The Royale, The Tabernacle

Tuesday 8th November 2016

With the Bush Theatre’s main building undergoing renovations, this company’s shows are being staged in a selection of temporary spaces in West London. So, on this dark and freezing evening, I make my way to The Tabernacle, a Grade II-listed building in Powis Square, Notting Hill. It was once a church and is now a community centre. In the 1990s, the North Kensington Sports Academy trained young boxers here, so it’s a particularly apt venue for this restaging of American playwright Marco Orange-Is-the-New-Black Ramirez’s 2015 Bush-hit The Royale, a drama about this bloody sport.

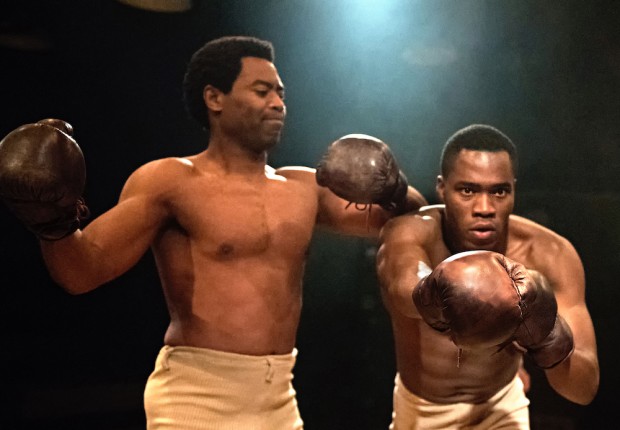

If storm clouds are gathering outside (it’s the night of the American presidential election), inside The Tabernacle the atmosphere is warm and welcoming. With the audience taking their seats on four sides of a makeshift boxing ring, we get ready to witness the fight of the century. Loosely based on the true story of Jack Johnson, the Galveston Giant, Ramirez’s 90-minute drama gives us a ringside view of the black boxer Jay, and his relationships with Wynton, his trainer, and Fish, his sparring partner. Set in the first decade of the 20th century, the piece starts with a bout, recreated in a vivid and symbolic style — in this production both text and performance knock out naturalism right at the start.

Jay’s overwhelming ambition is to fight Bernard “the Champ” Bixby, the white heavyweight champion of the world. But, as his promoter Max points out, such a match has never been fought before. We are, after all, in the era of Jim Crow (racial caste system) and the strict segregation of black people in the South; a time of horrific lynchings, the Ku Klux Klan and racist mob rule. In this context, although the championship fight is successfully set up, it is the arrival of Nina — Jay’s big sister — that really raises the stakes. She reminds her brother of the wider racial implications of his ambition.

Although Jay has not seen Nina for many years, he remembers vividly an incident from his childhood that shows how the oppression of black people is as much cultural as physical, a psychological colonisation where advertising is as effective as bull whips. Ramirez describes all this in a spare but direct style, and with great originality and freshness. If occasionally his depiction of psychology is not entirely convincing, this is compensated for by his freshness and his energy. When the big match finally arrives in a fast-moving show, it is a masterclass in the delivery of tension and excitement. But as well as effective storytelling, Ramirez is also careful to include some haunting and resonant metaphors.

The Royale of the title, for example, is a barbaric boxing event which reminded me a bit of the dance marathons of the 1920s, as depicted in the 1969 film They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?, and illustrates the brutality of this particular sport. In general, this play is a chilling reminder of the appalling nastiness of both boxing and racism, and the blood-red injustice that runs like a scar through American history. In the era of the Black Lives Matter movement, there’s no need to reiterate the relevance of this heritage. As Nina asks, if Jay wins and beats a white man, how strong will the backlash be?

Madani Younis’s powerful production, on designer Jaimie Todd’s bare-plank set, lets these David and Goliath resonances — which include the assassination of black icons and foretell the rise of Muhammad Ali — speak for themselves. His cast is led by Nicholas Pinnock, whose Jay is light on his feet and has an impressive stage presence, whether dazzlingly us with his grin or worrying us with his scowl. Sadly, the unforgiving acoustics of this venue and some indistinct delivery by Jude Akuwudike (Wynton), Martins Imhangbe (Fish) and Patrick Drury (Max) means that the story is hard to follow at times, although Franc Ashman’s fierce Nina is a model of clear diction. The physical force of the actors injects the story with adrenaline. At one point, Younis has Nina strike her brother while he’s in the ring, a moment rich in psychological and metaphorical meaning. All in all, this is a strongly written and strongly staged episode of American history that is horrific rather than inspiring.

This review first appeared on The Arts Desk