Privacy, Donmar Warehouse

Tuesday 22nd April 2014

How careless are we about the details of our private life? Well, unsurprisingly the answer is “very”. To make this point, playwright James Graham explores the subject not only by means of verbatim testimonies from public figures, but also by involving the audience, taking a look at how members of the public leave a digital footprint on Facebook and Twitter, as well as the personal details we all share when we buy anything online — like theatre tickets. Oh, and yes, there’s also some dialogue.

When you buy a ticket for Privacy you get an automated email from Graham in which he says that “I’ll tell you a little bit about the show if you like but, please — sssh — it’s private”. With this comes an invitation to participate in the interactive part of the evening, with a list of Data Protection terms and conditions. Don’t worry, participation is not compulsory, but this email does its job: it puts you in the zone. It reminds you that we are all (almost) part of a world where the private is increasingly public.

Participatory theatre makes me nervous so I could feel my blood pressure rising as I approached the venue. On entering, I received a card which encourages me to keep my smart phone on. Phones will be used during the performance, which tells the story of The Writer (Joshua McGuire) and his research for a play about privacy in the digital age. He starts off by visiting Josh Cohen, a psychoanalyst and academic, and then discusses the project with The Director (Michelle Terry), who encourages him to experiment by going on a blind date.

When the blind date scenario is played out it involves a member of the audience (a plainly scared young woman who clearly regretted agreeing to participate). Such excruciating moments aside, the audience is taken on a lively ride up and down the information highway, with stops to meet stage versions of Graham’s long list of interviewees, who include Shami Chakrabarti and David Davis (whose real selves joined a host of other media celebrities in the audience on press night).

There’s some lovely moments of interaction with the audience, and a lot of hilarity. The serious issues — selfies, phone hacking, big data, online dating and spyware — are deftly discussed and imaginatively illustrated through some lovely projections. I particularly liked the evidence given for the thesis that data stored on the internet knows more about you, and sooner, than you do yourself. In the second half, there’s a brilliant retelling of the story of Romeo and Juliet and a more pedestrian account of Edward Snowden’s biggest leak of information in history.

But as the running time passes two and a half hours, the pace slackens. I know what is going wrong: Graham has done too much research (the programme not only has a huge list of interviewees, but also a bibliography!) and wants to use as much of it as he can. A lot of the material is well known (yes, I do know that my postcode will enable you to see what my street looks like), but some of it is pretty disturbing: the dead grandfather whose image remains on google earth; the adverts for pregnancy testing sent to a woman who was once pregnant, but doesn’t have kids.

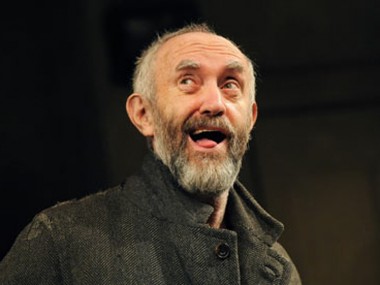

Josie Rourke’s production is designed by Lucy Osborne and aspires to be a total experience (the programme has been doctored to appear as if information has been redacted) and her cast is excellent: cheers to Paul Chahidi (Josh Cohen), Joshua McGuire, Michelle Terry, Nina Sosanya, Jonathan Coy and Gunnar Cauthery. Somehow, and despite a dizzyingly successful coup de théâtre (which the audience is pledged to keep private), the show lacks dramatic punch. And is this another example of soft socialism? Self-regarding and not as radical as it thinks it is? Probably…

More importantly, towards the end, I felt that Graham was struggling to find a metaphor strong enough to make sense of the huge amount of information radiating from the stage. He gives us glimpses of a nightmare vision of the internet running our lives, but my favourite image is the one in the programme: a little kid showing another infant a picture on his smart phone. There’s nothing quite so chilling, nor so charming, in the show itself. If the evening is too long, it is still an entertaining and often engrossing picture of a new world that mixes liberation with enslavement.

This review first appeared on The Arts Desk