Small Island, National Theatre

Wednesday 1st May 2019

Novelist Andrea Levy’s 2004 masterpiece, Small Island, is a tribute to the Windrush Generation, those migrants to England from the Caribbean that came first on the HMT Empire Windrush in 1948, and then subsequently on other ships. Being British citizens by right, the discrimination that they faced in the postwar years, which culminated in the 2018 Windrush Scandal, when so many of them have been denied their legal and human rights, is a stain on recent history. So it feels right that the flagship National Theatre should honour their lives and experiences, however belatedly.

Sad to say, Levy died in February at the age of 62, before rehearsals began for this stage adaptation of her novel by Helen Edmundson. Unlike the book, this version focuses mainly on Hortense, a shy light-skinned girl who grows up in Jamaica in the 1930s, in the home of her cousin Michael, a confident boy who becomes a rebellious young intellectual when he returns from boarding school. But while he contests his father’s strict religiosity, she remains moralistic and rather repressed. Although they are childhood sweethearts, they never become young lovers.

When the second world war breaks out, Michael travels to England to enlist, as does another well-educated young man, Gilbert, who dreams of becoming a lawyer. In London, they stay at the house of Queenie, who has come to London from her parents’ pig farm in Lincolnshire, and lives with her cold, racist husband Bernard. When Bernard enlists, she begins to let rooms to servicemen, and doesn’t care about their skin colour. Back in Jamaica, Hortense meanwhile becomes a school teacher. At the end of the war, Gilbert returns to the Caribbean, meets Hortense and brings her over to London as his wife. Trouble erupts when, after many years, Bernard finally comes home.

The story has an epic scope and symbolizes the experiences of a whole generation of Jamaican migrants. Levy based it on the lives of her parents and their friends, and much of the story is familiar: the terrible gap between the illusions of Jamaicans about the attractions of the Mother Country and the realities of British postwar racism; the degrading living conditions and poor jobs that educated and professional black people had to accept; the brutality of English prejudices. Of particular interest is the fact that so many young black men enlisted in the RAF, and helped the British war effort in many other ways, rather than staying in Jamaica and fighting for that small island’s independence (finally achieved in 1962).

Although this production, which is directed by the National’s artistic director Rufus Norris, is full of good intentions, isn’t it a bit odd that most of the creatives behind the adaptation are white? With a white playwright and a white director, the message seems to be that there are no black playwrights and no black directors who could lead this project. And isn’t it a bit patronizing that the overall tone of the production relies heavily on buffoonish comedy and rather clichéd situations? The adaptation itself is a worthy version of the novel, but it has been smoothed out and the storytelling is rather pedestrian. Oh, and the evening lasts for three hours and a quarter.

Norris directs a diverse cast of some 40 actors, some of whom are supernumeraries. He controls the crowd scenes well on the merciless Olivier stage and the production strikes a good balance between the epic, helped by Jon Driscoll’s massive projections, and the more intimate moments. Katrina Lindsay’s set is simple and highly mobile so the pace of the show is good. Highlights, such as the arrival of the Windrush and a Caribbean hurricane, are suitably impressive, and Norris adds many humorous visual jokes, often involving stage machinery and traps. Despite the fun, and there is a lot of it, some issues feel underdeveloped: Levy stresses the importance of lighter skin colour and although this is mentioned it is not explored as much as it could be.

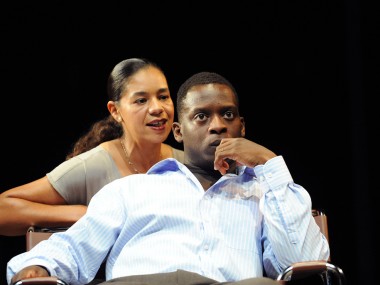

Edmundson’s version gives the characters plenty of opportunities to address the audience directly, and this creates some empathy. Although the tale is rather plodding, the characterization is vivid if a touch stereotyped, especially in the numerous comic moments. Still, there’s a lot of enjoy in Leah Harvey’s performance as Hortense, a young woman whose dignity is threatened by poverty and whose naivety is overcome by experience (the excruciating childbirth scene, which mixes comedy with boggle-eyed amazement, is a highpoint). As Queenie, Aisling Loftus has a winning working-class charm, while Gershwyn Eustache Jnr’s Gilbert is thrillingly convincing. Equally impressive are CJ Beckford as Michael and Andrew Rothney as Bernard.

Small Island is overlong, and takes most of its considerable running time to warm up. If it does deliver some heartbreaking moments, and finally becomes genuinely moving towards the story’s climax, this is mainly down to the acting of Harvey, Loftus and Eustache Jnr, who very gradually allow us access to their hearts. But while it is right that we should be ashamed of the history of overt racism in Britain, and respect the endeavours of those who migrated to make a new life for themselves, it’s a shame that this adaptation is so traditional, so unimaginative, so banal. On the other hand, it’s hard to deny that the production is big, bold and spectacular, as well as accessible, relevant and fulsomely entertaining.

This review first appeared on The Arts Desk