Pah-La, Royal Court

Monday 8th April 2019

Theatre can give a voice to the voiceless — but at what cost? Abhishek Majumdar, who debuted at the Royal Court in 2013 with The Djinns of Eidgah (about the fraught political situation in Kashmir), returns with his latest play, Pah-La. Just as his first one was controversial, his new effort is likewise politically sensitive. It is about Chinese oppression in Tibet, and its staging has been delayed for more than year due, says the playwright, to pressure from the Chinese authorities. Not only that, but the production process has been overshadowed by unhappiness about cultural appropriation since not a single Tibetan actor or creative has been included in the play. Still, the writer is supported by the Dalai Lama, so maybe we should overcome our anger with a Buddhist open-palm gesture, signifying generosity.

Based on real-life testimonies about the 2008 Lhasa riots, in which Tibetan locals attacked the property of Han Chinese and Hui Muslims, partly as a protest against poor economic conditions and partly as a blow against their country’s exploitation by Chinese minorities. It’s a highly contentious issue and Majumdar tackles it by focusing on two different individuals. In a Tibetan village, Deshar, a young runaway has disowned her father Tsering and become a Buddhist nun. Despite her training, she has a defiant attitude to authority figures. When the Chinese army decides to close down her nunnery, she commits a horrific act of resistance.

The authorities are led by Chinese Commander Deng, who operates from a prison in the regional capital Lhasa. But, as Deshar’s self-sacrificial act provokes riots and violence, Deng is confronted by his wife Jia, who is worried about the whereabouts of their daughter Liu. She has gone missing in the confusion of the rioting, and her parents are powerless to find her. Jia, angry at Deng’s inability to locate their daughter, decides to take matters into her own hands. So this is the story of two families — one Tibetan, the other Chinese — which are both put under intolerable pressure.

Pah-La means “father” in Tibetan, and the focus is mainly on Tsering and Deshar, and on Deng and his wife. Majumdar has an exuberant imagination and his play is a wild ride in which improbable incidents swerve luridly into view. If the constant switches of focus are often exciting, they can also be very confusing. You never know where the playwright will take us next. So expect the unexpected: there is a moment, a coup de théâtre, which can only be described as breathtakingly inflammatory, and a long and rather cruel torture scene which centres on an extended polygraph test. Occasionally, there are flashes of insight, but the piling up of detail also makes the piece’s message rather fuzzy. For a play about non-violence, I left with no clear view about what the story is actually saying.

For while the 2008 Lhasa riots form the background of the evening, the complex politics of Tibet take second place to passionate discussions about the ethics of resistance and the philosophy of non-violence. The trouble with most of these debates is that some of them have been written as Buddhist parables and all of them have a detached sensibility which feels oddly irrelevant despite the intensity of the anger portrayed. Everyday reality seems to have been given a rest, while the protagonists struggle with abstract ideas about mind and thought. By contrast, when a minor character, Deng’s assistant Ling, launches a heartfelt attack on fathers and the patriarchy, the stage is suddenly illuminated by a clear feminist intervention — what a relief!

The image of fire pervades this play, burning both humans and ideas. The distressing physical detail of injuries inflicted by setting petrol alight on a human body co-exist with evocative mentions of the Fire Sermon in a maze of intellectually and morally complex positions. There’s a strong sense of a humanist attitude to all belief systems, in which both the Buddha and the polygraph test are seen symbolically as twin gods. And if all fathers are really the major political problem of the world, it is clear that Chinese men are much more destructive than their Tibetan counterparts. When the playful stage action of the first half gives way to the much more emotionally fraught second half, the density and wordiness of the play increases.

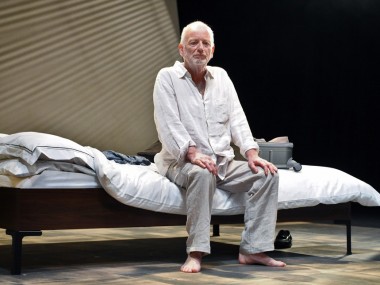

Despite the other-worldly discussions, Debbie Hannan’s production is thoroughly atmospheric and absorbing, especially at the start, which takes place in a Buddhist nunnery, evocatively designed by Lily Arnold in deep crimson and dark blue. Millicent Wong, making her UK debut, is outstanding as Deshar, a bright and punky youngster who is both highly intelligent and aware of her duty. By contrast, Daniel York Loh’s Deng is a frustrated patriarch who falls apart before our eyes in a horribly convincing way. Likewise, Richard Rees (Tsering), Tuyen Do (Jia), Gabby Wong (Ling) and Kwong Loke (who plays two contrasting roles) provide excellent support. But despite its intensity of feeling, the play is a bit too complex for its own good. Still, I do wonder what the People’s Daily reviewer would make of it all?

This review first appeared on The Arts Desk