The Entertainer, Garrick Theatre

Tuesday 30th August 2016

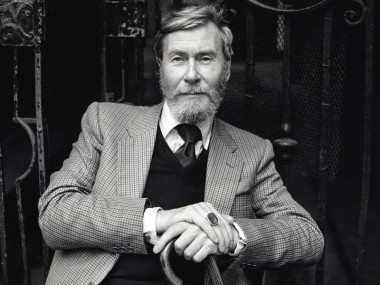

For the final show in his year-long stay at this West End address, Kenneth Branagh has chosen to revive and star in John Osborne’s 1957 play. By doing so, he finds himself once again treading in the footsteps of Sir Laurence Olivier, who originally created the role. It’s not the first time he’s shadowed the legendary actor. In 1989, he played Henry V on film, and then also the great man himself (in the 2011 film Marilyn and Me). But can Branagh make this Angry Young Man period piece, which is both an attack on the British government’s handling of the Suez Crisis and a love letter to the music hall, relevant to audiences in this new millennium?

Set in 1956, the play examines the life of Archie Rice, a failing music hall star. Living in a Northern seaside boarding house with his immediate family — which consists of his second wife Phoebe, his pacifist son Frank and his father Billy, a retired music hall performer — Archie works every night, hammering out his tired and uninspiring routine of patter songs and unfunny jokes. When his left-leaning daughter Jean — who is Phoebe’s step-child and lives in London — makes a rare visit, Archie finds out that her engagement has been broken off and that his other son, Mick, who is in Egypt as part of Prime Minister Anthony Eden’s illegal invasion to hold onto the Suez Canal, has been taken prisoner. By contrast, Frank refused to be conscripted and has spent six months in prison.

Already, and despite the fact that its author was still young, still angry and still oppositional (he used to go on Ban the Bomb marches), this is a play whose politics are not as radical as they could be. For although Jean denounces the prime minister, no one really lays into the whole Suez misadventure, and in the end even Jean seems to accept that marches and rallies won’t change anything. In fact, the overall political tone is one of disillusionment: Frank embraces the idea of emigration to Canada because there’s no “good reason for staying in this cosy little corner of England”, where “you’re nobody.” And his message to Jean is: “You are not going to change anybody.” It’s clear to me that the playwright, already in 1957, with his overt sympathy for the prejudices of Billy and Archie, was well on his way to becoming a reactionary old man.

Osborne intersperses scenes set in these squalid digs with extracts from Archie’s one-man shows. His songs, with titles such as “Why Should I Care?” and “Thank God I’m Normal”, suggest the performer’s desperate need for a mask of insouciance, while deep inside his heart is breaking. Branagh plays him with enormous confidence, emerging from a blaze of light at the back of the stage and tap dancing his way around the shadows. But although he effectively shows Archie’s manic need to keep talking and to keep performing, he isn’t really sleazy enough, nor — as the text demands — “dead behind the eyes”. Branagh simply doesn’t ooze failure.

At his best, this Archie is a cheerful fake, more convincing in his quieter reflective moments than while playing his music-hall routines. The deeper feelings are there all right, but what’s missing is an extra demonic streak, the energy of knowing defeat. And the problem with Branagh’s vaudeville performances is that while Osborne meant them to be second-rate, his are slick, professional and rather good. Likewise, the chorus girls are neither tacky nor nude. Instead they are rather glamorous: more Saturday Night at the London Palladium than end-of-pier Sunday afternoon. By contrast, Greta Scacchi’s Phoebe is pitch-perfect, a working-class woman both protesting against her humiliations and desperate for affection. Likewise, Gawn Granger’s proud and humorous Billy is a convincing version of a 1950s Nigel Farage.

Of the younger actors, Downton Abbey’s Sophie McShera, who plays the oppositional Jean, is disappointing, lacking seriousness and depth, with a voice that is too shrill and unmodulated. On the other hand, Jonah Hauer-King’s Frank is the one actor that really moved me, with his well-judged callow anger and naive sincerity. In general, Rob Ashford’s production, attractively designed by Christopher Oram, is well paced and smooth-running. So despite the contemporary resonances of this old-fashioned play — war, the military and patriotism, Polish migrants and our insular prejudices, the NHS and tax evasion, Labour Party hypocrisy and political protest rallies — this production is Osborne-lite. It’s anodyne, stylish but not passionate, enjoyable but rarely moving.

This review first appeared on The Arts Desk