Next Time I’ll Sing to You, Orange Tree Theatre

Friday 11th November 2011

Some plays are so weird they defy description. Well, almost. One of these must surely be the late James Saunders’s deeply absurdist play, whose first outing in 1963 launched the career of the young Michael Caine. Soon after, its author won a promising playwright award. The current revival, part of the Orange Tree’s 40th-birthday season, gives us a chance to look again at a writer whose innovative work has been consistently promoted by Sam Walters, artistic director at this address.

Darkness. A man lies under a starry night. Actors, and other creatives, arrive on stage. Who are they and what are they doing here? Meff, a joker who likes a quiet smoke, tries to get things going, but needs the help of Dust, a silver-tongued philosopher. Maybe Lizzie, the identical twin of another woman called Lizzie, can help them? Maybe not. Until the show begins, all three are trapped on stage, just as they are every night, waiting, if not for Godot, then for the story to start.

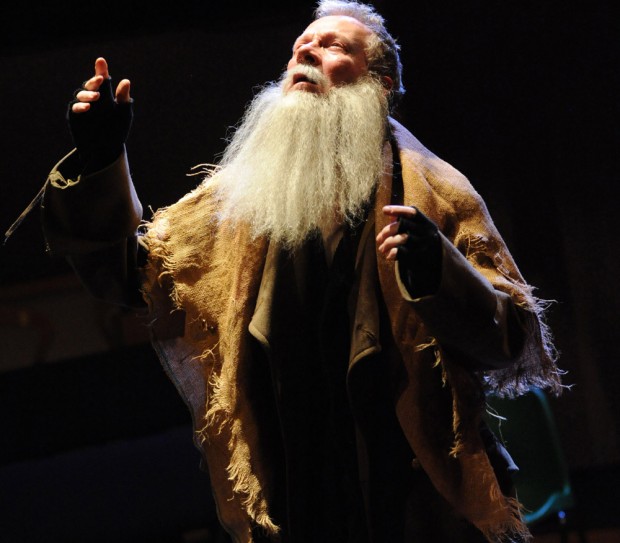

When Rudge, who might be a director, commentator or some other kind of creative, finally shows up, a method zooms into the madness. As an actor playing a hermit arrives, it transpires that these people are all gathered together to tell the story of Alexander James Mason, the Hermit of Great Canfield. In 1906, this real-life figure, at the age of 48, sold his Essex home and began to live as an isolated hermit, cut off by ditches, barbed wire and bee hives from the outside world, until his death aged 84.

Weird indeed. Of course, the actor playing the hermit wants Rudge to give him some motivation, and gradually, with much grumbling, he sinks his gums into the part. But before any of these theatre people can take very many steps down the path of narrative, they are smitten with more interruptions, digressions and philosophical speculations, some trivial, others more profound.

In Act II, Rudge presents a bravura account of grief, of creativity, of a lark ascending and a nightingale singing, and then moves on to playfully tell the story of the hermit’s conception. This monologue glances at the transient nature of sudden happiness and at the comic possibilities of a mosquito bite. Meanwhile, the actor playing the hermit keeps grumbling and begins to scratch his beard.

Lights go down, lights go up, and often the audience is bathed in light, complicit in this world of fiction and theatre and absurdity. Gradually, an encyclopedia of early 1960s preoccupations is revealed: existential ideas smudge into reminders of Ionesco; casual chat about the existence of God is torn into offcuts from Pirandello; social comment blends into the aburdism of NF Simpson. When the play was written, it clearly had a profound effect on Tom Stoppard: his 1966 debut, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead, has echoes of this play, and, come to think of it, his 1993 masterpiece Arcadia features a hermit.

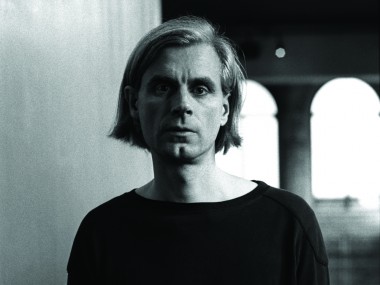

On a makeshift set, Anthony Clark’s clear and gently humorous production makes good sense of Saunders’s text and coaxes entertaining performances from his excellent cast: Aden Gillet’s commanding Rudge, Brendan Patricks’s cynical Dust, Roger Parkins’s jovial Meff, Jamie Newall’s cantankerous hermit and Holly Elmes’s charming Lizzie. Partly a meditation on theatre, partly a think-piece about death, partly a postmodern tease and partly a historical excursion, this is a weird and wonderful evening. With its confident satire and mock rhetoric, this play fully deserves to be rescued from obscurity.

This review first appeared on The Arts Desk