The Real Thing, Old Vic

Wednesday 21st April 2010

Tom Stoppard’s The Real Thing is a play about love, that most human of emotions, but neither the playwright, nor his main creation, can resist the temptation to be snobbishly inhuman. Originally staged in 1982, when it starred Felicity Kendal, the play became central to Stoppard’s life when the two of them fell for each other. Today, its mix of deep feeling, artistic eloquence and theatrical control retains its freshness, but its politics are pretty grim.

With more than a touch of autobiography, the play is about Henry, a classy playwright who betrays his wife, Charlotte, by having an affair with Annie, the spouse of his friend Max. The screw turns, if you’ll pardon the expression, when Annie — who works as an actress — becomes interesting in campaigning on behalf of Brodie, a soldier who has been locked up after having gone AWOL and then joining an anti-war demo. Recklessly, he has burned a wreath at the Cenotaph.

Despite Stoppard’s own support for artists in the former Eastern Bloc, he is deeply unsympathetic to political activism. His portrait of Brodie is as scornful as Henry’s view of the character. And it gets worse. While in prison, Brodie writes a political play. Of course, Henry is right to criticize the play that Brodie has written — he certainly is an appallingly clunky writer. But, on the face of it, there is really little to distinguish between Henry’s condescension, however charmingly expressed, and Stoppard’s. Both are clearly reactionary, snobbish, inhuman.

In Stoppardland, the men get the best lines — especially if they are artists or playwrights. Henry is no exception, but the play is much less generous to its women. Neither Charlotte nor Annie, nor even Henry’s teenage daughter Debbie, give as good as they get. All of them are represented as confused, flighty, emotional and unfaithful. Of course, you could argue that Stoppard doesn’t think that all women are like this, only these particular women. Or maybe not. Probably not.

Like love itself, many of the play’s ideas about love are ungraspable. When emotions are discussed, it often feels as if the characters are talking a foreign language, or that we are eavesdropping on a piece of music whose nature we know little about. But this lack of clarity is quite beguiling: it seems to suggest that the play is clever, and that we are being clever as we watch it. And behind the words there surely beats a heart that has experienced love, in its immense joy as well as its terrible pain.

Yet it is difficult to warm to this play, despite its undeniable wit and articulacy, because it is so obviously written from the point of view of a man with something to prove. Quite what Stoppard is trying to say isn’t clear, unless it is just that he seems to believe that men’s suffering somehow proves that they are feeling the “real thing”, and that women exist mainly to deceive and bring pain to men. But isn’t love meant to be about two people? This play is all about just one.

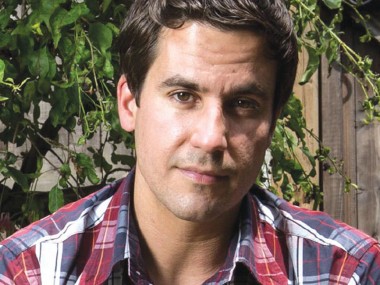

Anna Mackmin’s elegant and fast-moving production, on Lez Brotherston’s stylish set, has the undoubted benefit of a couple of great performances. Toby Stephens plays Henry with just the right mixture of lip-curling disdain and tear-sprouting emotion. Watching him felled by the doubts and jealousies of love, you can’t help but imagine that he’s truly feeling the emotions he’s portraying. Equally convincing is Hattie Morahan’s performance as Annie. Great acting, shame about the politics.

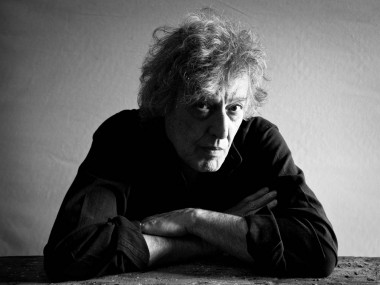

© Aleks Sierz