The Human Voice, Harold Pinter Theatre

Tuesday 22nd March 2022

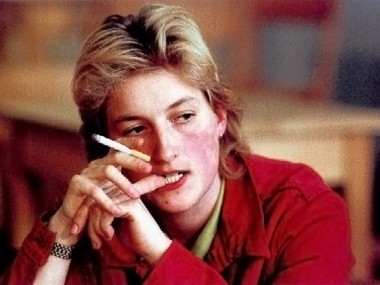

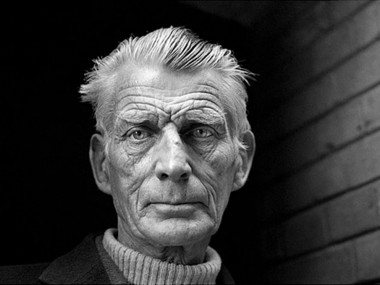

Is there really such a thing as an unmissable show? Depends on your taste of course, but for sheer hype this event takes some beating: two-time Olivier Award-winning star Ruth Wilson (last seen doing her sinister stuff in the BBC’s His Dark Materials) has teamed up with boundary-smashing director Ivo van Hove (whose A View from the Bridge was a decade highlight) to stage Jean Cocteau’s 1930 modernist monologue about a woman waiting for her lover to phone. Part of the hype is the hot cakes effect — the show is in the West End for only 31 performances.

Wilson plays the unnamed woman, a role which both Rosamund Pike and Tilda Swinton have performed on celluloid, and follows Leanne Best at the Gate Theatre in 2018 in a version directed by Daniel Raggett, who has been van Hove’s assistant director. He isolated her in a sealed room in the middle of the theatre, and so the audience eavesdropped on her mobile phone conversation by means of headphones. This time, Wilson is similarly confined in an oblong box, with a large picture window separating her from the audience. A kind of Rear Window for one, a glimpse into a cold morgue perhaps.

As the woman picks up the telephone to take her lover’s call, she has to endure the old-world technology of the land line — with its crossed wires and random connections to other people’s conversations (a rare moment of humour). Once she can speak to him undisturbed we realise that he is leaving her. He would like to have his letters back, and will send his servant Joseph to pick them up. For her part, she wants him also to take her dog, who preferred him and who she has been neglecting. At first she acts casual and lies about how she is feeling. But this doesn’t last.

The woman tries to be brave, but her mask of courage is slipping: she is sleepless, sliding into depression and suicidal thoughts. Gradually, her self-deprecation and ingratiating laugh turn into agitated admissions of emotional distress and the fear of the void. She says that she is not used to sleeping alone anymore and the intensity of her love is expressed by her desire to hold onto a pair of shoes that her lover has left in the flat, objects that smell of him and that she caresses with acute longing. She also wears some of his clothes; she is restless and imagines, in this version, conversations that she has not yet had with him. In van Hove’s adaptation it is a thoroughly contemporary and naturalistic account of the agony of being dumped — with a strong subjective viewpoint.

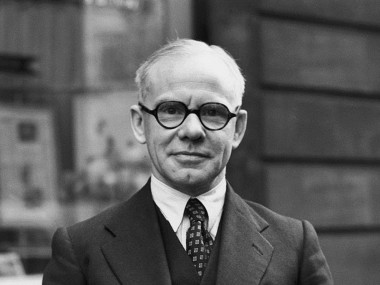

Cocteau was an avant-garde visionary artist, whose writing mixes surrealism with poetic imaginings, but this play is not in the least fantastical. But it does have a European humanist sensibility. Anyone who has ever split up unwillingly with a lover will recognize the scorching intensity of the feelings and the obsessive repetitiveness of the thoughts. Although you could argue that Cocteau’s account of woman as victim, a person who crumbles hysterically when her man leaves her, is an old masculinist fantasy, this play would work equally well with a man in the same role. The story is about how defensive layers are peeled off to reveal emotional truth so in the end gender matters little.

The playwright also explores the, in 1930, relatively new technology of the domestic telephone, a reminder of the intimacy of this instrument — the human voice in your ear is so near, even when the speaker is far away. As if to prove the point, the woman takes the phone to her bed, waiting and waiting for it to ring. Because she feels so thoroughly alone, the machine is a life line — she compares it to the oxygen supply of a deep sea diver. Like a mobile or zoom, it is also a technology that sometimes lets us down, as when she gets a crossed line. But the phone’s aura of intimacy, offering connection in a world of loneliness is the piece’s strongest idea.

Van Hove’s production is, as you would expect, perfect in tone and texture. Designed by Jan Versweyveld, it starts with a blank empty room as Wilson begins grappling with the phone off-stage, and the moment of whiteness is held long enough for it to make us uneasy. As she convincingly plays her character’s role of courageous indifference, the colour palette is beige and the lighting only heats up when her emotions begin to rise. When she opens the window of her flat, the street sounds come flooding in; when she messes up her floor she cleans it with kitchen roll; a musical mash-up signals mental confusion; Radiohead’s “How To Disappear Completely” gets an airing; loud echoes demonstrate the production’s subjectivity.

There is something very European about this production, which almost guarantees that it won’t be very popular in Brexit Britain. There are no easy jokes, and the moments of humour are quickly followed by a contrasting emotion that makes your laughter stick in the throat. There no references to British sitc0ms, or current affairs, or anything so familiar that you can smoothly relax into the performance. No, it’s the opposite; it’s an old play with old sensibilities — and van Hove has deliberately chosen not to make it sweetly palatable. And this is exactly right: the story is of a woman’s disintegration. That must surely be disturbing, and troubling. It can’t be an easy watch.

Wilson plays her part to perfection, a masterclass in control and variation. At every moment, you know what she is thinking and feeling, from calm self-deception to wild hysteria. The passage when she acts out her fear of the neglected dog is stunning, as is the sense of her psychological disintegration under pressure. Every gesture tells its own story. This is not only about the human voice, but also about the human body in all of its sufering and pain. And Wilson gives an utterly covincing reading of a person’s journey from brave face to sheer despair. Yes, this overwhelmingly moving performance is a great 70 minutes of theatre — believe the hype.

This review first appeared on The Arts Desk