The Poltergeist, Southwark Playhouse

Saturday 21st November 2020

Playwright Philip Ridley has had a very productive lockdown. Despite the constraints of the pandemic he has been exceptionally creative. In March, when all theatres in Britain were closed, his latest, The Beast of Blue Yonder, was scheduled to open at the Southwark Playhouse on 2 April. Since this was impossible, the company came up with an idea called The Beast Will Rise, in which each cast member of the play performed one new monologue each week, streaming from the Tramp Productions website. These number 14 in all, and vary from River (two minutes in length) to Eclipse (almost an hour). What distinguishes them is that they allude to the current virus pandemic without being literal; everything is done through metaphor. And the same imaginative flair can be witnessed in Ridley’s latest show.

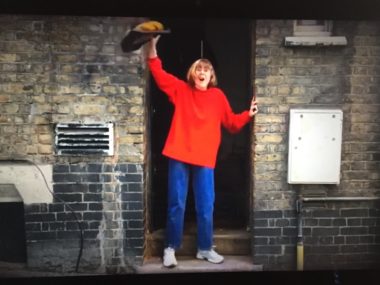

Once again, history repeats itself: The Poltergeist is a new monologue which was due to open at the Southwark Playhouse, but the second national lockdown meant that the show, performed live, is only available as a digital stream. But that doesn’t make it any the less gripping; in fact, the filming adds texture to Joseph Potter’s sublime performance of Ridley’s wonderfully dark and humorous text. The cameras confidently frame Potter, catching him as he strides vigorously over the bare stage, acting out not only his central character’s subjective thoughts, but also the dialogue of all the other people in the story. And, boy, what a story it is.

We begin mundanely in a tiny, once-mouse-infested flat above a dry cleaners in Ilford, East London. This is home to Sasha, a young man who guides us through his story. He lives with Chet, his partner, and he’s not feeling very well. His skull is bursting with a headache, and he’s totally dependent on painkillers. Can he just slink back to bed? No, he cannot. For today is the day of his niece Jamila’s fifth birthday party — and they both have to go. But he’s not looking forward to this “shitty shindig” for this “brat”. And, as the celebrations get underway, Sasha unwillingly interacts with his older brother Flynn and his wife Neve, and we witness not only his commentary on his family, but also get to understand the tragedy of his life. For he has gone down in the world.

At the age of 15, Sasha was a teen prodigy, a young boy who was getting ready to amaze the art world with his painting. But then something went wrong, and he blew his chances. As Flynn and Neve introduce him to various other guests, who include Neve’s parents and Dougie, a plumber who does art as a hobby (a “hobby”!) , polite curiosity becomes intrusive questioning and Sasha feels himself losing control. The party quickly turns into a “new circle of hell” as buried family memories surface and concealed antagonisms come gasping up for air. Amid all the pinky and sickly-sweet decorations and references to The Little Mermaid, only Robyn, Jamila’s sister, can offer a touch of redemption, a slight sliver of hope.

Ridley’s text is superb: typically energetic, with vigorous storytelling and a dazzling mix of heart and head. He clearly shows how families fight over memories, with disputes over what actually happened being carried on for years, and other people (old neighbours and new acquaintances) being sucked into the dispute. His story has a great big splash of ambiguity, as well as being an all-too-recognizable comedy of suburban manners, where clichés make you grit your teeth and where humanity is always held at bay by social expectations. More intimately, Sasha and Chet’s relationship has both a frank eroticism and moments of loving tenderness, along with exasperation and the predictability of the only-too-well-known. In terms of art, the play text also stresses the fragility and imperiousness of the creative spirit.

Despite its moments of cruelty, fueled by the various strains on Sasha’s emotions, and by his memories of his mother, there is also a loving lightness of touch here too. The comedy is superbly articulated, as the monologue spins between Sasha’s amusingly frank inner thoughts and the fast-moving conversations of the party, with an ever-increasing acceleration towards the emotionally true and satisfying climax. Reminiscent of Ridley’s equally brilliant party scene in Radiant Vermin, The Poltergeist is not only a convincing exploration of grief and artistic creativity, as well as of self-awareness and lies, but also uses the metaphorical possibilities of its title to good dramatic effect.

As directed by Wiebke Green, this is not just a tour de force of writing, but also of performance. Potter powers his way through the 75-minute show, at one moment smiling in the warmest way, at the next glowering with ill-concealed hatred. Slightly disheveled, bursting with energy, he takes your breath away with Sasha’s paranoid moments, his insistent critical verve, and his put-on bonhomie. Wow. Highpoints include not only his inevitable breakdown, but also the way he gives life to the beautifully written free-floating space fantasy. Moments of silence or a blush at an unexpected compliment emphasize the writing’s psychological depth and his party piece — a list of art movements since the 1900s — is simply and dynamically brilliant. Thank you Philip Ridley, and theatre company Tramp, for this compelling monologue, which is surely the highpoint of the second lockdown. Phenomenal!

This review first appeared on The Theatre Times