Pressure, Park Theatre

Tuesday 3rd April 2018

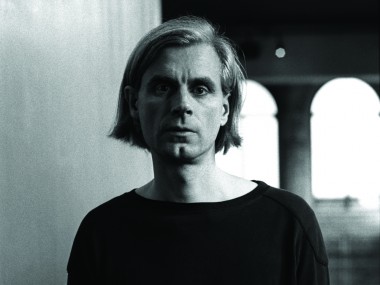

There are few things more British than talking about the weather. What makes this play about a meteorologist interesting, however, is its historical setting: the eve of D-Day, the Allied invasion of Nazi-occupied Europe. Although stories from the Second World War are hardly a rarity in contemporary British culture, this one is fascinatingly original and arrives at the Park Theatre after a national tour, having originally been seen at Edinburgh’s Royal Lyceum and Chichester in 2014. Already on its way to the West End, it is a huge personal triumph for actor and writer David Haig, who stars in the show that he wrote himself.

The story, based on real historical events, is a classic clash of views between the Brits and the Americans. In the days leading up to D-Day, the weather conditions for the most ambitious amphibious attack ever mounted are being closely studied. They have to be just right: the troops need to land in calm weather or their enterprise will flounder, and the war won’t be won. At Southwick House in Portsmouth, headquarters of the Allied army, the American General Eisenhower (Ike) is eager to give the go-ahead. It’s 2 June 1944 — time to give Hitler a bloody nose.

But Group Captain James Stagg, a dour depressive Scot who is the Allies’ chief meteorological officer, disagrees. According to his experience of the changeable weather of these isles a big storm is coming, and the Normandy landings will have to be postponed. But his view is not uncontested. Ike’s own man, Colonel Irving Krick — a confident American whose claim to fame is that he told MGM the best days to film the burning of Atlanta in the 1939 film classic Gone with the Wind — has the opposite opinion. He predicts clear skies and an easy Channel crossing. So who is right? After all, it matters. Hundreds of thousands of lives are at risk. As well as the outcome of the war.

Haig, who plays Stagg, also piles more pressure on his hero — and not just the atmospheric kind. His offstage wife Elizabeth is due to give birth to the couple’s second child, having narrowly survived complications at the birth of her first. She is in a nearby hospital: shouldn’t her husband join her? With enormous compassion, Haig weaves together a thrilling story that is both personal and political. Having done his research, he makes the gobbledygook of technical weather reports sound thrilling, and the arguments between the men convincingly clear. He also gives a compelling portrait of Stagg as a scientist who has a comprehensive practical approach, talking about seeing weather in “three dimensions”, but also so conscientious that he is uncertain as to what might happen in the future — after all, our weather is notoriously unreliable and erratic.

There is a touch of grandeur in this view of a scientist who is wracked with doubt. How can Stagg convince the military men, who desperately need to have certainty, that meteorology and predicting the future is inherently imprecise? At one point he tells Ike, “I can’t offer you certainty. I have always said that long-term forecasting is a gamble. What I do offer is twenty-five years of observing British weather.” This contradiction between the head (uncertainty) and the gut (certainty) powers the character, and makes this an unusually interesting documentary-drama. Pressure represents a very human dilemma: if everything I know tells me that one conclusion is the right one, why can’t I be 100 percent certain? It’s a tough one.

The play is distinguished by a couple of very strong set pieces — I particularly liked Ike’s speech about the costs of war — but although it is a good drama, it’s not perfect. It’s 20 minutes too long, and the ending has a couple of sad scenes that could easily have been cut. And the inclusion of the strand about Stagg’s wife feels a bit contrived, while the introduction of a female character, Kay Summersby, a young woman who is Ike’s driver and potential lover, also strikes a couple of false notes. War is a boys’ game so the attempt to feminise the men’s relationships feels anachronistic. Somewhere in the background, you can just hear the marketing department: what, no women? We must have female characters.

Nevertheless, as directed by John Dove on designer Colin Richmond’s office set, which is dominated by weather charts, Haig plays the gloomy Stagg with deep passion and a kind of obsessive energy. At one point he almost has a breakdown because of the stress, and his body vibrates and twitches with uncontrollable shakes. It’s clearly a star performance and it carries the show. I also rather rated Malcolm Sinclair’s Ike, a figure of great authority and charisma, as well as Laura Rogers’s sympathetic Kay and Philip Cairns’s confident Krick. The ensemble scenes are well managed and the most hectic passages give a good sense of the war being fought in real time. With its moments of comedy and atmosphere of high stakes, this is an excellent history play.

This review first appeared on The Arts Desk