The Libertine, Haymarket Theatre

Tuesday 27th September 2016

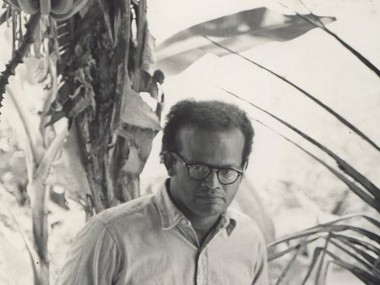

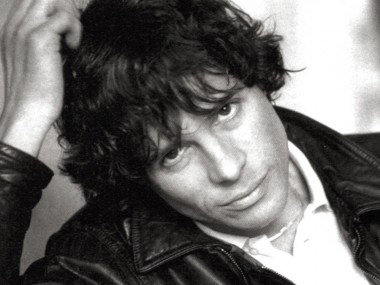

Restoration theatre has the reputation of being a rake’s paradise — all those randy young aristos in hot pursuit of buxom wenches. But even in the depths of 17th-century playwriting, there was room for repentance and regret among the discarded petticoats and ripped bodices. So it is with Stephen Jeffreys’s The Libertine, his now sharply rewritten 1994 play that was also made into a film starring Johnny Depp. In this revival, the central role of John Wilmot, Earl of Rochester — the archetypal rake — is taken by Dominic Cooper, whose most famous theatre and film outing was in The History Boys.

Right at the start, Cooper’s Rochester swaggers confidently onto the stage, secure in the knowledge of his own powers of attraction — remember him as the young hunk in Mamma Mia!? — and directly addresses the audience: “Do not warm to me,” he says in the play’s prologue. Why? The reason is clear: he’s dangerous — he not only breaks hearts, he crushes the pieces underfoot. Powered by a rage against life itself, his natural powers of intellect and sensibility are directed towards criticism of king and country, and his stinging satire at the aristocrats of Charles II’s court. Starting in 1675, Jeffreys’s marvellous biographical drama charts Rochester’s slow decline from royal favourite to shambling wreck.

But, for a while at least, things look rosy. Although his indiscretions have previously resulted in banishment from court, Rochester is now back in Charles’s favour. And his intimate life is played out among three women: his highly moral wife Elizabeth, his saucy mistress Jane, and Mrs Barry, a newly arrived but feisty actress. Each represent a different facet of his existence: family, sexual experiment and art. But as he falls in love with Barry, his self-destructive urges push him towards the limits of his physical capabilities. At the same time, Charles commands him to write a play extolling the monarchy. Yet when the king sees the playfully obscene result of this commission all hell breaks loose.

Setting Rochester in the company of his cronies — who include the playwright George Etherege, aristo Charles Sackville, Billy Downs, a bright spark, and the gloriously named servant Alcock (Will Barton) — Jeffreys argues that Charles set the tone of licentiousness in his morally corrupt court, and that Rochester’s obscene verses and astringent satires were aimed at exposing the void at its heart. The playwriting is full of the smells of sex and the odour of disgust; the thrust of the dialogues burns with a lusty vigour and then collapses into the damp sheets of morning-after regret. If occasionally the writing is a touch too explicitly declamatory, the storytelling is confident and compelling.

Of course, the emphasis on sexual physicality has a long history, going back at least to the bard’s “rank sweat of an enseamèd bed, stewed in corruption, honeying and making love”, and Jeffreys has a good ear for catching the lightning wit of Rochester and his clique. Their mocking mimicry of playwrights such as John Dryden is both fun and spot-on. I also liked the picture of Restoration theatre, with his addition of Molly (Lizzie Roper), a humorous stage manager who puts the pretentions of the writers into perspective. Ditto for this version of actor Barry, here taught by Rochester to replace stylised rhetoric with true feeling. But while the hell-raiser employs his talents penning scabrous and scatalogical verses, it is Etherege who writes the classic play, The Man of Mode, inspired by his friend’s behaviour.

Basically, The Libertine, which transfers from the Theatre Royal Bath, is a wonderful play about theatre, about excess and about the despair which stems from the meaninglessness of life. Some scenes — when Rochester has his portrait painted with a monkey or the Signor Dildo chorus — are screamingly funny, and entertainingly critical. The clash between the extreme cynicism of Rochester and the more level-headed women, such as his wife Elizabeth and Barry, is well crafted and intelligent. And the dirty jokes are, as ever, a real delight. There is plenty to love here, even when Rochester’s behaviour is appalling.

Terry Johnson’s bright and energetic production is dominated by Cooper’s charismatic personality, physically robust and increasingly full of dark emptiness. He combines charm and fury in equal measure and effortlessly bestrides the story, both convincing in his theory that humans are animals and aware of his own absurdity. The three main women in the large cast refreshingly give voice to female criticism of male destructiveness: Ophelia Lovibond (Mrs Barry), Alice Bailey Johnson (Elizabeth) and Nina Toussaint-White (Jane). They are thoroughly supported by Jasper Britton (Charles), Mark Hadfield (Etherege), Richard Teverson (Sackville) and Will Merrick (Billy). With an attractive staging designed by Tim Shortall, in a warmly golden theatrical venue, this is a really entertaining West End play that both dazzles and amuses. It’s perfect, it’s profound, and it’s fun too.

This review first appeared on The Arts Desk