The Mentalists, Wyndham’s Theatre

Monday 13th July 2015

Okay, so you’ve got this really great idea, a real vision — one that could actually change the way people live. Ordinary people; people like you and me. You know, solve all the problems of modern life and create a utopia, a new future for society. All you need to do is tell people about it, and then they will flock to join in. But how do you do that? In Richard Bean’s black comedy, which was first staged in 2002 at an experimental studio space in the National Theatre and is now revived in the West End with Stephen Merchant (stand-up comic and co-creator of The Office) making his theatre debut, the answer involves making a video.

The story is set in a tasteless three-star bed-and-breakfast hotel room in Finsbury Park, north London, designed by Richard Kent. This has been booked for £40 for one day only by Ted, an edgy fleet manager from Swindon, who decides to make a video about his big idea for saving the world and setting up an utopia community. He enlists the aid of his old mate, the quiet and reasonable East End barber Morrie, who owns a video camera because he makes porn movies on the side.

As the two men set to work, the nature of Ted’s obsessive becomes clear. Having accidentally found a novel — Walden 2 — by the psychologist BF Skinner, he wants to change society by changing people’s behaviour. Skinner’s method, humorously outlined here, is called behavioural psychology and it does have an appeal. And Ted has all the burning conviction of a fresh convert: “Think about it, if you’re sitting on a bus you don’t give a damn what the bloke next to you is thinking about, do you? It’s what he’s doing with his hands that makes you nervous.” Not content with that, he mocks all those who Skinner called “mentalists” – people who study the way the mind works without taking into account what people actually do. In his evangelism, he is a satirical symbol of all the fanatics who would like to radically change the world.

As Ted warms to his obsession, a picture of Britain as an angry nation emerges. This is a land across which frustrated and embittered men roam around, ranting against litter louts and the education system, attacking Guardian readers and uttering venomous opinions about this, that and the other. Open any copy of the Daily Mail to get a taste. There is something both endearingly cranky, and decidedly sinister, in this portrait of quasi-fascist English eccentricity (which is one of Bean’s great subjects). It also creates a serious undercurrent to a dialogue that fizzes with eyebrow-raising ideas and jokey give and take.

At the same time, while this has been marketed as a hilarious comedy, it really is only fitfully funny. Written early in Bean’s career, there’s a relentless chasing after the punchline in the writing which can be wearying after the first half hour. And there’s more than just a touch of his own stand-up routine. What suffers most from this is the characterisation, and the fact that The Mentalists is actually a rather touching picture of a couple of needy men, whose lifelong friendship has been forged in the shared experience of childhood adversity. Gradually, the manic Ted meets his match in the milder Morrie, whose stories of his sexual exploits and manipulative emotional relationships grow increasingly darker.

Despite their mutual exasperation with each other (both are self-destructive liars and Ted’s promise to give Morrie some cash for his filming is unlikely to be fulfilled) there is more than a touch of tenderness in their relationship, which culminates in a wonderful moment when Morrie asks Ted to choose between three versions of the truth, each represented by an object in the room: a coke bottle stands for real utopianism, a pepper pot for a scam and a fruit bowl for sheer craziness. Likewise, a running joke involving sandwiches provides some good guffaws.

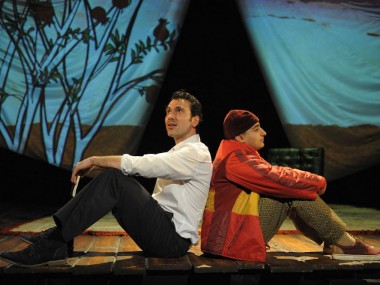

Merchant, who stares with genuinely disturbing glazed eyes from behind the spectacles of his fantasies, looks and acts like a pub prophet as he twists and turns his supple body, contortions which resemble his character’s evasiveness. And the whine in his voice is just right. He is neatly contrasted by Steffan Rhodri, who resists the temptation of making Morrie camp and opts instead for a kind of battered vulnerability and indomitable resilience. Abbey Wright’s efficient production can’t quite overcome the staic quality of the play, and the evening is broken up by an unnecessary interval. Clearly inspired by Pinter’s The Dumb Waiter, Bean has slightly updated this two-hander, which nevertheless still retains the feel of an apprentice work. But, as it becomes clear where Ted’s headbanger ranting, for all its vivid humour, is leading, you slowly realise that the mentalists might have had a point after all.

© Aleks Sierz