The Knowledge, Charing Cross Theatre

Monday 11th September 2017

The black cab is such an iconic symbol of London that it’s easy to forget that inside every taxi there’s a human being who has spent a lot of sweat and tears learning the Knowledge, which is the location of thousands of streets and landmarks within a six-mile radius of Charing Cross. Anyone who wants to drive a London cab must memorise them all. Jack Rosenthal’s The Knowledge is a classic 1979 ITV film about how a group of aspiring cabbies learn the runs, or routes, that enable them to pass the frequent tests they have to sit before they are given their green badge, or licence to drive a black cab.

Now neatly dramatized for the stage by Simon Block, the play features three distinctive couples: youngsters Chris and Janet (unambitious man pushed by ambitious woman); Gordon and Brenda (faithless husband more interested in sex than in working); and the older Jewish pair, Ted and Val (his photographic memory is a real asset). Along with Miss Stavely, the only female candidate, they have to learn the Knowledge, which involves some 468 runs of 34 streets each: total 15,000 streets. This takes at least a couple of years, and the failure rate is 70 per cent.

As Mr Burgess, their teacher, explains, licensed cabbies started with Oliver Cromwell in 1644, and they have been going ever since. His examination techniques are so rigorous that he has been nicknamed “The Vampire”, and you can see why. Every few weeks, the hopefuls attend a personal interview with him in which he asks them to recite some of the runs they have learnt, while doing anything he can to put them off. They must stay cool despite the provocation — a good training for the work. They must stay focused on the task in hand. It’s a powerful reminder of the skills needed to qualify as a cabbie. These are not mere “driving jobs” — it’s an extremely demanding apprenticeship.

Of course, Rosenthal evokes a world before the proliferation of mini-cabs and the arrival of Uber, so there’s a mildly nostalgic tinge to this story, but Block’s version conveys both the humour and sadness of the original. The pressure of learning the Knowledge is so great that each of the couples comes under almost intolerable strain. With a mixture of empathy and psychological realism, Rosenthal shows how every man needs the help and support of a woman. Each of the couples functions as a unit. Yet he also stresses how the obsessive commitment needed to acquire the Knowledge (the men talk of little else, even begin to dream of street runs) results in break-ups and personal tragedies.

So the politics of the piece are not just about the enormous skills required to be a black cab driver, but also about the personal costs of ambition. If, as all the characters realise, becoming a cabbie is a good job for life, highly skilled and well paid, the costs of independence include both loneliness and a strain on family life. Although Rosenthal doesn’t dwell on the clichéd image of the big-mouthed Tory cabbie, presenting instead a much more sympathetic view of working-class life, you can see how the conditions of work, and the pride of learning the Knowledge, might contribute to a singular sense of individualism and belief in free-market ideology. For the play’s characters, however, all that lies in the future.

If the couples are neatly distinguished individuals, much of the fun of the show comes from the figure of Burgess. A classic English eccentric, he tongue lashes the candidates, giving reality checks and often behaving like a petty tyrant. (Give a grey man some power and watch him abuse it.) Yet he also has his moments of humanity, a caring side that occasionally is allowed to peek out. Likewise, the lone figure of Miss Stavely is given the role of making feminist points that, however clumsily, reminds us that this all-male world of cab drivers has been gradually changing for decades.

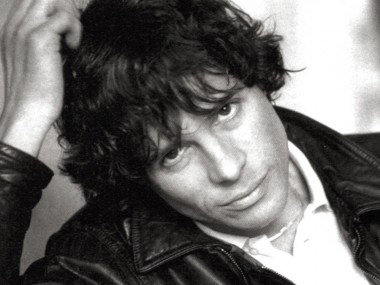

Directed by national treasure Maureen Lipman, Rosenthal’s widow since his death in 2004 and who played Brenda in the original film, this is a smooth and fast-moving story which uses the stage space well enough. If it doesn’t have the freedom to flow as well as the film version, perhaps a more experienced director would have removed some of designer Nicolai Hart-Hansen’s stage clutter, but in general Lipman delivers an entertaining evening. Steven Pacey positively exults in Burgess’s odd mannerisms, even taking his curtain call with a toothbrush (used to comb his tache and eyebrows), while Ben Caplan’s Ted is a moving portrayal of the highs and lows of middle-aged retraining. As the young couple, Fabian Frankel and Alice Felgate are often convincingly callow, both growing during the evening, and James Alexandrou and Celine Abrahams give Gordon and Brenda the required depth. Louise Callaghan’s Miss Stavely delivers her points with the necessary assertiveness. This is an informative and fun version of a memorable film.

© Aleks Sierz