The River Line, Jermyn Street Theatre

Thursday 6th October 2011

London fringe theatre excels at disinterring forgotten plays, brushing the soil off them and displaying them for our inspection. Like the trendsetting Finborough Theatre, the Jermyn Street Theatre — run by Gene David Kirk — has had a good couple of years recently and its latest excavation is The River Line, a 1952 play by Charles Morgan, who in the 1930s was a novelist and drama critic of The Times. The play has not only been forgotten, but doesn’t even merit a footnote in the standard histories of post-war British theatre. Based on Morgan’s 1947 novel of the same name, it starts in the immediate aftermath of the Second World War, welcoming us into the garden of the Wyburtons’ house in Gloucestershire on a hot July day.

Julian and his French wife Marie are survivors. During the war, she was part of a network — The River Line — dedicated to spiriting shot-down Allied airmen and prisoner of war escapees across Occupied France and into neutral Spain. He was a British intelligence officer in the field. Staying at their country house is Philip, an American ex-serviceman who first met his hosts during a dangerous escape in the war. He has fallen for Valerie, their god-daughter, and wants to marry her. But before he does, he needs to tell her about his wartime experiences and one incident when the escapees had to kill a German spy who had infiltrated the Resistance network.

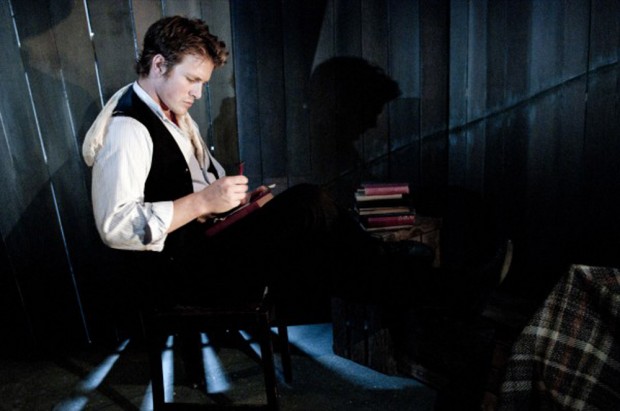

So, in Act Two, there is a flashback to the war, when Marie hid and looked after Philip, Julian and a couple of other Allied servicemen in a granary deep in rural France. In a thrilling piece of storytelling, Morgan shows how the men’s fears, tensions and mutual suspicions result in the death of Heron, one of their number. He then asks the question: what if their victim was innocent?

Morgan’s play is partly a study of intellectual ideas, partly a wartime thriller and partly a social comedy. Sadly, he can’t resist complicating his material by adding various metaphysical and religious ideas to what could have been a simple story of guilt, confession and forgiveness. The fact that these ideas now seem dreadfully convoluted and old-fashioned explains why his play is so rarely performed.

The story’s strengths are its plot, its humour and its portrait of Englishness. Not only are these Englishmen, with their stiff upper lips, well contrasted with the essentially optimist Philip, but the culture of secrecy pervades the play. In this 1940s England, the stiff upper lip must remain buttoned tight no matter what. But while there is now something charmingly nostalgic about an England where one’s word was still one’s bond, what really struck me was a speech by Marie in which she has a startling vision of a third world war. This shocking reminder of Cold War fears is a highpoint in a play weighed down by its literary writing style and gnarled morality.

Efficiently directed by Anthony Biggs, the cast has two twin (literally!) stars, neither of them at all convincing. The Twilight saga’s Charlie Bewley plays Heron with such restraint we can barely identify with him, while Lydia Rose Bewley from The Inbetweeners Movie is too heavy for Valerie’s fastidious Englishness. Much better are Christopher Fulford and Lynne Renee as Julian and Marie; Edmund Kingsley perfectly catches Philip’s breezy openness.

So although there is much to admire in the plotting and the passionate intensity of some parts of Morgan’s play, this revival also rams home once again the point that the new drama brought in by John Osborne’s Look Back in Anger in 1956 blew away all kinds of cobwebs from the British post-war theatre. One of its victims was the earnest moral drama such as The River Line. I can’t honestly say that this fate was completely undeserved.

© Aleks Sierz