The Thrill of It All, Riverside Studios

Tuesday 26th October 2010

It’s pretty hard to describe a Forced Entertainment show. You really have to have been there. But let’s try anyway: imagine a stage full of crazy dancers, the men in black wigs, the women in white ones, prancing around, flinging their arms in the air, mistiming their high kicks, and then running frantically up and down the stage. The lighting slides from bright white to sick pink, and the music is pop tunes with Japanese lyrics. Welcome to a wonderful world of controlled zany exhilaration.

Things go up a gear when one of the dancers starts carrying a red carpet on his shoulders, and soon a ragged chaos ripples across the stage as dancers bump into each other, falling over, ending up in piles of writhing bodies. Then comes a quiet bit, with the women talking into hand-held mikes, their voices distorted into high-pitched squeaks, and the men’s into gruff bass notes. Wowie, it’s a weird party.

This Sheffield-based experimental company majors in two different kinds of show: small ’n’ intimate, and bold ’n’ brash. The Thrill of It All is an example of the second kind. And then some. Described as being “a large cast on a big stage, filled with deranged dancing girls and derelict comedians”, this is big theatre par excellence, and contrasts with the company’s recent small-scale shows, Spectacular and Void Story.

The Thrill of It All is dizzy, it’s poppy and it’s so, so, so silly. The quiet passages, when members of the company take it in turns to talk to the audience, always using an uncanny mix of truth and cliché, are beautifully poised between good ideas and extreme folly. And, as the evening progresses, you can’t fail to be impressed by how well worked out all this chaos is: all the dance moves are both joyful and incompetent, and the accidents are more than fortuitous.

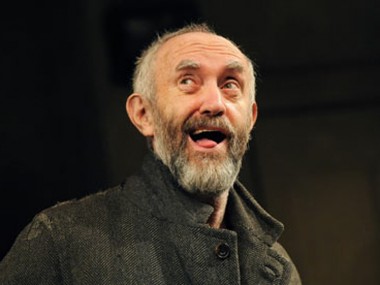

Directed by Tim Etchells, the core company of actors — Robin Arthur, Claire Marshall, Cathy Naden and Terry O’Connor — has been expanded with the addition of five others. All nine actors are on stage all the time, dressed in parody lounge suits and party frocks. In the quieter moment, the girls beam and say positive things about having fun and a good life; the men are more depressed, aggressive, sentimental, useless. Fights break out. As usual, Richard Lowdon gives the show’s design its distinctive look.

As ever with Forced Entertainment, one of the themes is the strangeness of performing, the tensions between practised routines and casual accidents. What do audiences want from performers, and how do performers feel about such demands? Occasionally, there are slightly uncomfortable exchanges when sex is mentioned, or disability, or joblessness. Somehow, these quiet monologues of faux desire, fake confession and unconvincing passion lend the wild dancing a sense of emotional release: the sequins flash brighter, the sweat stains on the tuxedos spread wider and the gestures become more unrestrained.

And finally there is the odd soundscape of the show, which features Japanese lounge music, by 1960s performers such as Kyu Sakamoto (the Tokyo Cliff Richard of his day), as well as an amazing girl duo called The Peanuts. Go on, have a search on YouTube. There’s an appealing energy to the music and it’s also slightly disturbing and dark. Miming along to it, the cast enact fits of pique, vindictive glances and give in to their jealous urges. Yes, Forced Entertainment proves once again that they can take you to some very strange places. It really doesn’t get any better than this.

This review first appeared on The Arts Desk