Red Bud, Royal Court

Wednesday 27th October 2010

American playwrights are hot this autumn. Wherever you look, their plays are colonizing our new writing theatres. Oddly enough, and Brett Neveu’s new play Red Bud is a perfect example of this, they are usually very short — not slices of life so much as a collection of crumbs. This is both good and bad: good because there’s no chance that they will bore you; bad because they never go beyond superficial impressions.

This play, which is set at an annual Michigan motocross championship, is 70 minutes long — just like Beau Willimon’s Lower Ninth and Annie Baker’s The Aliens. When a group of fortysomethings get together for this event, as they do every year, you know what kind of a play this Chicago kick-ass author is cooking up: yes, it’s a friendship-under-strain drama.

The friends are a cross-section of male failure. Jason is a joker who has lost his job, and his buddie Shane is a social worker who has been disciplined after the death of a child. Greg is a biker who has now laid up his helmet and is an expecting father — his wife Jen is heavily pregnant. They are joined by fireman Bill, who makes the other men jealous when he turns up with Jana, a 19-year-old girlfriend.

These red-blooded American men drink, smoke splifs, swear a lot, and play air guitar. And then play a drunken game which involves forfeits. But they are no longer boys, and the accumulated tensions of the past 20 years soon show that their friendship has some big cracks running through it. Greg is clearly dissatisfied with his lot, and he doesn’t seem happy with the prospect of fatherhood. Everyone seems to hate Bill, who dresses better than his buddies, and obviously has more pulling power.

Clearly, this play is a riff on American-style masculinity in crisis. The loss of work resonates with the condition of the United States at the moment, and none of the men is particularly sympathetic. But, on stage, the constant empty bravado soon starts to wear thin, and repeated yells of “Red Bud!” soon lose their appeal. We never really get enough information on what ails these men specifically, so it is difficult to empathise.

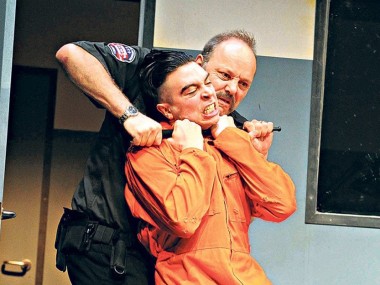

I could just about accept the final explosion of violence, but I wasn’t convinced that Neveu really had much of interest to say about the compromises of middle-age, or about the protracted adolescence that is part of these men’s make-up, and part of the consumer marketing at the heart of the American Dream. If these men are unhappy because they can’t fulfill the market’s dream of lifelong youth, too bad — but as a metaphor for a whole continent it was a bit thin.

Jo McInnes’s highly naturalistic production has a design by Tom Hadley that covers the studio theatre with grass, small tents and a smouldering open fire. Trevor White plays Bill with an open countenance that turns into a slack-jaw gaze whenever Isabel Ellison’s flirtatious and unpredictable Jana comes into range. But most threatening of all is Peter McDonald as Greg, who turns out to be the most repressed and most self-destructive, while Lisa Palfrey works hard to make his appalled wife believable. Hywel Simons as Jason and Roger Evans as Shane, both victims of economic forces they can’t quite comprehend, produce a nice mix of clowning and misery. But despite some hot directing, and committed performances from the whole cast, this never rises above being a single episode of a broader story that is detached from the bigger picture. It all feels too easy, too plain and too uninspired.

© Aleks Sierz