The Prudes, Royal Court

Tuesday 24th April 2018

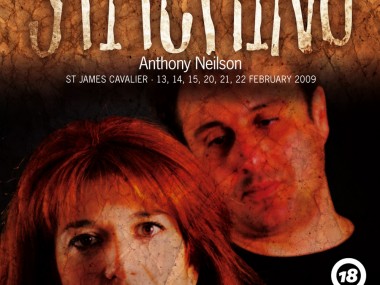

Playwright Anthony Neilson has always been fascinated by sex. I mean, who isn’t? But he has made it a central part of his career. In his bad-boy in-yer-face phase, from the early 1990s to about the mid-2000s, he pioneered a type of theatre that talked explicitly about sex and sexuality. I remember watching his searing and provocative plays, such as Penetrator (1993), The Censor (1997) and Stitching (2002), with my heart in my mouth, and my legs firmly crossed. The content was explicit, emotionally grounded and rarely heard in public. Since then, the playwright has diversified his output, but his new Royal Court two-hander returns to his trademark interest: sex.

This time Neilson’s subject is the taboo on talking about the absence of sex in a relationship. The details read like a therapist’s notes: James and Jes are a professional couple in their late 30s, and have been together for nine years. For the past six years they have been cohabiting. The only problem, and it is a problem, is that they have not had sex for, according to her, 14 months and four days. They have no kids so they can’t claim to be too exhausted to do it; they are too young to be experiencing a mid-life crisis; they have had therapy before, but it hasn’t solved anything — and so it remains a problem. Especially for her: Jes is really fed up. So she’s suggested a daring solution.

Jes has decided that they will have sex again tonight. Because they are not prudes, the conceit is that they will have sex in front of an audience in the lovely warm surroundings of this studio theatre, which has been turned into a cosy boudoir: thick carpet underfoot, fancy drapes and a mattress with two pillows. Atmosphere: nice and pink. Thank you, designer Fly Davis. The emotional coolness between them is neatly conveyed by the distance between the two stools on which they perch as they talk to the audience. Two bottles of white wine are on hand to help them relax. It’s a provocative set up. So, what’s stopping them?

Basically, James is chronically unable to get it up. As the couple talk to us, and to each other, the details of their relationship spill out. Everything has always been fine, until about 14 months ago. So what happened then? James admits that it is his inability to sustain an erection that is the chief symptom of their lack of intimacy, but instead of telling us why that is, he regales us with lots of oddball stories, makes many empty declarations, and regularly collapses into agonies of self-doubt — anything to avoid sexual activity. Jes is no fool, and nor are we. As their therapist has already told them, this behaviour is classic avoidance activity. The man voices his doubts instead of confronting the root of the problem — his desire to dominate, his anger at female independence, his inability to accept change.

All this psycho-sexual material is all presented not as a standard play, but as a 75-minute show. And it is playful. And hilarious. The dialogues and monologues are perceptive and revealing, and the taboo details about masturbation, childhood sexual feelings and even rape are mixed with ridiculous sections about dressing up and theatrical blasts of dry ice and drum rolls. Mentions in passing of Jimmy Savile and Kevin Spacey add to the piece’s provocative edge, but are less interesting than the exploration of James’s fragile masculinity. In the end, however, the lack of a fully dramatized story does mean that both characters come across more as case studies than as fully realized individuals.

There’s also something of a tease in a show that sets up an emotional situation — a couple who get on well with each other, but are now effectively celibate — and then doesn’t reveal the real reason for this. I mean, we get lots of evasive explanations from James, and some strong and stinging retorts from the increasingly angry Jes, but there really is no satisfying resolution to the story. James’s theory that various incidents in Jes’s past life have upset him and made him impotent is quite rightly dismissed both by her, and by us. But, apart from his male ego, no other explanation is forthcoming. Okay, you can argue that this is true to life, and it probably is, but in the theatre it makes for not a little frustration.

Despite that, there’s much to enjoy in this evening of wisdom and fun, directed by Neilson himself, as Jonjo O’Neill (James) and Sophie Russell (Jes) have great onstage empathy and excellent comic timing. They effectively make light of some rather troubling material and the constant interaction with the audience keeps us all on our toes. Occasionally, the lighting (by Chahine Yavroyan) changes, as in the crucial storm-lamp sequence, and the tone darkens. And then lightens during a pillow fight. And then darkens again. Yet in the end there’s something a bit dissatisfying about the slimness of the show, and you do leave the theatre nursing your disappointment with the lack of a climax.

This review first appeared on The Arts Desk

1 Comment

on Friday 27th April 2018 at 6:38 pm