The Invention of Love, Hampstead Theatre

Monday 16th December 2024

Can men really love each other — without the sex? Or, to put it another way, how many different forms of male love can you name? These questions loiter around the edges of Tom Stoppard’s dense history play, which jumps from 1936 to the High Victorian age of the 1870s and 1880s, and is now revived by the Hampstead Theatre starring Simon Russell Beale. First staged in 1997 at the National Theatre, The Invention of Love tells the story of AE Housman (Beale), the Victorian classical scholar and poet who wrote A Shropshire Lad, that collection of yearning lyricism. This revival, however, raises questions not only about the emotions of love, but also about the wisdom of respecting a playwright’s wishes. For this three-hour-long version, Stoppard has restored many lines that were cut from the first production — and the result is fuller, but also stodgier.

In typically Stoppardian fashion, Housman’s life is told in a quirky, indirect way. Starting with his death in 1936, we see him meeting Charon, the ferryman who takes him across the Styx. It’s a very funny encounter which soon segues into the Oxford of the scholar’s youth, where the dead AEH meets his younger self. Oxford’s pre-first-world-war golden age is conjured up by introducing historical figures such as Oscar Wilde, Walter Pater, John Ruskin and Benjamin Jowett (hilarious). Later we get to meet WT Stead, the campaigning editor, illiberal Liberal MP Henry Labouchere, and writer Frank Harris.

But the play’s emotional fuel is the unrequited love of the young Housman for Moses Jackson, an athlete as well as a scholar. At a time when “the love that dare not speak its name” was both being medicalized as an inversion, or perversion, and given the name of “homosexuality”, the strong feelings between men were being denounced as “beastly”, and the law against gay sex was being strengthened. So while the queerness of Oxford as a mainly all-male institution can be seen in the spectrum of emotions experienced by some graduates, from bonds of affection to physical sex, the social context was changing rapidly. Suddenly, as in the case of Wilde, the law stopped turning a blind eye and instead embarked on witch-hunts.

So Housman’s strong feelings of love for Jackson, who was straight, result not only in a beautifully awkward scene in Stoppard’s play, but clearly dominated the poet scholar’s whole life. Whatever part of the sexual spectrum he lived on, and we cannot with any certainty know this, Housman certainly experienced intense love for another man, and carried this pain with him for decades. From ideas about Greek Love and mentions of Sappho, the drama shows how such emotions have a history of their own. Although this depth of feeling is at the centre of Stoppard’s play, much of the action tends to obscure it.

The playwright’s text is thrillingly, and often frustratingly, complex. The Oxonians, both professors and undergraduates, discuss classical literature, quoting ancient Greek and Latin, and seem to assume that everyone can keep up with the allusions to Catullus and Lesbia, Aeschylus and Plato, and to lesser-known authors. The effect is that Stoppard pulls you in with his wit and clarity, you feel you understand all for a moment, you see the light exploding in a verbal firework, and then the dark of ignorance descends again. It is an experience which is both exciting in its intellectual stimulation and draining in its demands on our attention. It really helps to have a playtext.

Despite the density, the hugely long passages of discussion and description, and the complexity of some of the examples, many of the play’s points are extremely suggestive: first, the idea that love poetry is not an innate thing, but had to be invented and reinvented throughout history; second, the fact that ancient texts, both classical and biblical, come down to us in imperfect copies of copies of copies (which need to be edited by scholars whose work is as near to science as the humanities ever get); the sense that feelings of love are fluid and fugitive — we all live on a spectrum of emotions.

The sheer Englishness of Stoppard’s wit, with Charon cracking jokes like a London cabbie, and the mixture of cynicism and idealism that characterized the thinkers of “that sweet city with her dreaming spires” comes across as a love letter to England, with jokes about education, sport and art ringing in the air. The world of aesthetes and modern scholarship, of misanthropy and elitism, is brilliantly represented. But, content warning, this is a play about blokes, and many old blokes — if you’d like to see women on stage this is not the play for you.

Housman’s attitudes to other scholars, and to women students, were unkind to say the least, and some of the most hilarious passages involve the guilty pleasures we might feel on hearing his acidic putdowns. The quotations of his poems are typically rapt, and some images stick in the mind. Love, for example, is compared to a piece of ice being held in a fist, a thing that burns but then melts, that is hot but also cold. At his best, Stoppard delivers these shafts of light; but for a lot of the time, as the dons dispute over croquet and the worthies discuss public morals over billiards, the text is simply too rich and detailed to make for easy viewing.

The Invention of Love is one example of a play in which the playwright has fallen so much in love with their subject that they can’t let it go (just as Housman couldn’t let go of his unrequited passion for Jackson). But although much of the research stifles the drama, one thematic aspect of the play does stand out. It’s also about love. The love of knowledge for its own sake. As AEH and his younger self debate the relative merits of being a scholar or a poet, it is the first that becomes his chosen path, the route of textual criticism of the classics. The paradox, of course, is that he is now remembered more for being a poet.

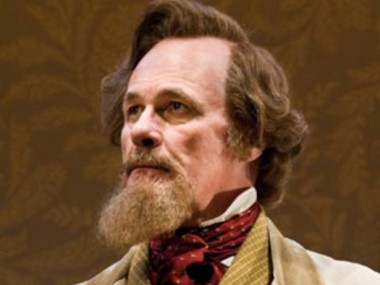

The richness and difficulty of Stoppard’s text is not helped by the production, directed by Blanche McIntyre, which is not without its awkward moments. Morgan Large’s set juts out into the auditorium, but the boats used by the actors are clumsily realized and the stage picture is often ugly. More than once it is hard to hear the dialogue, when the actors aren’t facing the audience, and some of the lighting leaves too many shadows. However, Simon Russell Beale as the dead Housman makes up for a lot of this messy staging: his voice is so distinctly beautiful, so mellifluous, you can listen to it for hours. It’s a small masterclass.

The rest of the large cast feature some good performances: the best by far is Matthew Tennyson as the young Housman, naïve, nervy and a little lost in the world. By contrast, Ben Lloyd-Hughes’s Jackson is hale, hearty and generous-spirited. Dickie Beau’s exiled Oscar Wilde is suitably serene, with a touch of acid, while Stephen Boxer’s Jowett is energetically funny. Alan Williams’s gravelly Charon is one of the show’s highpoints. This is an evening which has many joys and pleasures, although its masculine verbosity will not be to everyone’s taste.

This review first appeared on The Arts Desk