is just sketched out. It looks like a very good video game, with avatars moving just like human beings. We watch Sims, whose avatar is called Papa in this world, talk with Iris, a lovely pre-pubescent girl. Then he is visited by a new client, named Woodnut. What does he want?

Haley writes with great clarity and economy, telling this tale of perversion and detection in barely 80 minutes. But the texture of her language is thin and although she outlines the issues with sympathetic understanding and remarkable simplicity, there is precious little trace of the real stink of desire in her dialogues. There is nothing to make your toes curl in anguish. Most disappointingly, all her characters turn out to be nice people — despite the dodgy urges some of them seem to have.

I enjoyed the discussion of the questions already spawned by the internet: if the virtual world is unreal, a fantasy, how can it be either good or bad? How do we judge the ethical content of made-up images and the actions of avatars? Is it true that what we do in the virtual world has no consequences in the real world? The Nether, rather predictably, ends up by preferring the real world to the virtual one, and traditional morality to the excuses cooked up by perverts.

What makes this finger-wagging approach bearable is the sheer brilliance of the visual side of the production. The scenes inside the Hideaway have been created with enormous flair and have a vivid stickiness that etches itself on the imagination. The lights and sounds of digital life combine to pull you into a delightful netherworld, designed with memorably loving care by Es Devlin, Luke Halls and Ian Dickinson. Thanks guys — you really rock!

Directed with empathy and intelligence by Jeremy Herrin, in a co-production with Headlong theatre company, the play features solid performance from Stanley Townsend (Sims), Amanda Hale (Morris), David Beames (Doyle) and Ivanno Jeremiah (Woodnut). The part of Iris is shared between Zoe Brough and Isabella Pappas. But however beguiling the production, I missed the sense of real danger that a better text might have explored. Never mind, I’m sure this will make a good film.

This review first appeared on The Arts Desk