The Fifth Column, Southwark Playhouse

Wednesday 30th March 2016

Ernest Hemingway was one of the most influential writers of the 20th century. But although his 1940 novel, For Whom the Bell Tolls, is familiar as a classic account of the Spanish Civil War, his 1937 play — which is set in Madrid at the height of the conflict — is, to put it mildly, less well known. Based on real people and real events, The Fifth Column is now revived for the first time in London, but is this story of espionage and betrayal, which is Hemingway’s sole excursion into the territory of playwriting, anything more than a curiosity?

At first things look promising. Set in two adjoining rooms in the Hotel Florida, Plaza Callao, in 1937, the play focuses on Philip, an American who pretends to be a drunk and wastrel, but is in fact an undercover counter-espionage agent on the side of the left-wing Republicans. As he moves into the room next to that of compatriot war correspondent Dorothy Bridges, kicking out her boyfriend Robert, he finds himself torn between her offer to be his fun-loving, and rich, wife, and the greater demands of the political cause. Philip calls Bridges a “bored Vassar bitch” while she insists that he’s just a “Madrid playboy”.

Philip bares more of his soul, such as it is, to Max, a German left-wing activist and Anita, a North African woman who hangs out at Bar Chicote, and who, poor thing, is attracted to him. A handful of other plotlines involve a large cast of bit parts — the hotel manager, an electrician, Petra (Bridges’s maid) and a hotel maid — who are all hungry in what is a siege situation, with General Franco’s fascist forces shelling the city. Yet more bit parts belong to various Republican soldiers, the head of the Republic’s counter-espionage in Madrid, as well as waiters and guitarists, and a group of fascists, which includes a German Nazi general and his entourage. My, it sure gets crowded on the cast list.

The main problem with the play is that Hemingway is a novelist and not a playwright. The scenes set in the claustrophobic confines of the hotel, where there is a lot of potential for dramatic involvement and twisted relationships, have a lot of potential, but when the story starts to roam to other locations a lot of the drama is diffused. And while Hemingway clearly enjoys himself in painting the character of Philip, for all his rambling introspection, his view of the women is superficial and frankly sexist. Anita is described in the programme as “a Moorish tart”, and Bridges is quite banal in her aspirations, and rather an airhead. The unclear plotting, which reveals the existence of the Fifth Column of fascist subversives late in the day, is unfocused, and in general the writing has an inertness which kills any interest that remains. This play probably reads well, but it limps across the stage.

Nor is the politics of the piece of much interest. Hemingway is so fixated on the image of individual male heroism, in which a single great man does great things for a great cause, that he neglects the bigger picture. Unlike George Orwell, who criticised the fatal in-fighting between all of the different lefty groups, Hemingway just fetishises the solitary male. And as for the sexual politics, perhaps the less said the better. Philip’s declarations of love for Bridges at night, and his coldness to her during the day, might sound good on the page, but spoken out loud they are completely unconvincing. In this story, whenever a character speaks of love you instantly disbelieve them.

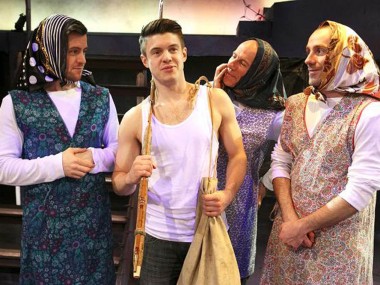

Produced by Two’s Company, which specialises in rediscovering rarely performed work from the first half of the 20th century (a risky strategy at the best of times), The Fifth Column is directed by Tricia Thorns and designed by Alex Marker. Strangely, this gritty 1930s story has no cigarette smoking, although some of the music is recognisably evocative. The cast is adequate, if not inspiring. As Philip, Simon Darwen is perhaps too nice a man to discover the true brute inside his character, although Alix Dunmore and Sasha Frost are very lively as Bridges and Anita, while Michael Edwards makes a good Max and Stephen Ventura a comic hotel manager. But despite their best efforts, in the end this is a charmless, humourless and rather dull evening. Not even much of a curiosity.

This review first appeared on The Arts Desk