The Vertical Hour, Royal Court

Tuesday 22nd January 2008

Just as the Iraq War has slowly slid off the front pages, British theatre comes up with a superb play about the subject — and they say that playwrights have their fingers on the pulse! Actually, they seem to be running late. To be fair, David Hare’s The Vertical Hour first premiered on Broadway in 2006, when the topic was still very hot. And, to be even more fair, it’s about a lot more than just politics.

Nadia, the central character, is an experienced American war reporter: you know the kind of thing — she’s been in the Balkans and the Middle East. Classic war zones. Now, however, she has swapped career and instead teaches on some prestigious international relations programme at Yale University no less. She’s an expert on the politics of military intervention, a policy which she believes is in itself a good thing, and her advice has often been sought by the US President.

But don’t expect to meet any White House people in this drama. It’s Nadia’s private life that powers the play: she is in love with an expat English osteopath called Philip, who takes her with him on trip to back to his roots. To see his father, Oliver, at his home in remotest Shropshire. In this English idyll, Oliver, a talkative and humanistic GP, rules the roost and of course he is against the Iraq War — so soon mighty ideas are clashing as Philip’s father and his girlfriend argue well into the night.

Nadia is very much a classic Hare character: part idealised female, part seriously troubled woman, part a vehicle for ideas. Even as a liberal, her support of the Iraq War is actually perfectly convincing; what is less credible is the way this strong and intelligent woman immediately crumbles when Oliver points out the mess that is post-war Iraq, a place of societal breakdown. As if Nadia couldn’t have worked that one out for herself.

Still, it’s obvious that Nadia and Oliver are never going to agree: if, as she insists, “politics is about the reconciliation of the irreconcilable”, these two need more than politics to bring them together. Hence the importance of Philip. Although he is the most underwritten of the three characters, the drama needs him most. He enables Hare to quit the perfunctory political arena and to move much more confidently into the territory of the personal.

Pretty soon, Hare shows that the relationship between Nadia and Philip is that of a safe but a bit undemanding and a bit passionless couple. The real intensity is that between Philip and his father: the son thinks that Oliver is trying to seduce Nadia, and blames him for the misery of his mother’s marriage. The father thinks that Nadia is just a bit out of his son’s league. Oh well.

This aspect of the play is kind of fascinating, and there is a profound feeling of ambiguity at the heart of the play. There’s also some loose talk about psychoanalysis, and this highlights the way that Hare sees how all of his characters are motivated by both conscious and unconscious desires, and needs. By the end, he thankfully refuses to offer up any neat psychological punchline. Ambiguity persists.

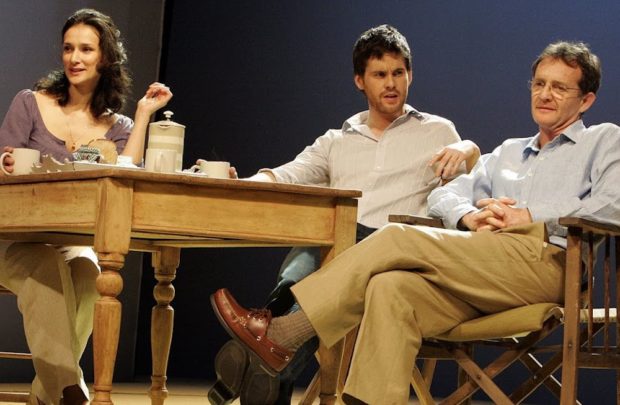

With a superb performance by Indira Varma as Nadia, and a less than charismatic turn by a downbeat Anton Lesser as Oliver, Jeremy Herrin’s rather restrained production doesn’t exactly fly — although it is drenched in some delicious colour (thanks to designer Mike Britton and team). Still, despite this, and Hare’s tendency to verbosity, this is a great play in which the personal and political are wonderfully entangled.

Believe me, if you see this show, you’ll have plenty to discuss when you leave the theatre — and it won’t be Iraq you’ll be talking about. Ten to one, it will be about your life choices.

© Aleks Sierz