Truth and Reconciliation, Royal Court

Monday 5th September 2011

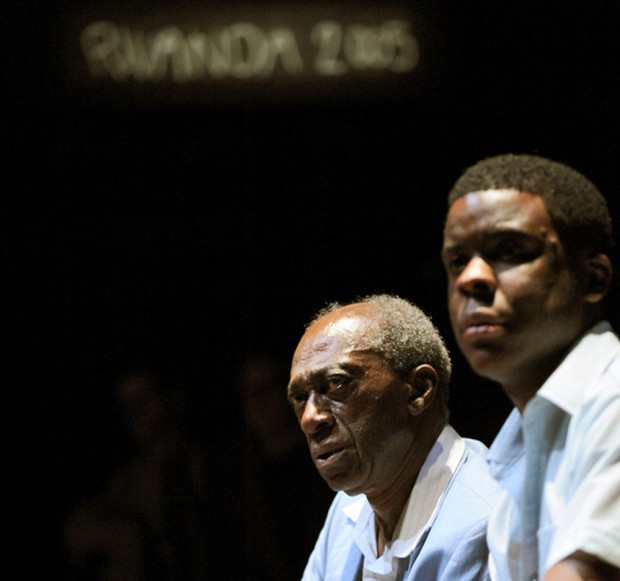

Can an ordinary wooden chair be an instrument of torture? Of course, every brute investigation makes use of such furniture, whether as a place to tie the victim down, or as a weapon to attack them with. But, as debbie tucker green’s new play so eloquently shows, the wooden chair can also be a more subtle and unexpected instrument of fraught emotion: at every meeting of a truth and reconciliation commission, the wooden chair is there in the hall, itself a dumb witness to the clash of old enemies.

Dealing as it does with the horrors of genocide, war and violent conflict, Truth and Reconciliation is a mercifully short play, just 65 minutes, but it has an epic sweep, taking in the injustices of South Africa under apartheid, the Rwandan genocide, the mass rapes of Muslims in Bosnia, the struggles of Zimbabwe and the Troubles of Northern Ireland. Unlike her previous play, Random (televised on Channel 4 last month), with its cast of one, this time Green has a company of 22 actors.

And instead of writing a straight political drama, Green does something which proves just how inventive and imaginative a playwright she is. She focuses for the most part on the small and incidental emotions: a woman’s family ask her to take a seat, but she stubbornly stays on her feet; two guilty men talk about giving up smoking; nervous witnesses chat about the drive to the hearing, or grumble about having to wait to be heard. A husband asks his wife not to testify. Then the big set pieces suddenly arrive: a victim’s widow confronts her husband’s killer; the ghosts of long-dead victims torment their murderers.

Written with all of Green’s uniquely insistent and reiterative pulse, this is a play of small gestures that gradually blossom into big statements. At first, it is all about a cushion for a hard seat, an offered cigarette, a touch of recrimination. Nerves, questions, uncertainty, anxiety. A litany of anti-heroism. Then this develops over the course of a mere hour into examples of quiet courage, brave confrontation and the clash between the lust for revenge and the unending promptings of conscience.

Designer Lisa Marie Hall, who also worked on green’s television adaptation of Random, has turned the theatre into a dark cavern with punishing wooden seats for both audience and cast. Across the black floor, there are muddy footprints, as livid as bruises, and the names of victims appear everywhere: on walls, on seats, on the stairs. Behind this dark atmosphere of fear and loss, you can hear the sounds of voices chanting and hands clapping. As directed by green herself, the play has outstanding performances from the whole cast, only a few of whom I have room to mention: Wunmi Mosaku, Pamela Nomvete and Susan Wokoma bring dignity to their speeches of defiance; Clare Cathcart spits fire as an Irish irreconcilable; and Aleksandar Mikic and Izabella Urbanowicz bring alive the pains of Bosnia.

During this show, I slowly became aware that my body was showing signs of nervous tension: sweaty palms, dry throat and a tight stomach. Even though the terrors of conflict are obliquely referred to, the reality of a world of pain, the infinity of loss and the courage of determination all come across loud and clear. The writing delicately explores the balance between the desire to know what happened to the disappeared, the need to bear witness and the difficult acceptance of truth. Finally, this moving play asks but doesn’t answer (how could it?) the terrible question: how much horror can we live with?

This review first appeared on The Arts Desk