The Blinding Light, Jermyn Street Theatre

Tuesday 12th September 2017

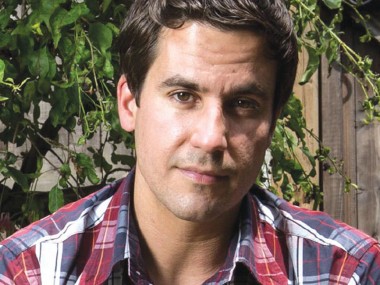

Anyone who likes playing “Spot the weirdo” will find themselves instantly at home in Howard Brenton’s new play, which has its world premiere in this West End fringe venue, a stone’s throw from Piccadilly Circus. Its subject is Swedish playwright and writer August Strindberg, and the psychological crisis which he suffered while living in Paris in 1896. He documented this experience of breakdown and hallucination in his autobiographical novel, Inferno, written in fury while he was experiencing paranoia and other delusions. Helping Brenton make sense of Strindberg’s plight is Jasper Britton, a very personable actor who plays the main role in this 90-minute account of a life less ordinary.

At the time, Strindberg was already a celebrated playwright, having enjoyed huge success with Miss Julie and The Father, but he suddenly decided to abandon the theatre and take up alchemy instead, attempting with scant success to turn base metal into gold. Not that that put him off. Although his account in Inferno is very exaggerated, it does make a compelling and even chilling story. Holed up in the Hotel Orfila in the Rue d’Assas, the celebrity creative goes crazy, performing bonkers alchemical experiments in the bathroom, which starts to pong alarmingly, while imagining that his first two wives, Siri and Frida, are laughing at him, and having lengthy conversations with each in turn. Then there’s Lola, a chambermaid, a figment of his imagination — or a premonition of the future?

Brenton charts Strindberg’s psychotic episode with enormous flair in a compelling and at times hilarious play. The early minutes, when Lola attempts to clean up the playwright’s room, are very funny, and Britton’s troubled playwright oozes charm as well as mania. Gradually, his voice rises into a squeak as he gets het up, and his madness has a comic side along with a sad one. Later, when he is admonished by his wives, he shrinks into a little schoolboy figure, sitting meekly when he’s not remonstrating with them. Brenton has done his research but it is never obtrusive and the play works as a biographical piece, told through the delusions and memories of an artist who is having a breakdown.

Brenton’s Strindberg has a lot of good lines, from his paradoxical understanding of alchemy (“The more imaginary the gold the more we believe in it”) to his defence of his early, and radical, naturalistic style in theatre, which involved real cooking on stage (“the kidneys were revolutionary”). The scene with Siri has a genuine tang of reality as their imaginary conversation jumps from fond memories to recriminations, often in mid-sentence, while Strindberg’s interaction with the younger Frida is less deep, skimming more lightly over the couple’s emotions. Both evoke the world of theatre in Stockholm and Berlin, with its cafés, its rivalries and its triumphs.

That said, Strindberg is not an easy character to hang out with. Even in his saner years. Trapped in a room with this arch woman-hater, impossible egoist and deluded radical at the height of his mania can feel like a bit of a trial, and it says much about Brenton’s playwriting abilities that this piece does not seem overlong. As Britton paces the floor, drinking absinthe (a devilish drink if ever there was one), hearing voices and imagining people coming out of the walls, you begin to long for the sunlight of everyday life rather than the smelly hell of bohemian excess. And that’s what makes the passages in which the working-class Lola confronts the cracked artist so witty and enjoyable: she blasts him with her common sense.

The Blinding Light is a fascinatingly febrile dream play, commissioned and directed with a passion for detail by Tom Littler, this venue’s new artistic director, on Cherry Truluck’s set, painted in a sickly mix of gold and primary blotches, lit by William Reynolds and with Max Pappenheim’s music. Joining Britton, whose paranoid, suspicious and anti-feminist playwright never leaves the stage, are Susannah Harker as the maternal, matriarchal and magisterial Siri, Gala Gordon as the posher Frida and Laura Morgan as the amusingly down-to-earth Lola. Brenton’s play intriguing compares Strindberg’s psychological collapse with the self-experiments that alchemy demanded of its acolytes. And he convincingly suggests that, after this experience, the playwright emerged stronger and more creative. A sympathetic portrait of a true weirdo: a blinder.

This review first appeared on The Arts Desk