Rock ’N’ Roll, Hampstead Theatre

Friday 15th December 2023

There is a song by Syd Barrett, founder member of Pink Floyd, called “Golden Hair”. It’s on his solo album The Madcap Laughs, released in 1970, a couple of years after he left the band, and every time I hear it I feel like I’m falling in love again. With the song, with him, with pop music. It also features in Tom Stoppard’s 2006 epic, the aptly named Rock ’N’ Roll, now revived at the Hampstead Theatre by playwright and director Nina Raine. The figure of Barrett — an antic madcap whose use of LSD both inspired his psychedelic music and destroyed his mind — runs, skips and somersaults through the play, which spans European Cold War history over some 20 years between 1968 and 1990.

The play opens in Cambridge, at the home of Max, a Marxist who continues to support the Soviet Union despite Stalin and the crushing of the Hungarian revolution of 1956, and his wife, classics professor Eleanor. As Eleanor teaches the poetry of Sappho, she is also fighting cancer. The main story concerns Max’s relationship with Jan, a philosophy student from Czechoslovakia. Galvanised by news of the Prague Spring and Soviet invasion of his homeland, Jan is about to return, and argues with Max, who thinks that the communist states should follow the Moscow line. Before he goes, Jan catches a glimpse of 16-year-old Esme, the daughter of the house, a flower child entranced by Syd Barrett’s resemblance to the Great God Pan.

Back in Prague, Jan finds himself in the middle of the dilemma of the reformists: how much can you protest against a dictatorial regime before you end up in jail? As he refuses to sign various petitions, preferring instead to listen to rock music albums –— lots of fab riffs from the Beatles, Rolling Stones, Beach Boys, Velvet Underground, Fugs and so on — he is gradually drawn into the ambit of the Plastic People of the Universe. He sees in this local Czech rock band an attitude of defiance which involves a withdrawal from public politics into a more subjective realm. A place where the most radical thing to do is to pursue your own sense of pleasure. Freedom from censorship.

While things turn out to be difficult for both Jan and the Plastics, the second half of the play returns to Cambridge. It is summer 1987, and, to Max’s chagrin, Mikhail Gorbachev is leading the Soviet Union along the road of perestroika. As Max’s health deteriorates, his daughter Esme, and student granddaughter Alice, hold a lunch party which brings most of the story’s characters — including Esme’s estranged husband Nigel and the Czech intellectual Lenka — together again. During more discussion of Marxist politics, tabloid journalism (a vulgarly populist article about Barrett has been written by one of the other guests), and the state of the nation, Jan also appears. It turns out that he loves not only English rock music, but one English woman too.

Stoppard’s play is baggy and full of talk, not only about whether communist regimes can be reformed or just passively resisted, but also about Sappho and love. If sexual desire is a thing of both mind and body, as Eleanor argues, then so is disease, which affects your mental state as well as your physical condition. In this human complexity surely Max’s materialism, however well expressed, is an inadequate theory. At the same time, Jan’s immersion in rock music feeds, at one and the same time, his desire for glorious transcendence and his social isolation. Amid some great word play and comedy complex issues about the nature of consciousness and the truth of personal betrayal wave at us from a parade of history that is intensely compelling.

Stoppard is a very literary playwright — just look at his 1966 debut Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead or his 1993 masterpiece Arcadia — and a note in his playtext for Rock ’N’ Roll explains how Barrett’s “Golden Hair” is based on a poem by James Joyce — who of course featured in Stoppard’s 1974 play Travesties. Ever punctilious, Stoppard includes the detail that Barrett added a line to Joyce’s original and thanks the Irish writer’s estate for their forbearance. But although such cerebral literary material is typical of this playwright, in this family drama there is also a strong emotional pull, partly deriving from the fact that since Stoppard was himself born in pre-war Czechoslovakia, his Jan character is a kind of invented parallel autobiography.

The central theme of personal freedom, which often looks different depending on which system you live under, remains strong although the play does have greater resonance for the over 60s than the under 30s. There is a clear contrast here between the East’s dictatorship, where young people who don’t want to conform are forced to choose between martyr-like public dissidence and secret hedonistic pleasure, and the West’s democracy of obedience, of repressive tolerance, in which civil liberties have drained away, and where a culture of celebrity gossip and rampant consumerism trumps reform. Stoppard offers the Charter 77 movement as one Czech solution, and suggests that pop culture can bring East and West together in a dream of ecstasy.

This is all well and good, but Raine’s rather disappointing production seems to have put so much energy into creating a traverse staging — similar to that of her big 2011 success Tiger Country — that not enough work has been done either on the individual acting or the ensemble. The lunch in Act Two is notably slack and unfocused, signifying a weak directorial grip unable to cover the problems caused by Stoppard’s occasionally erratic storytelling and lack of clarity: in the end, who has betrayed who? The final showdown between Max and Jan remains unclear. On the plus side, Raine’s smash cuts between each scene, which feature loud rock music and bacchanalian freak dancing, are thoroughly thrilling, a great reminder of the cultural and personal power of rock to redefine our sense of joy.

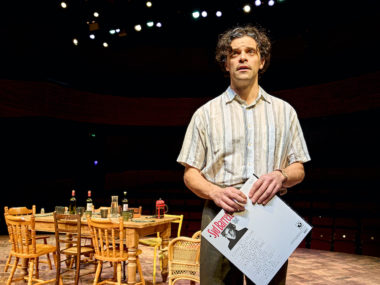

As for the acting, Nathaniel Parker holds the play together with his mixture of opinionated anger and occasional moments of softer emotion. As both Eleanor and Esme, Nancy Carroll does not really — in my eyes at least — distinguish sharply enough between mother and daughter, which gives her performance a sameness over the 2 hours and 45 minutes of running time. Jacob Fortune-Lloyd lends Jan a nice hangdog expression, but lacks charism and vitality. In the smaller roles, I like Colin Tierney, who plays Milan and other Czechs, and Hasan Dixon as Ferdinand, Jan’s Prague friend. Brenock O’Connor’s Piper at the Gates of Dawn adds a touch of addled hippiedom. Still, the play continues to fascinate: come on oldies, let’s rock again!

This review first appeared on The Arts Desk