Raz, Trafalgar Studios

Thursday 24th March 2016

Another week, another monologue. Another week, another agonised individual. And another refugee coming south from last year’s Edinburgh Festival. This time the playwright is Jim Cartwright, who, after writing the classic Road in 1986 and the equally brilliant The Rise and Fall of Little Voice with Jane Horrocks and Alison Steadman in 1992, has been a bit absent from the contemporary theatre scene. With only the odd exception, most of his plays have been well below par.

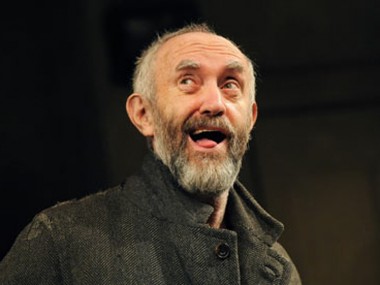

But now Cartwright’s back. And, what’s more his monologue Raz is performed by his son James, who plays Shane, a young low-paid worker on a booze-fuelled and high-octane night out somewhere in the North of England. Every Friday, it’s the same old story. Shane meets his mates, Staunton, Micksy, Sparky and Robo. Oh, and Tag, who tags along even when he’s being bullied and scorned. Out on the lash, or — in this case — the raz. The boys, and the girls they meet, get hammered, take drugs, have sex, turn violent, get legless, are sick and then crawl home, usually to the houses of their parents, which is the only place they can afford to live.

The show, like the night, starts off bathed in blue light with a quick nine-minute blast on the sun bed in the tanning shop. Then we’re in Shane’s bedroom as he gets dressed, first in his Superman briefs, while he poses in front of the mirror and orders some drugs from his dealer. Music pounds away, as he practises some moves and introduces us to his world. Although the night is predictable and the situation lamentably banal, Cartwright senior injects a touch of poetry into his descriptions that helps to lift the tale: the night “builds around ya really, like night black Lego, a thrill in every click”. At its best, the writing is reminiscent of Dylan Thomas’s Under Milk Wood. But only occasionally.

And the emotional heart of this brief story is Shane’s ex, a young woman who like a siren or spirit keeps crossing his path, not exactly beckoning, but constantly being the object of his memories and fantasies. At the same time, Shane can’t resist regaling us with his views on the behaviour of young men and women, which — he insists — has not changed since the Stone Age. According to him, primitive man did “prehistoric partying”, “blowing their brains on herbs” to “deafening drum beats” and “mad dancing”. Sadly, there’s something a little bit reactionary in seeing the history of the world as an unchanging party in which boys will be boys, and girls girls. It’s conservative bollocks, and there’s no-one in this monologue to contradict it.

Likewise, while it is evident that Shane’s loud bravado, with its boasts of drink and drug consumption, hides a much more vulnerable and unsettled psyche, a needy individual who needs tender loving, there is nothing here that shows how he might achieve any kind of healing. Instead, the lifestyle of glug, glug, glug, and snort, snort, snort, seems to have claimed him utterly and no tears will wash away his thraldom. His situation might be a strong image of the poverty, both material and spiritual, of today’s Generation Rent, but it hardly makes for a dramatic story.

Nevertheless, Cartwright junior has a very appealing stage presence, and Anthony Banks’s well-put-together production has him doing all his mates in different voices, as well as the squadrons of women and the bit parts such as the Welsh taxi driver. The use of jokes about Ant and Dec at the start of the show give it a seductively populist feel. With some help from Joshua Carr’s lighting and Ben and Max Ringham’s sound design, Cartwright the actor effortlessly and humorously dominates the stage and charmingly leads us through the events of the drink-spilled and vomit-spattered evening. But this slight show is barely 60 minutes long, and its content is too well-known and predictable to be either compelling or of more than passing interest.

This review first appeared on The Arts Desk