The Son, Kiln Theatre

Wednesday 27th February 2019

Well, you have to hand it to French playwright Florian Zeller — he’s certainly cracked the problem of coming up with a name for each of his plays. Basically, choose a common noun and put the definite article in front of it. His latest, The Son, is the last in a trilogy which includes The Father and The Mother. His other recent work is titled The Truth and The Lie — see what I mean? Peasy. Then there’s The Height of the Storm, a slight variation. Anyway, the previous parts of the Moliere-Award-winning writer’s trilogy have won an Olivier (The Father) and critical acclaim (The Mother) so what can we expect from their offspring The Son?

To begin with, the set up is quite familiar: we are in a chic apartment in Paris, complete with elegant chaise lounge, where a middle-aged and middle-class divorced couple, Pierre and Anne, are puzzled by the behaviour of their 17-year-old son Nicolas. He looks listless, he tells fibs, and he’s skipping school. Everywhere he goes he makes a mess. Sometimes he scribbles meaningless doodles on the walls. Clearly he is having some behavioural issues. Is this just teen angst? Or is he mentally ill? Whatever it is, he becomes more and more perplexed. And perplexing. Nicolas’s self-diagnosis is that life is weighing him down, but clinical depression is much more likely. His arms are covered with scars from self-harm.

At first, Nicolas is living with his mother, Anne, but because this doesn’t work out he moves in with his father, Pierre, who has a new partner, Sofia, and a little baby son. Very nice, but these shifts of domesticity don’t seem to help him much. At the heart of this play there is a very bleak vision of what it is like to feel depressed. Misunderstood; misplaced; missed. One has the sense that this is a story about how hard it is to imagine the inner life of your child. In one terrible incident Nicolas finds out what his parents really think about him, and it’s not good news. There’s also a central ambiguity about who exactly is the son in this story: Pierre is also a son and his cold relationship with his father, who continues to influence his life choices, seems to infect his relationship with both Nicolas and his other son, baby Sasha. As Philip Larkin memorably put it, “Man hands on misery to man.”

This is a play about parenting choices, and most of the dramatic tension comes from the realization, which comes to you quite early on, that the grown-ups are all making the wrong decisions. As the story unfolds there’s a ghastly tragic inevitability about events and however hard you might wish for a different outcome — a desire which Zeller plays with in an arresting and heartbreaking epilogue — there is nothing you can do. And there’s something truly terrible about the idea that even if the son is lost, his parents are equally at a loss. Humans stumbling about in the dark forest of life, always too busy to concentrate on what really matters. Tragic indeed.

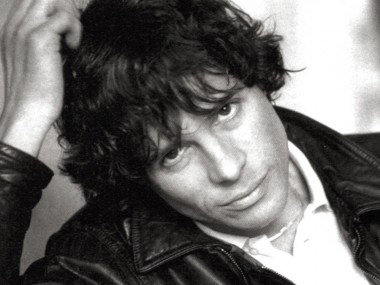

Translated by Christopher Hampton, who is Zeller’s English voice, the story has a great clarity, although it is also frankly melodramatic, especially towards the end. Michael Longhurst’s powerful and operatic production, helped by Lizzie Clachan’s broad beige set, with its broken stag’s head, and accompanied by great blasts of tempestuous music by Isobel Waller-Bridge, runs like clockwork. But it is a dark journey with only a few moments, such as a dazzling dance sequence, to alleviate the gloom. John Light (Pierre) and Amanda Abbington (Anne) start off with worried awkward exchanges, a huge stage distance between them symbolizing their emotional estrangement. Light is fluent, in denial, then angry and dictatorial, while Abbington is brittle, ready to break. Amid their quotidian chat the set suggests mental confusion as it gradually fills up with mess. By contrast, Sofia (Amaka Okafor) is more maternally homely and Laurie Kynaston (Nicolas) gives a great and nuanced performance as the bewildered teen. Gripping stuff. Together they create a tense psychological thriller as bleak as it is strong.

This review first appeared on The Arts Desk