The Bomb: A Partial History, Tricycle Theatre

Sunday 19th February 2012

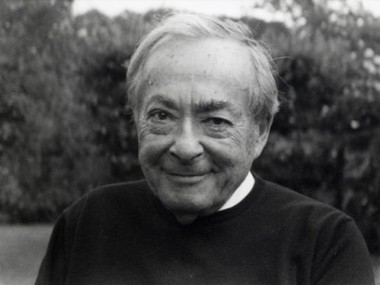

The bomb has cast a long shadow over the globe since its horrific use at Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945. Coincidentally, this was also the year of birth of Nicolas Kent, the artistic director of the Tricycle Theatre in north London, who is standing down in protest against Arts Council funding cuts after 28 years in the job. During that time, he has vigorously advanced a political agenda and an ambitious vision, pioneering verbatim drama and plays that engaged with the new world order after the fall of the Berlin Wall.

This political insight and theatrical flair is exemplified by his final project, The Bomb: A Partial History, which comprises two parts of five short plays each, and tells the story of nuclear weapons proliferation from 1945 until the present day. You can see each part — both of which last about two and a half hours — on consecutive evenings, or both during a single day, mainly at weekends.

Part One, called First Blast: Proliferation, begins with two German Jewish scientists bringing news of the possibility of nuclear fission to Whitehall in 1940, only to find that the Brits are almost too rigid and bureaucratic to take any notice. This is followed by Clement Attlee discussing the policy of an independent nuclear deterrent in 1945 with Ernest Bevin, American Secretary of State James Byrnes, scientist William Penney and Field Marshall Grierson. Written by Zinnie Harris and Ron Hutchinson, these two opening shorts — called The Message and Calculated Risk — are exciting in the density of their ideas and the clarity of their allusive metaphors. The bomb appeals to politicians because it is evidence of a virile and important nation.

Less impressive is Lee Blessing’s Seven Joys, a potted history of arms proliferation staged in the location of an exclusive club that gradually acquires new members from Russia, China and the Indian subcontinent. Similarly, Amit Gupta’s Option is an account of debates within Indian society in 1968, in which the pursuit of a nuclear bomb clashes with Gandhi’s theory of non-violence, and is thus a question of national identity. To make a bomb may affront this legacy, but it also proves that India is a top scientific country. As a way of escaping the contradiction between aggression and peacefulness, the answer is to develop a “peaceful nuclear explosion”.

The most fully imagined of the First Blast plays is John Donnelly’s Little Russians, which is set in the Ukraine in 1993. Here, Yuri and Andrei, two local youths, attempt to sell an ex-Soviet nuclear missile to the Chechens, using a Russian ex-army officer, Vladimir, as a go-between. The tone is acidly comic and the writing is lively enough to raise the spirits. By giving the Ukrainians an Irish accent, Donnelly sets up a series of resonances about the relationships between Empire and periphery which go beyond the ostensible subject of the playlet.

Looking back at this First Blast, there are some awkward gaps: nothing on the Japanese reaction to being bombed in 1945, nothing on the Cuban missile crisis, nothing on other dangerous crises, or nuclear accidents. Nothing on The War Game. China remains a mystery, and, on its own, the play about India feels a bit exposed. Arms reduction gets only a passing mention. This is, indeed, as the season’s subtitle admits, a very partial history of the bomb.

But Part Two, Present Dangers, feels more coherent, and relevant. The current dangers of nuclear weapons in Pakistan, North Korean and (perhaps soon) in Iran, have focused the minds of the playwrights. Particularly impressive is Colin Teevan’s There Was a Man, There Was No Man, about the assassination of an Iranian nuclear scientist. It plays intriguing mind games with the question of who did it: Mossad or the Iranian Secret Service?

Likewise, Ryan Craig’s Talk Talk Fight Fight (title taken from Mao Zedong) looks at the relationship between the US and Iran with enormous verve and confidence. It examines a diplomatic game of double-cross and double-double-cross between the two countries with a kind of grim humour that says a lot about cultural misunderstanding, as well as about international power politics.

But the best play of the entire season, and the only one that really captures the sheer madness of nuclear war is David Greig’s The Letter of Last Resort. This is the document that each incoming prime minister has to draft for the commander of our nuclear submarine to be opened in the event of the UK being annihilated in an atomic attack. Greig’s Kafkaesque text is hilarious and brilliant. Played as a dialogue between two characters, a future female Labour prime minister and a civil servant, this is a heady and inspiring satire.

Inevitably, some of the 10 plays work better than others. The final short, which echoes the opening play, felt unnecessary, but the general aim of the project, to relight a debate about Trident missile system that seems to have become dormant, is just right. The argument that senior figures in the British military don’t want Trident could do with some filling out, but the issue of nuclear weapons is clearly one that won’t go away. Kent’s directing and Polly Sullivan’s design are laudable, and the 11-strong cast — which includes Simon Chandler, Belinda Lang, Nathalie Armin and Paul Bhattacharjee — delivers the goods. As well as these playlets, both parts of The Bomb have short verbatim moments, and the whole season includes discussions and films. All in all, this is an ambitious but urgent piece of political theatre. And a suitable farewell gesture from Kent.

© Aleks Sierz