The Hills of California, Harold Pinter Theatre

Thursday 8th February 2024

In West End theatre, the cliché that nothing succeeds like success keeps the wheels of commerce turning merrily. But just because a show is selling lots of tickets, and has generated loads of hyperbole, doesn’t necessarily mean it’s any good. The latest case of this is surely Jez Butterworth’s The Hills of California, which has opened in the West End under the direction of Sam Mendes and starring Laura Donnelly (the playwright’s partner), the same winning team that brought us The Ferryman in 2017. This time, Butterworth looks at female family conflicts in Lancashire over two time periods: 1976 and some twenty years earlier.

The plot begins during the summer drought of 1976, and the sweltering set is the public parlour of the Sea View guesthouse, whose name — like much else in the play — has a imprecise relationship to truth: situated in the back streets on the outskirts of Blackpool it offers not a single glimpse of the Irish Sea. As Veronica Webb, the widowed (maybe) matriarch of the family, lies dying of cancer upstairs, three of her four daughters assemble below. Naturally they are well characterized: Jill, who has never left home, is made in the image of a stereotypical librarian (you know, glasses, puritanical, virginal, a bit sad). Her sisters are Ruby, attractive but excitable, and Gloria, capable but angry.

The fourth sister, the eldest, the one who left home many years ago, is Joan. She now lives in California, and Jill insists that she will return to say goodbye to their terminally sick mother. Although Gloria and Ruby point out that she has completely ignored their family for decades, Jill is adamant and this prepares us for the play’s finale. Meanwhile, in scene two, the set rotates and we are in the Webbs’ private parlour in 1958, watching Veronica — who is single and has different accounts of the death of her husband in the war — rehearsing her four girls in song and dance routines based on the songs of the Andrews Sisters. Her ambition is to perform first locally and then at the London Palladium.

Although this is basically a story about a determined mother, a rebellious older daughter and her three siblings, Butterworth fills it with extras: Ruby and Gloria arrive with their husbands, plus Gloria’s children; there’s a visiting nurse, a piano tuner, a local comedian, an American talent spotter, and a doctor. All this creates the illusion of an epic story, although none of these additional characters have much depth and they mainly serve to extend the storytelling to three hours of stage time. Although the early scenes, with their flashbacks from the 1970s to the 1950s, have a tight thematic coherence, and the mixture of one-liners and old-style close-harmony singing is often joyous, the final act is much looser and much less satisfying. Despite the build up, the revelations that arrive feel shallow, unfocused and preposterous.

Thematically, the central preoccupation is Veronica’s desire to make her children — the Webb Sisters — into a successful stage act, an escape from drudgery and a ticket to happiness. Her love of American pop culture, especially the music of Johnny Mercer — referenced in the play’s title — is beautifully captured. The faded glamour of the guesthouse, with its broken jukebox and rooms named after American states, is evoked with charm and humour. At the same time, the theme of disappointed hopes is strongly articulated when, perhaps unconvincingly, its emerges that this family has never heard of Elvis Presley or the advent of rock ’n’ roll. It’s typical of this insular mentality that the husbands in one of the 1976 scenes to complain that pop music has gone down hill since “Rock Around the Clock” and “Eleanor Rigby”.

So The Hills of California has a warm appreciation of the way that a cultural backwater can indulge a love for old-fashioned music, while at the same time it includes a sharp criticism of the lure of fame, and it portrays the experience of one family’s sad illusions. At the heart of the plotting is the way that the sisters, and their mother, all remember what happened when an American agent, whose clients include Perry Como and Nat King Cole (although he might also be an unreliable narrator), came to see the Webbs. It’s hard to discuss this scene without including spoilers, but the fact that he’s attracted by 15-year-old Joan will surprise no one who follows contemporary new writing.

Butterworth’s writing emphasizes illusions, fantasies and competing memories so we get three different perspectives — each influenced by the character of the speaker — on what happened in 1958. Although the playwright certainly supports the #MeToo movement his depiction of the story’s most troubling incident never gives full voice to the victim, and the final speech about it is blatant slut shaming — I know we are meant to question the veracity of the speaker, but still. Butterworth also suggests that Veronica’s painful death is a payback for her neglect of her children. This is all a bit distasteful, but it does offer a sharp contrast with the aspirations and fantasies of the family. The warm glow of some of the earlier scenes darkens as we learn more about the Webbs’ central trauma.

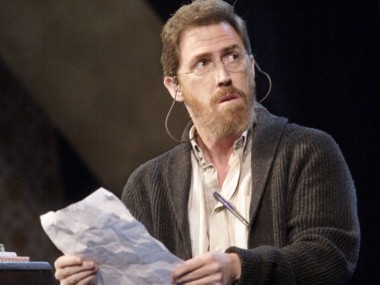

But the lack of dramatic resolution makes it hard to praise a play which, despite a lot of good humour and nostalgic moments, really does need some rewriting. I’m pretty sure it will be a great success, but that doesn’t make it a great play. That said, Mendes — with his designer Rob Howell — does a good job of creating atmospheric stage pictures, while music and movement are expertly put together by Nick Powell, Candida Caldicot and Ellen Kane. The evening boasts a wonderful performance by Donnelly as Veronica, whose luminous quality gives the 1950s scenes a nostalgic appeal, while she is ably supported by Helena Wilson (Jill), Ophelia Lovibond (Ruby) and Leanne Best (Gloria). As the children, Lara McDonnell (Joan), Nicola Turner (Jill), Nancy Allsop (Gloria), and Sophia Ally (Ruby) are excellent, and Corey Johnson’s American agent is suitably reptilian. Butterworth says in interviews that going to theatre nowadays is boring: I can’t think of a better description of the last act of his own play.

This review first appeared on The Theatre Times