Total Immediate Collective Imminent Terrestrial Salvation, Royal Court

Wednesday 4th September 2019

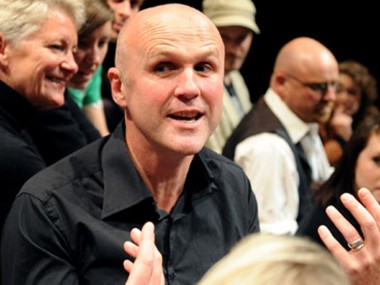

Playwright, theatre-maker and performer Tim Crouch is one of Britain’s most innovative creatives, with a big back catalogue of challenging and stimulating stage work. Typically he tells stories about profound loss, while simultaneously questioning the basis of theatrical representation: how is what we see on stage true? In what way is it real? And how can you tell? His latest, which comes hotfoot from the Edinburgh Festival to London’s Royal Court — in an already much praised production from the National Theatre of Scotland — is, as its title so archly suggests, about a messianic cult. But it is also much more.

As the audience files into this venue’s attic studio space, it is immediately obvious that this will not be an ordinary show. We have to leave all our possessions on a table in one corner, and then take our seats in a circle. We are a congregation. On each chair is a dark green hardbound book, whose contents look like a mixture of religious fantasy and graphic novel. To believers, this book is real: it tells the future, it is prophesy. It is also an amazing text, an effect enhanced by Rachana Jadhav’s pencilled illustrations and the barely suppressed delirium of some of the words (the rest are stage directions and dialogue). Before the show even begins (whatever that means), we are already participating — just by peeking at the words of a contemporary messiah.

This book is vital: Sol, an 18-year-old, is certain that it foretells the future. She lives in South America with Miles, who is her father and the leader of a new apocalyptic cult which believes that the next solar eclipse signals the end of the world (sort of). As we sit in the circle, her mother Anna explains that she is travelling to rescue her daughter from this religious community and tells us that we must follow the story by reading the green book together. Collectively. It does, after all, predict what is going to happen. So, whenever Anna gives us the signal we turn another page. Oh, and in the background of this family’s story is a devastating personal loss.

By following the 70 minutes of action through the words and pictures in the book, reading extracts and dialogues together with the actors, the audience is not only participating in the creation of a theatrical event, it is also exposing one of the central illusions of text-based theatre: that the show must follow the words on the page, the same words spoken by the same character on every successive night. The text determines the show. If Miles’s cult is all about predestination, then so is the act of theatre. But does it have to be like that? What if the actors change the text? What if the audience varies?

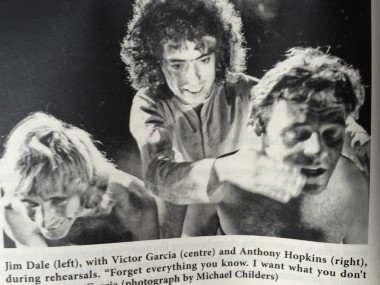

So Total Immediate Collective Imminent Terrestrial Salvation is not only a show that nods to historic cults — such as Jim Jones’s suicidal People’s Temple in Jonestown, Guyana, which killed more than 900 people in 1978 — but also examines the notion of free will. Can extreme acts, it seems to be asking, expiate past tragedies (which cannot be changed, are irreversible and irredeemable)? If there seems to be no limit to what human beings can believe, then what does this do to our sense of reality? Together, in the theatre, we can examine these ideas, which pulsate in the background of Crouch’s text, which is partly a sci-fi fantasy and partly a sociology of religious belief.

There is also something very subtle about this absorbing experience. Our attention is divided, sometimes more or less equally, between reading words, looking at pictures, watching actors and being speaking participants. Despite this, we all seem to be able to absorb both the tragic backstory (death of a child) and the tense confrontation of Anna and Sol, mother and daughter, sceptic and believer, reason and irrationality (the cult is pretty dictatorial). The show dazzlingly reaffirms that theatre takes place inside the heads of audience members, and that our actual participation can be a source of both comedy and wonder (different bodies, different voices, different people all contribute).

Crouch’s text plays a clever game with all these ideas, and his performance as Miles is laid back and low key, offering the gentle charisma of a guru’s confident soft control. Likewise, Susan Vidler’s Anna is a quietly spoken guide to the story, only occasionally allowing the ravages of a hurt and guilt-stricken mother to show through. Best of all is newcomer Shyvonne Ahmmad’s Sol, whose gleaming eyes and facial grimaces convey the guileless thoughts and irrational bewilderment of the true believer. As directed by long-term Crouch collaborators Karl James and Andy Smith, with Pippa Murphy’s soundscapes (which reproduce the calm of nature and the rush of cosmic storms), this is a brilliant meta-theatrical experiment. It is touched not by God, but by sheer theatrical genius.

This review first appeared on The Arts Desk