Table, National Theatre

Friday 12th April 2013

The family can be a knot of hatred as well as a cradle of love. Rather late in this new play by Tanya Ronder comes a scene in which a separated husband and wife try to untangle this knot, and end up by tightening it. And this takes place around a table, which is silent witness to this epic tale which spans more than a century, and uses nine actors to create some 23 participants over six generations.

By a happy coincidence, this story of a wooden table takes place in the Shed, a new wooden theatre which the National Theatre has built in its riverside front yard as a temporary space while its Cottesloe stage is being redeveloped, part of a £70million project. The smell of wood hangs lightly in this new 225-seat venue, which is painted bright red, and has a cool intimacy.

Table tells the story of the Best family from a new marriage in Lichfield in 1898, through the First World War to a missionary outpost in 1950s Tanganyika, then to a hippy commune in late 1960s Herefordshire, ending up in South London today. Ronder has fragmented the story by shuffling events out of sequence and this tricksy move partly disguises some of the thinness of the events depicted.

The central character is Gideon, the son born of a short liaison between a big-game hunter and a nun, and who grows up first in Africa, and then in an English hippie commune (the excuse for a funny scene, which however is yet another instance of 1960s-bashing worthy of the late Mrs Thatcher). Out of this experiment in free love, Gideon finds Michelle, who he marries, and then abandons, along with his son. The pain of being fatherless and the loss of children is a constant theme.

As the story slowly builds up, the table is the centre of banal family rituals (meals of course) and gradually becomes a place where couples have sex, where children play and where a corpse is laid out. A leopard is shot, a spider is uncovered, missionaries confront their problems, people etch their initials in the wood. Around this piece of domestic furniture hymns are sung, folksy songs are hummed and pop tunes are performed.

The table is not only an everyday object but also a symbol of family history. It is both an object of craft and care and a body scarred by experience and the blows of life. Like a diary hewn in wood, it is a simple thing which has complex resonances. It is also the centrepiece of this production by Rufus Norris (London Road, Doctor Dee — and Ronder’s husband) who directs with sinewy sincerity. At one point, the table stands bare except for a small vase of wild flowers: illuminated by a blaze of light, it is an image of deep emotion.

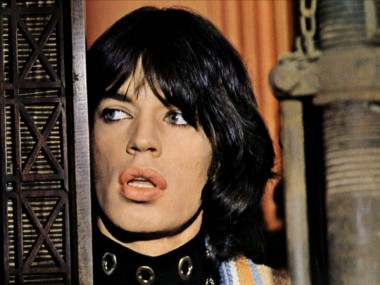

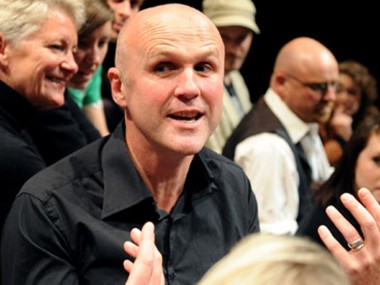

Like this beautifully crafted table, the play also has attractive features and generally harmonious proportions. Ronder’s writing is well crafted and the play is nicely polished and solid. At the same time, the story is very complex and not always clear. Many incidents just don’t gel, and — despite some enjoyable scenes — the evening lacks a decisive point. Of the cast of nine, Paul Hilton is particularly impressive as the passionate Gideon, and he is ably balanced by the quieter steel of Rosalie Craig as his mother Sarah and Penny Layden as his truth-telling wife Michelle. The feelings of broken lives, terrible loss and sadness stick out like splinters in an evening which shows how family life rarely runs smooth.

This review first appeared on The Arts Desk