The Night of the Iguana, Noël Coward Theatre

Monday 15th July 2019

One of the glories of contemporary London theatre is its revivals of classic American drama. Year after year, audiences are able to revisit and enjoy the great landmarks of postwar American playwriting from greats such as Arthur Miller, Tennessee Williams, Sam Shepard and David Mamet (recently joined by the likes of Lynn Nottage). Now the latest addition to the West End’s current glory days is Williams’s 1961 masterpiece, The Night of the Iguana, in a great production whose starry cast includes Clive Owen, Lia Williams and Breaking Bad’s Anna Gunn.

The story is set in 1940, on the veranda of the Costa Verde hotel on the west coast of Mexico. The second world war feels far away, although a family of German tourists keep criss-crossing the stage, celebrating their victories in the early stages of the Battle of Britain. Similarly distant is the United States of America, despite the fact that several shades of American angst are brought in front of us by the defrocked Reverend T Lawrence Shannon (Owen), who has fetched up in desperation at the run-down hotel managed by his friend, the recently widowed Maxine (Gunn). Shannon is a born hustler: having been locked out of his church by the congregation who think his sermons are blasphemous, he is taking a party of American tourists across Mexico.

On the verge of a nervous breakdown, fueled by both his alcoholism and his antagonism to all formal religion and authority, Shannon takes shelter with Maxine, while his tourists, led by the formidable Mrs Fellowes (Finty Williams), demand to continue to the next town. The full extent of Shannon’s disgraceful blowing of his career chances is indicated by the fact that he has been caught having sex with Charlotte (newcomer Emma Canning), who is barely 17, which means that he has committed statutory rape. The relationship between Shannon and Maxine, the two rebels, gets a further twist with the arrival of the classy but poor artist Hannah (Lia Williams), who is crossing the country with her nonagenarian poet grandfather Nonno.

Appearances are deceptive: like Shannon, Hannah is a hustler. In her case she pays her way, or not, by selling portrait drawings and paintings, while Nonno struggles to finish new poems that can be recited, or sold. In Tennessee Williams’s plays, damage attracts damage, and the three-way relationship between Shannon, Maxine and Hannah is a fascinating portrait of the psychology of outsiders. The playtext fully embraces the best and worst of humanity, and Williams’s sympathy for life’s losers, failures and sinners is evident in every passage. As his main characters discuss the “spooks” of their depression, or ruminate over the symbolism of a tethered iguana, you feel the playwright understands all about the human heart, whether reptilian or not.

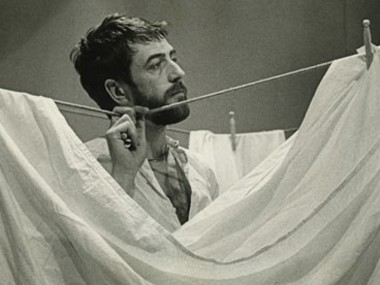

James Macdonald’s superb revival, which boasts a majestic creeper-strewn mountain-top set by Rae Smith, rightly focuses on the central performances: Owen begins the evening as a nervous fidget, pacing the stage, calling out God and sneering at any social or sexual convention that might cross his path, and then some, before nosediving into violent paroxysms of delirium, eventually emerging at the end of the evening with a palpable touch of grace. His seediness is indicated by his left hand being constantly in his trouser pocket, fiddling about. At the climax of the show his anguished fits are positively frightening. It’s an amazing effort.

By contrast, both Gunn and Lia Williams are more grounded, with the former displaying an attractive mix of feisty, almost raunchy, womanhood with notes of vulnerability peeking through; Williams, as the “New England spinster”, convincingly exudes the calmness of the secular saint, as well as the dry humour of a lifelong hustler: but there are beautiful touches too — the moment when she removes Shannon’s cross from his neck is one of exquisite tenderness. Together, all three stars make this a thoroughly moving night, and they are well supported by Canning as the rejected teenager, Finty Williams as the icy matron and Julian Glover as the absent-minded Nonno. The Nazi family is played for laughs, but never caricatured.

Of course, Owen’s portrayal of Shannon, a selfish man who is so self-destructive that he not only abuses alcohol, but also young women, reminds us that this character, for all of the playwright’s sympathy for him, is definitely incorrect politically. Today, it is the women, Maxine the survivor of course, but mainly Hannah the observant and perceptive analyst of human emotions, that draw more audience empathy, and this is palpable in the theatre. Owen can dominate the stage with his entertaining masculine angst, his rants against religion and against conformity, and there are moments when it seems that he genuinely reaches deep within, but it remains a fact that this crisis of masculinity is revealed, by Williams’s memorable Hannah, as self-serving self-dramatization.

Around these core performances, Neil Austin and Max Pappenheim’s lighting and music create both the terror of tropical storms and the almost religious shafts of illumination. The play’s central conflict between individual self-understanding and mindless conformism, as well as the contrast between the fantastic and the realistic, comes across more and more strongly as the three-hour evening progresses. Despite the many laughs and comic passages, this is an essentially serious play for serious people. And it’s an emotionally generous production of a generous-spirited classic. As you leave the theatre you feel like singing: “Free your inner iguana!”

This review first appeared on The Arts Desk