Talking About the Fire, Royal Court

Friday 8th December 2023

Let’s start with what we know: the climate emergency is the single most burning question facing the planet. Our life on Earth depends on tackling it. Right? Well, maybe not, argues theatre-maker Chris Thorpe in his new one-man show, Talking About the Fire, currently enjoying a short run at the Royal Court theatre. Instead, he proposes the proliferation of nuclear weapons as the single most dangerous issue threatening our lives today. And he has a point: there are very few humans who have lived in a world before the creation of the Bomb — it has been there all of our lives. But what can we do about it?

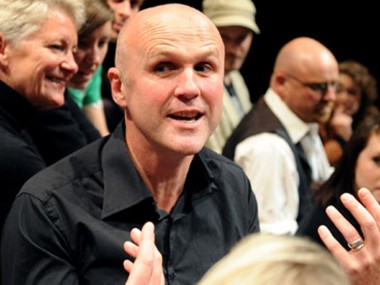

Thorpe’s show, an introductory lecture on nuclear disarmament, begins as the audience files into the intimate upstairs studio at this venue. He makes a point of greeting every one of us, saying hello to his friends, giving everybody a warm and slightly sheepish smile, learning our names, asking how we are. Then, after the usher takes their seat, he segues into the performance: asking a member of the audience for the name of a song, finding it on Spotify and then starting with a cool, slow semi-rap. Soon he’s onto the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, a 2017 UN intervention which makes it illegal for signatories to develop or keep a nuclear arsenal.

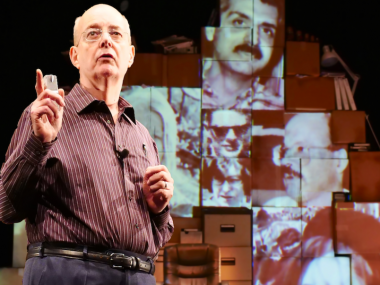

Of course, only about half the countries in the world have so far signed this ban on the Bomb, and none of the nine nuclear powers. As Thorpe outlines the history of nuclear weapons he personalizes this by talking about his meetings with Veronique Christory, Senior Arms Control Adviser for the International Committee of the Red Cross and the UN, who helped negotiate and now promotes the ban. As an illustration of the devastating power of these weapons he shows us YouTube footage of the 2020 Beirut port explosion, which is devastating, but has only a fraction of the force of a nuke. Looking at a Google Nukemap (yes, this is a thing!), he shows us the effects of dropping a bomb on the Royal Court. Horrific for all of London.

Throughout the 80 minutes of the show, which includes chat about his Manchester roots, Thorpe is a very engaging and humane presence, likeable and charming, taking care to involve everybody in the discussion. Some bits are like a pub quiz, with biscuit treats circulating around the audience; some bits are like a friendly seminar; some bits have music, others rely on projections. It feels intimate and audience friendly, even asking us to collectively imagine a safe space for the discussion of the effects of nuclear war, and then showing how such a conflict could break out, whether in Ukraine or Gaza. It’s sobering, serious and — in a good sense — educational.

Much as I like this piece, which in a mild way does play a small part in redefining what today’s activist theatre might be (affable, chatty and slightly inconsequential), there is very little of the wayward imaginative writing that characterizes Thorpe’s other work, say The Shape of the Pain or Victory Condition. An older generation, who remember the glory days of the CND and Greenham Common, might find most of the show as familiar as the Turkish rug on which the chair, table, laptop and keyboard are positioned. A younger generation might be appalled to discover another reason for despair. Most people will leave the venue heartened by Thorpe’s call to do something (details contained on a card which we get given as we exit).

The leisurely pace of the show is relaxing, even if the material is bleak, with Thorpe’s conversational style being low-key and informative, a bit slack but also deeply sincere. There are moments of comic relief too. The design by Eleanor Field has a homely feel, like we’re in Thorpe’s living room and his taking of a cup of tea near the end of the piece feels very English. Co-creatives include Malaprop director Claire O’Reilly and Tony-Award-winning director Rachel Chavkin in a co-production by China Plate and Staatstheater Mainz. Arnim Friess’s lighting is good at disturbing audience complacency, making sure we can’t snuggly hide in the dark. The result is both participatory and quietly urgent.

This review first appeared on The Arts Desk