The Dresser, Duke of York’s Theatre

Thursday 13th October 2016

The best way to line up the stars is to offer them a part in a play about the theatre. For this, Ronald Harwood’s The Dresser has a reasonably good track record: its original West End outing starred Tom Courtenay; the 1983 film version had Albert Finney and Courtenay again; and a 2015 BBC television version had Sirs Anthony Hopkins and Ian McKellen. Now it’s the turn of Ken Stott and Reece Shearsmith to enthrall audiences in this account of theatrical backstage life, which first took up West End residence in 1980.

Harwood worked as a dresser to Donald Wolfit, the mountainously idiosyncratic Shakespearean actor-manager who died in 1968, although it would be a mistake to see this drama as a straight biography. Rather it is more like a fantasia, a love letter to a lost world where independent theatre companies, often third-rate and full of eccentrics and failures, toured the land, bringing the bard to the masses. Harwood sets The Dresser during wartime when the national emergency meant that most able-bodied actors were conscripted into the army so the companies had to recruit whoever else was available. As morale-boosters, even ham actors and assorted incompetents could contribute to the Home Front.

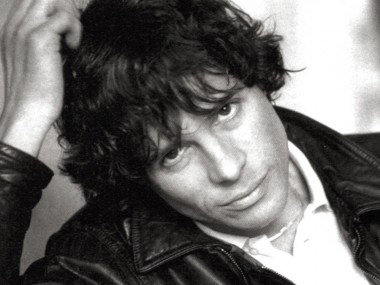

During the first scene, set in Sir’s dressing room, we see how the dresser Norman (Shearsmith) tries desperately to get Sir (Stott) ready for the evening performance of King Lear. This is an uphill task because the great, if prematurely aged, actor-manager is suffered an extreme fit of stage-fright mixed with dementia and exhaustion and melancholy and who knows what else. Stott weeps, wails and stares around himself with an expression of acute bewilderment. Surely, say his wife — dubbed Her ladyship — and his stage manager Madge — a devoted spinster — he is no condition to go on? But Norman insists that Sir is okay, and helps him prepare his make-up, his wig and reminds him of his lines.

Then the curtain of this fictional provincial venue rises, and so does the anxiety as King Lear begins, during an air raid of course, with Sir insisting that the show must go on. Will this veteran of more than 220 performances of this quintessential tragedy get through the night? Harwood provides a crowd-pleasing answer, and then goes on to explore life backstage in more detail, showing how Her Ladyship has suffered neglect by her monstrously selfish husband, while Madge has also been exploited mercilessly. Irene, an aspiring young actress, is introduced for no very good reason except to show us the obvious: Sir likes to fondle nubile women. But although the play has a certain charm as a heartfelt evocation of Wolfitdom, Harwood never really manages to convince me that the crisis experienced by Sir is anything more than a crude device to rack up the tension.

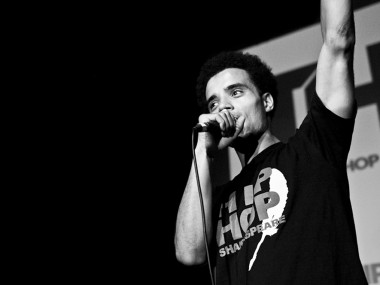

Sean Foley’s production, however, is finely directed and an apt celebration of the playwright’s 50-year career. Stott’s actor-manager is particularly commanding, his gravelly voice rising to a boom, the actorly consonants and vowels rolling around like waves beating against the shore, often giving the Luftwaffe’s thundering bombs a good run for their money. At one point, his face creases with radiant joy when Norman tells him that a full house awaits his performance; at another, he looks relieved when Norman tells him he will never be forgotten. At yet another, his Scottish burr comes through. Likewise, Shearsmith’s dresser is a wonderful creation: part nagging nanny, part therapist and part colleague, he constantly suggests that there is more behind the facade of helpfulness — until the tragic last scene confirms this. In fact, the final 15 minutes of the play are some of the most well-acted and emotionally thrilling in the West End today.

Foley marshals these performances, bringing out the play’s humour and adding numerous moments when a subtle exchange of looks speaks volumes. On Michael Taylor’s attractively squalid and detailed revolving set, the supporting cast features Harriet Thorpe (Her Ladyship), Selina Cadell (Madge) and Phoebe Sparrow (Irene). While the in-jokes inevitable in a play about the theatre are often amusing, the main problem is that Harwood’s drama is frankly nostalgic, and must have been so even when it was first staged. Its portrait of England as a place of loveable eccentrics who bravely stand up to the Germans, who carry on even when there’s an air raid, and who are good at heart despite their failings, is both self-regarding and out of place in an era of increased xenophobia. Yet while the mystery of why Sir is breaking down is a great big hole at the centre of things, there is still a lot of pleasure to be had from seeing this version of the master and servant relationship, especially when it is so well acted by the principals.

This review first appeared on The Arts Desk