The Kitchen, National Theatre

Wednesday 7th September 2011

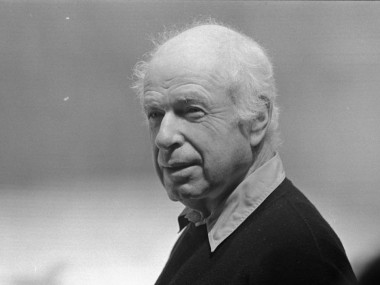

Twenty years ago, when I first started reviewing, playwright and one-time Angry Young Man Arnold Wesker was one of British theatre’s duds, more admired abroad than at home. Although he featured in all the history books, most of his work was ignored. Stephen Daldry’s revival of his 1959 play, The Kitchen, in 1994 was a rare moment of appreciation. Apart from that, Wesker was rumoured to have retired in embittered isolation to a Welsh farmhouse.

This year, however belatedly, Wesker is making a comeback. In June, there was an excellent revival of his Chicken Soup with Barley, the first of the Wesker Trilogy, at the Royal Court. Now, the National Theatre (no less) offers a big-stage, high-profile version of The Kitchen. Set in the busy, overheated kitchen of the Tivoli restaurant, the play gives glimpses into the lives of several of its toilers, but its real subject is work itself.

First a porter arrives, lights the ovens and prepares for the various cooks, who gradually turn up, as do the waitresses. Preparations start slowly, but as the customers arrive for lunch, the pace of work increases, growing into a diabolical frenzy during which a thousand meals are served. After the interval, there’s an afternoon lull, during which the staff take a long break, followed by a less intensive evening routine.

As in any workplace, you soon get to know the workers, who are a mix of Brits and immigrants. There’s Peter, an intense and energetically playful German fish cook who’s in love with Monique, a married waitress; Paul, a Jewish pastry chef; Dimitri, the Greek porter; Max, the beer-drinking butcher; Bertha, the large vegetable cook; Kevin, an Irish newcomer. Towering above them, sometimes literally, is Marango, the money-obsessed owner of the Tivoli.

Giles Cadle’s heroically clean steel and wooden set is huge and looks like a display of engineering enveloped in a massive blackboard on which the names of the dishes are highlighted. As the rhythm of work gradually accelerates, the ovens hum, the pans begin to bubble and crash, while the cooks and chefs chop, cut, beat, roast and fry the hundreds of orders shouted out by the stream of waitresses. Steam rises, smoke belches. There’s an industrial accident.

During the afternoon break, the lovesick Peter — who has had a jealous fight with one of his fellow workers — tries to see beyond the daily grind. He imaginatively builds an arch out of kitchen equipment, and challenges the other staff members to articulate their dreams. Although he rejects these as banal, he is unable to offer a dream of his own. This leads inevitably to his climatic rebellion: an act of pointless nihilism.

Hard work by a superb 30-strong cast, led by Tom Brooke as Peter, sums up our national identity: the play offers a picture of a multicultural society where the rich hold the power, the managers are disgruntled and fairness has been banished into the cold. If you are what you eat, the Brits are here portrayed as the victims of sour soup, unidentifiable fish and indescribable meat, although they also have a sweet tooth.

While Wesker has cleverly orchestrated the work flow of this busy kitchen, and entwined numerous small stories into the insistent necessities of the service industry, his main aim is to convey the sheer drudgery and dehumanising effect of relentless and underpaid work. Ignoring this, Bijan Sheibani’s beautifully choreographed version creates a balletic entertainment which is visually impressive but politically ineffective. He uses a series of theatrical devices — dance moves, freeze frame, synchronised miming, glowing lamps, bursts of flame, a flying waitress — to serve up a brilliant entertainment. But amid all this visual fun, the politics of the piece get muted. It no longer seems like hell to work in this kitchen: it actually looks like fun. Why rebel against exploitative work when everything is so enjoyable?

© Aleks Sierz